Reader Steven asked me in an email if I had looked at or considered Closed-end Funds (CEFs) for my retirement portfolio. I did not, and I haven’t looked at closed-end mutual funds in years. I found an article that listed the “Ten Best CEFs for 2021”; I use them as examples in this post. I conclude in this post that I would NOT consider Closed-end Funds for our retirement portfolio. I’ll stick with more boring – and more predictably better performing – total market index funds.

== What is a Closed-end Fund? ==

A Closed-end Fund raises initial capital like a new public company and thereafter its shares trade like a stock. No new money flows into the fund when an investor buys shares; no money flows out of the fund when an investor sells his shares. Depending on its organizing documents, these funds have an ability to borrow money to be able to invest more, invest in illiquid securities, and sell shares short – an investment that makes money when share price falls. The swash-buckling fund managers can swing for homeruns.

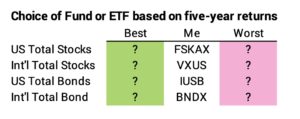

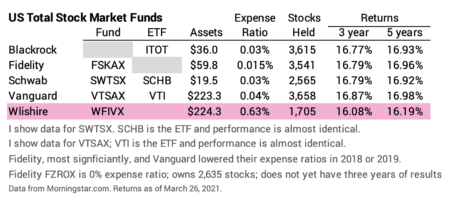

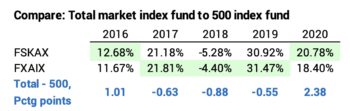

A traditional Open-end Fund trades at its end-of-day net asset value per share: new money flows into the fund when an investor buys new shares, and money flows out of the fund when an investor sells or redeems shares. Patti and I own FSKAX, a traditional Open-end Fund. FSKAX invests its assets in shares of publicly-traded companies; FSKAX owns shares in more than 3,500 companies. It does not borrow or sell shares short.

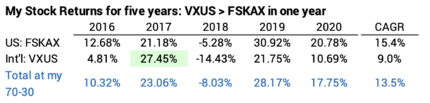

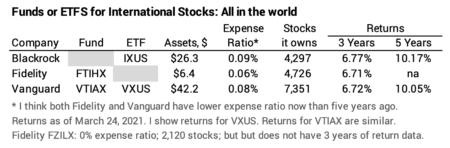

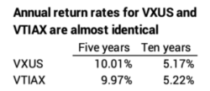

An Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) is a variation or hybrid of an Open-end Fund in that shares trade during the day like shares of companies. Patti and I own VXUS, which is the ETF for its sister fund, VTIAX.

I view an ETF as the same as a traditional open-ended fund although one can debate the small pluses and minuses of the two. The annual change in net asset value of VXUS basically is the same as VTIAX, and the price of VXUS tracks its net asset value over time. Over time the total return for VXUS – based on its price – closely tracks with the total return for VTIAX based on its growth in net asset value.

Why did I buy VXUS and not VTIAX? Our investment accounts are at Fidelity. VTIAX is not part of Fidelity’s network of no-transaction-fee funds. The transaction fee to buy VTIAX and other Vanguard funds is $75. It’s no fee now to buy VXUS. (I think it was $7.50 when I first purchased VXUS.) I hold VXUS in several accounts – Patti’s IRA and my IRA, for example; and I could be making annual purchases when I rebalance. I wanted to avoid the $75 fees.

== You want to focus on Total Return ==

The article I cited focuses on a higher payout to investors from CEFs than from a traditional mutual fund, but that that difference has no meaning to me: I want to compare total returns. Total return for a stock is the calculation of increase in value from change in price + dividends reinvested on the day they are issued.

