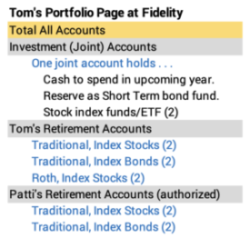

In Nest Egg Care (NEC) I recommend two bond funds for your retirement portfolio. One for US Total Bonds (Patti and I own IUSB; you have a number of options.) and one for International Total Bonds (Patti and I own BNDX the ETF of the index fund VTABX; I still think that is about the only option). The purpose of this post is to look at US bond funds that are options to IUSB – iShares Core Total USD Bond Market ETF. IUSB is still at the top of my list of funds, but you might want to consider alternatives.

== Bonds are INSURANCE against DEVASTATION ===

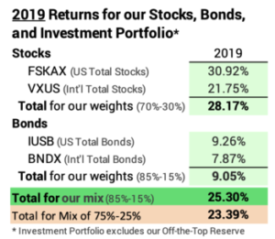

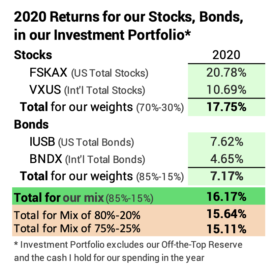

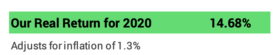

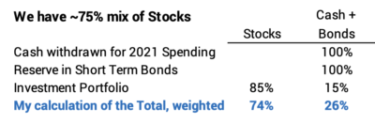

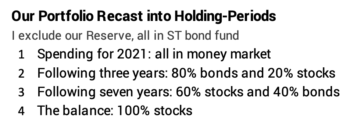

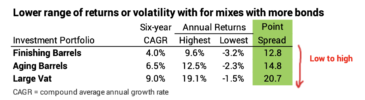

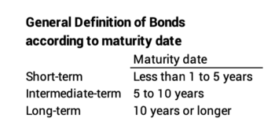

We retirees – in the invest and spend phase of life – are selling securities for our spending each year. All of us should have a mix of stocks and bonds. Stock returns have been greater than bond returns in all but one of the last ten or so years. We are disproportionately selling stocks in those years to get the cash we need for our spending and then to rebalance to our design mix of stocks vs. bonds.

This pattern has repeated: we sell a lot of something that has done well and seems to be on track to do well – stocks – and we don’t sell much of something that hasn’t done as well and likely won’t do as well – bonds. Heck, in three of the last six years I’ve solely sold stocks to get the cash we will spend in an upcoming year, and then I sold more stocks to buy bonds to correctly rebalance. That seems very crazy, but that’s how rebalancing can work. Bonds can seem to be a heavy weight we are dragging along.

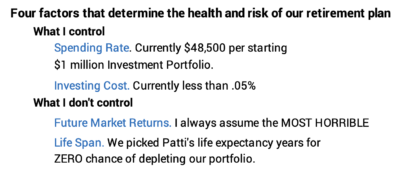

But we retirees can’t lose sight of why we hold bonds. We cannot forget how a year or two of HORRIBLE stock returns can DEVASTATE our portfolio. The odds are high that we’ll experience at least one really horrible year during our retirement. (See Chapter 7, NEC.)

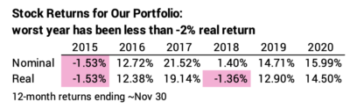

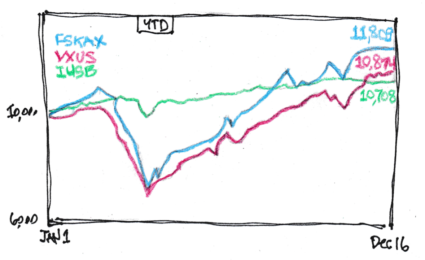

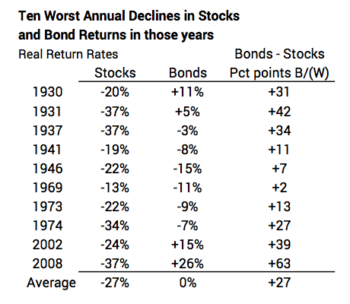

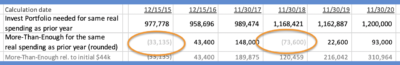

We need to remember what HORRIBLE can look like. This chart from this post shows the periods of the most HORRIBLE stock returns. Here’s a snapshot:

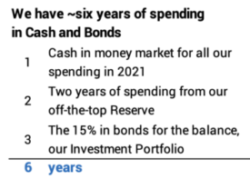

Bonds are insurance against DEVASTATION when stocks crater. When we are hit with HORRIBLE returns for stocks, we sell LOTS of bonds our spending. If returns are really HORRIBLE, we use our Reserve (Chapter 7 NEC) and sell NO stocks. We sell bonds for our spending to buy time for stocks to recover.

== Criteria for our Insurance ==

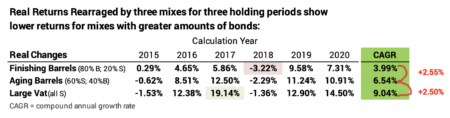

The key criterion for insurance is that we want it to be there when we REALLY want it. Bonds are good insurance because their returns down follow the exact same pattern of the ups and downs of stocks. Stocks usually outperform bonds, but bonds outperform stocks when they crater.

