Why do financial advisors structure portfolios that are overly complex?

Posted on January 15, 2021

If you look at a portfolio structured by a financial advisor, it will have MANY different securities. For example, Patti and I own one security for US Total Stocks (FSKAX), but most financial advisors will have at least six securities for US stocks. Why is this? Is there some advantage to holding separate segments of the market that basically add to the whole rather than just owning whole? The purpose of this post it to suggest that an investor gains NOTHING by holding individual segments rather than the whole of the US Total Stock market.

== You already own it all ==

You already own the segments of the market when you own a Total Market fund like FSKAX. Morningstar has a feature called X-ray that its Premium members can use. The X-ray looks at the detailed holdings of a fund or group of funds to tell you what percentage you own of each of the boxes in a style box. Morningstar defines the parameters of each box. Here is its breakdown for FSKAX.

The style box for VTSAX, VTI, ITOT and other US Total Stock Market funds/ETFs would be identical: they all own the same ~3,500 stocks in proportion to their market value to the total market value of all stocks.

The X-Ray tells you that 72% of the value of FSKAX is Large Cap Stocks: 15% + 30% + 27%; that’s in line for the rough estimate of the value of the S&P 500 stocks as a percentage of the total value of all US stocks. The box says 29% is smaller company stocks: 20% is Mid-Cap and 9% is Small-Cap. (The boxes don’t add to 100% due to rounding.)

The box tells you that 34% of the value of FSKAX is Growth Stocks and 25% are Value stocks and the balance is in stocks that fall between the parameters Morningstar uses for Value or Growth.

== Example of a more complex portfolio ==

A number of years ago Patti’s brother put stock options in his privately-held company into a generation skipping Trust. The money in that Trust will not be in his estate at death; he’s by-passed estate tax on the amount in the Trust at his death. The ultimate value of the Trust flows to grandchildren (children of his three children). None of his children have children yet, and, assuming they will, the life of the Trust ends MANY decades from now. I volunteered to be Trustee. (Clearly this Trust will outlive me as Trustee.)

There was no money in the Trust – just stock options – for a number of years, so I had nothing to do. No tax return. Nothing. Then the company was purchased in 2012, and the stock options turned into REAL MONEY that had to be invested.

As Trustee of REAL MONEY, I got serious. I wanted advice on investing and some liability protection as to how the money was invested. I interview several firms and hired a local firm as the Trust’s investment advisor. Mike heads the firm: good guy. Mike suggested a portfolio developed by a king of asset allocation, now a part of Morningstar. The document I reviewed in 2012 stated that the model should outperform the market by two percentage points per year.

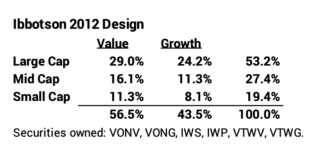

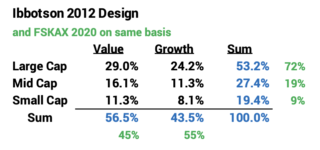

The total portfolio was 14 securities that covered US and International stocks and bonds. Quite an array. I show the portfolio design of six securities for the portion that was US stocks. The portfolio was all in low cost, passively managed ETFs with less than .2% total Expense Ratio, and Mike agreed to a REALLY LOW advisor fee. The total costs for the Trust are very low. I like that.

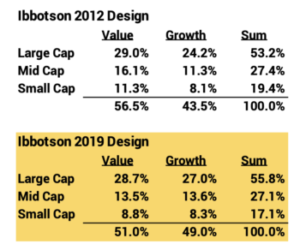

In 2012 I didn’t know about the Morningstar X-ray and how US stocks in total would fall into a style box. It took me some time to figure out what this splitting apart of the total was all about. The portfolio design was saying that it would outperform by 1) heavily over-weighting smaller company stocks and 2) heavily over-weighting value stocks. Compared to the current weights for FSKAX above, this portfolio was double-weighting the Smallest-Cap stocks, overweighting Mid-Cap by about 1.5X and underweighting Large Cap by about 30%. It flipped the weighting of Value with Growth.

== It has under-performed ==

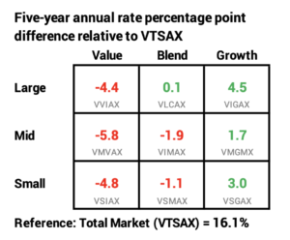

The chart below is from my recent post. Over the past five years, the model’s over-weights have been EXACTLY WRONG. Value lagged Growth by roughly eight percentage points per year. Smallest company stocks lagged Large-Cap stocks by more than one percentage point per year.