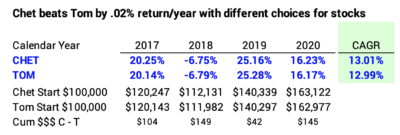

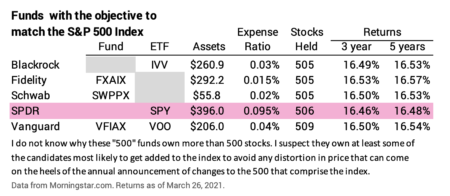

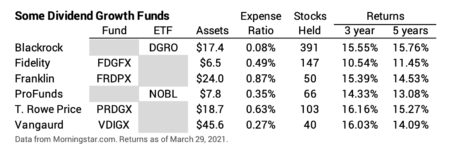

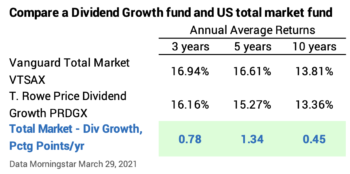

How might these CEFs perform over time? We need to compare them to peer index funds, funds that very closely match what the market delivers to all investors because their investing cost – expense ratio – is so low.

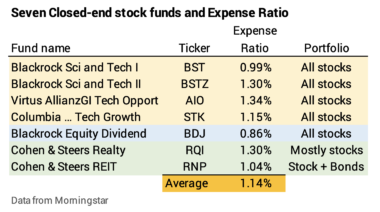

The difference in expense ratio gives us a good indication of how these CEFs might do in the future. The seven stock funds listed have an average expense ratio of ~1.15%. Patti and I pay .015% for FSKAX – about 1/75th.

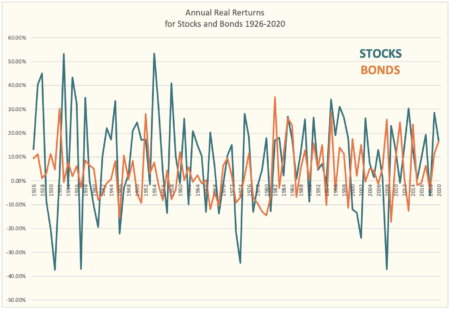

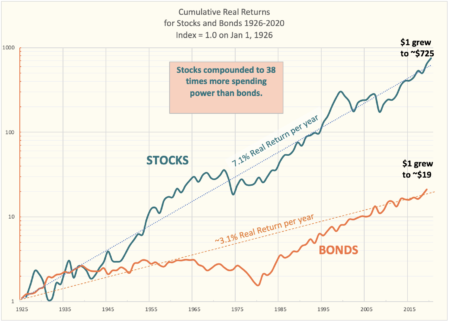

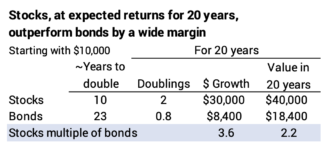

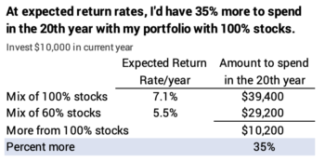

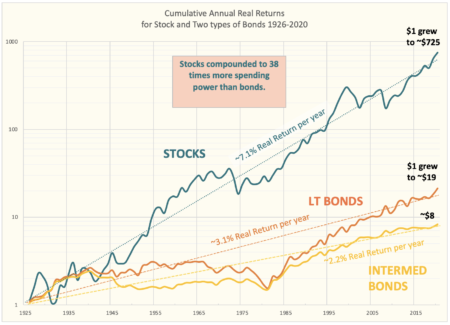

Expected real returns for stocks are 7.1% per year. The penalty of ~1.15 percentage points is a big hurdle to jump over: it’s draining 16% of future growth (1.15%/7.1%). The fund manager has to beat other actively managed funds by about 20% just to match the results of a peer index fund (1/(1-16%)). That’s a tough, tough task. A bet on one of these funds increases your chances of under-performance, and you don’t want to do that for your retirement portfolio.

== Only one of seven is a broad-based stock fund ==

Only one of the seven stock funds is a general stock fund. Two are real estate funds and four are technology funds.

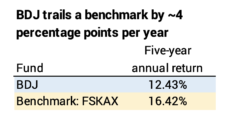

The general stock fund trails FSKAX, as an example, by FOUR percentage points per year over the past five years. UGH. I’m not sure how this performance tracks to a Top Ten rating.