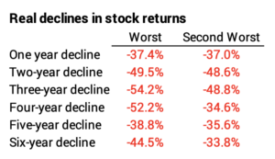

The benefit of bonds is most clear in the years of MOST HORRIBLE returns for stocks. In the ten worst years for stocks, bonds averaged 27 percentage points greater return. 27 PERCENTAGE POINTS! Bonds have “been there for us” in each of those years, especially for the very worst ones.

== What to pick? ==

I think your buying decision for your bond insurance is similar to your buying decision for car insurance. Do you want GEICO, Allstate or Progressive? You may find some differences, but you know your choice will there when you need them. I think any choice of a diversified mix of bonds is going to have the same effect: their return will be MUCH BETTER in a year or years when stocks crater.

You have excellent alternatives for your bond insurance. I picked IUSB – iShares Core Total USD Bond Market ETF – in December 2014 and I won’t change that choice.

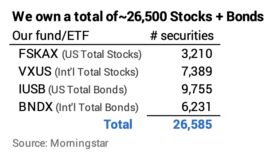

Why did I pick IUSB? I favored a Total US Bond fund (See Chapter 11, NEC). I like a total bond fund because it is the ultimate of diversification. With the two bond funds that we own, I can say, “Patti and I own almost every bond traded in the world. We’re not betting on a specific type or maturity of bond. We have the ultimate in diversification.” (I can say the same for our two stock funds.)

An article in Morningstar described IUSB as having a shade higher credit risk in its portfolio than other total bond funds; its credit profile was similar to portfolios of actively managed funds; it would outperform other total bond funds; and almost NO actively managed bond funds had better return.

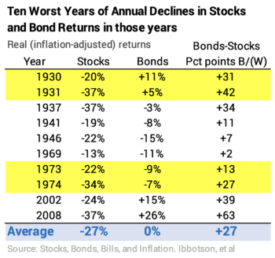

Because of its mix of short, intermediate, and long-term bonds, the average maturity of all of IUSB’s bonds – ~6 years – falls into the Morningstar classification as intermediate bond.

Morningstar now describes IUSB as “Intermediate Core – Plus.” As I read this article, Core means no more than 5% of holdings are less than investment grade, while Core-Plus is no more than 8%. That seems like a small difference to me, but apparently that spells the return advantage.

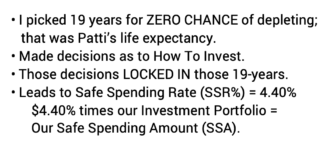

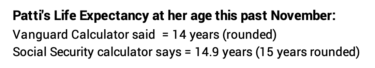

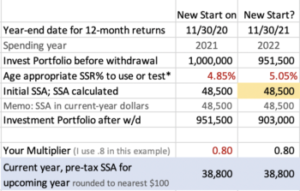

The Retirement Withdrawal Calculator we should use, FIRECalc, uses Long Bond as its default for fixed income. I replaced Long Bond with intermediate bond (“5 Year Treasury” is close enough) and got the exact same Safe Spending Rate (SSR%).

== Some good alternatives for Total US Bond ==

This recent Morningstar article , “The Best Bond ETFs,” has a good list. On this chart, Choices for Bond Fund, I focus on ones similar to IUSB, and I added a few I found on this site. Three are Core-Plus, four are Core, and three are intermediate-term corporate bond funds. Three are long-term bond index funds/ETFs.

Here are my highlights:

• FBND – Fidelity Total Bond ETF – was just two months old when I was first making decisions for our plan December 2014. FBND is actively managed with a higher expense ratio than IUSB, but it has returned about one percentage point more per year than IUSB over the last three to five years.

• The largest US total bond market ETF is AGG – iShares US Aggregate Bond ETF. BND – Vanguard Total Bond Market EFT – is also large. The crowd likes these two.

• You can narrow in on corporate bonds. This choice will also have no effect on the Safe Spending Rate (SSR%) you get from FIRECalc. The three corporate intermediate bond ETFs all have higher returns in the past years than my more diversified IUSB.

• I display four choices for long-term bonds, all index funds. I think BLV – Vanguard Long Term Bond ETF is closest to the default choice for fixed income in FIRECalc. All four have had greater historical returns than any of the intermediate-term bond funds, but price will be more sensitive to changes in interest rates.

Bond prices move in the opposite direction to interest rates. An increase in interest rates means lower bond prices: the bond is less valuable for the stated dollars of interest that it pays. Interest rates are as low as they’ve been in our lifetimes. They can’t go lower. (I think I’ve said that to myself four years in a row now!) They can only go higher. That means greater chances that bond prices will fall. Rates have increased slightly this year, and long-term bonds have declined more year-to-date than intermediate-term bonds.

Conclusion: We retirees own bonds as insurance against devastation of our portfolio from HORRIBLE stock returns. We pull out our insurance policy and disproportionately – and maybe solely – sell bonds for our spending when stocks crater. History tells us bonds have been very good insurance in the ten worst years of stock returns. I think almost any widely diversified bond fund or ETF is fine for your retirement portfolio. I like a total bond fund, which is the ultimate in diversification. This post displayed alternatives to the one I rely on – IUSB – iShares Core Total USD Bond Market ETF.