I could construct how much the Trust should have now if I didn’t follow the model, but that would just depress me. I don’t want to do that. I’ll just leave it that the overweighting that I bought into was COSTLY.

== It makes no sense to me ==

As I learned more, I concluded that overweighting suggested by the PhD experts made no sense. You definitely don’t want to over-weight smaller company stocks: I find no logical basis or evidence of smaller company stocks outperforming over the past 40 years. I don’t have the same kind of data to explore the logic of why some recommend over-weighting Value, but clearly the recent evidence says that’s not a strategy to outperform.

== The model is more balanced now ==

The Morningstar model changed over time, and the 2019 allocation of the six segments shifted much more to Growth but still favors Value. It shifted more to Large Cap but still favors smaller company stocks. The results for 2020 say the model choices in 2019 were again on the exact wrong track! You guessed it: I’m not going to calculate how much more I would have had.

== Does splitting and rebalancing increase returns? ==

I asked Mike, “I notice the model’s allocation between Value and Growth is almost 50-50. What’s the advantage to holding 51% Value and 49% Growth and then rebalancing to that same 51-49 at the end of each year?” “Because you are always selling high and buying low. You’ll do better over time.”

This sounded logical, but I wasn’t sure. “Do you know of any studies that explain why this works?” “No.” Hmmm. I wanted to dig into this. I did not like the thought of the Trust paying tax just to rebalance. Trusts pay taxes at the highest marginal tax rate – 20% on all long-term capital gains, for example; 37% on short-term gains. The Trust is giving up some potential growth if it pays taxes earlier than it otherwise could.

Here’s my analysis: ignoring tax effects, the rebalancing argument does not hold water. Plug in tax effects, and the argument sinks like a rock.

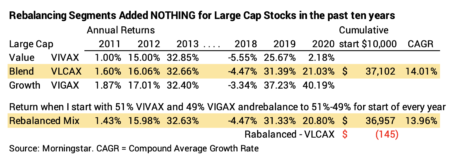

The example here is for Large Cap stocks, but the result would have been the same had I picked Mid-Cap or Small-Cap. In this example, I start with a total of $10,000 ten years ago. I start with a mix of 51% for Value (VIVAX) and 49% for Growth (VIGAX). At the end of the year I rebalance to 51-49. Result: at the end of ten years I have less from the effort to rebalance back to 51-49 than if I had just held the fund that’s a blend (VLCAX). Rebalancing would look worse if I figured out this out on an after-tax basis.

== So why do they put you into six? Or more. ==

Cynical Tom thinks the added complexity just means financial advisors make more money. It’s about the optics: you think they are earning the amount you are paying them. (And you really haven’t translated the amount you pay to the amount of growth you are giving up over time: the added ~1% cost that you pay deducted from ~6% expected, real annual growth before the added cost = 15% less for you. Per year.) Why do folks pay?

• Six looks a lot more sophisticated than one. Your retirement financial plan is very important. The story is that it’s complex task to assemble a portfolio. You deserve the most precise, sophisticated plan our PhDs have developed. Talented PhDs and portfolio designs like this were only in the reach of the mega-rich years ago. A plan with lots of moving parts and a beautiful pie chart showing a bunch of slices supports this story. Our brains question a portfolio with just a few moving parts.

• You advisor and company can find data, if they stretch back to more than 40 years ago, that indicates that smaller company stocks will outperform. They can cite data and studies that say value will outperform growth. Overweighting in those two directions sounds like the very smart thing to do. Everyone wants to beat the market and these experts are telling you they can. You want to believe this. It’s a story that’s hard to resist.

• The rebalancing argument – always sell the high one to buy more of the low one – sounds perfectly logical. Obvious almost. All that rebalancing for the moving parts takes time and effort every year that you don’t want to spend. It’s worth paying your advisor and his firm to do this for you.

Conclusions: Financial advisors construct portfolios that are far more complex than they should be. I think they do this because it makes them look smart, talented, and hard working. The evidence suggests that their cost and the added complexity of your portfolio merely results in lower returns for you; that’s the same as more money for them. The optics and arguments for complexity are powerful. Don’t buy into them.