== Narrowly focused funds ==

I don’t see any reason to suspect that funds with a narrow focus, such as real estate or technology, will outperform in the future. I have no desire to own more of those stocks than I already do.

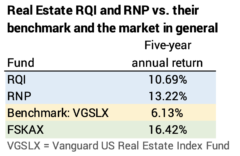

The two funds that focus on real estate stocks have outperformed a peer index fund by more than four percentage points per year; the fund managers beat other fund managers to more than overcome their cost hurdle. But returns for the two trail the general market by three percentage points per year.

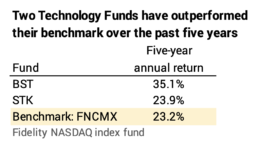

Large Cap Growth stocks have been the highest performing sector the last few years. I can only compare two funds, since two of the funds are less than two years old. The two have performed better than a peer index fund over the past five years. BST has dazzled. Sizzled. It’s in the top one percentile of technology funds over five years (and at the very bottom – 100th percentile – year to date!). Maybe it’s a good bet, but it would be a bet. We have no assurance that these funds will outperform in the future; the evidence tells us that we can’t predict future results based on the past.

== Three bond funds. Sorta. ==

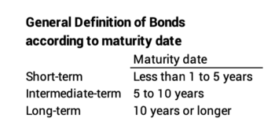

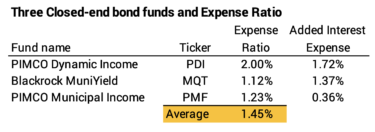

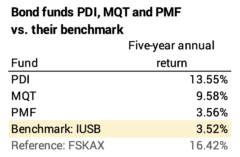

Three funds focus on bonds. They also have high expense ratio, about 25 times the .06% Patti and I pay for our IUSB.

Two borrow significantly to leverage the amount they invest. If those two earn more from their investments than the interest cost, they magnify returns. If they don’t, the leverage will magnify downturns. The two that borrow the most have beaten their benchmark by a wide margin.

I’m not swayed to consider these two:

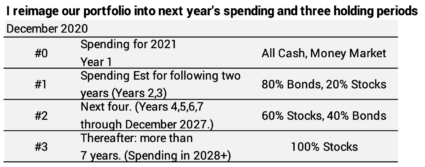

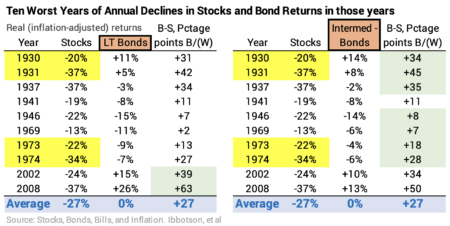

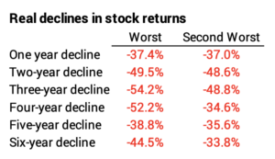

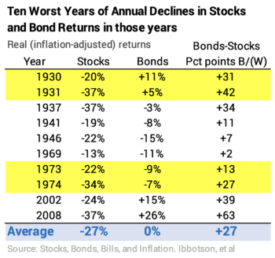

• Bonds are my insurance against steep downturns in stocks. If stocks have cratered at the time I need to sell for our spending, I’ll want to sell bonds – mostly or solely – for our spending. I want bonds to be stable or decline far less than stocks.

• These two behave more like stock funds than bond funds in downturns. Morningstar displays a performance graph for each fund. PDI declined by 30% last February and March. That’s about five times greater than the 6% decline for IUSB. Both recovered, but that performance does not give me much confidence in PDI’s value as insurance against steep stock declines. I would not invest in PDI or MQT as a bond fund.

Conclusion: I looked at ten Closed-end funds in this post: seven stock funds and three bond funds. The one general stock fund underperforms by four percentage points per year. The returns on narrowly focused funds – real estate and technology – are mixed. The bond funds employ leverage to boost returns and appear to behave more like stock funds. They declined almost as steeply as stocks in the steep decline in Feb-March 2020. They aren’t providing the value I’d want when I would want to sell bonds, not stocks, for our spending.