A financial plan has to consider two aspects: 1) How Much Do You Plan to Spend from Your Portfolio Year-By-Year and 2) How Do You Invest. Those two pieces of the puzzle have to fit together. You can’t judge one without the other. But if you took your plan to a financial pro (or asked him/her to start on a plan), he or she would almost certainly only consider the second puzzle piece, “How To Invest,” in officially judging if you were “Conservative” or “Aggressive”. A plan that I think is (ultra) Conservative will be judged as (ultra) Aggressive. This makes no sense to me.

Here’s my story.

My brother-in-law and his wife created a Trust about 10 years ago. I agreed to be Trustee. The Trust held option shares in his privately held company and almost no cash to invest. There wasn’t much for a Trustee to do.

They chose to create a Trust primarily to avoid future estate taxes. Maybe those shares would be worth a lot in the future. The Trust will pay for educational expenses for their children and for potential extraordinary health-related costs. But the primary beneficiaries of the Trust are grandchildren – not yet born when the Trust was formed. The Trust legally exists until the death of the last child to die. That’s perhaps 70 years in the future. That’s a really long investment horizon.

My brother-in-law’s company was sold about five years ago, and the option shares turned into REAL CASH to invest. Oops, all of a sudden, I had real work to do. I had to get that invested correctly.

I consulted with a lawyer, and I decided that I needed to hire a financial advisor, even though I thought the investment decisions were not complex. It was a CYA action to avoid any potential liability of being both Trustee and Investment Advisor to the Trust. And I needed someone to carry forward if something happened to me. (Don’t think I’ll be around for 70 more years!)

I found Mike, a very good guy and financial advisor with lots of professional initials after his name. I liked his firm and the other folks there. Mike agreed with me on investment structure for the Trust and agreed to a very reasonable fee; he knew the Trust would be a very long-term customer.

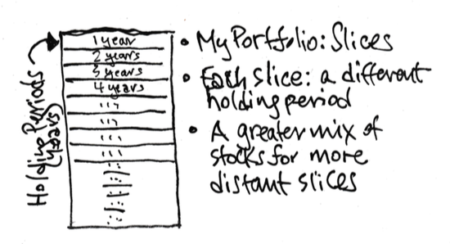

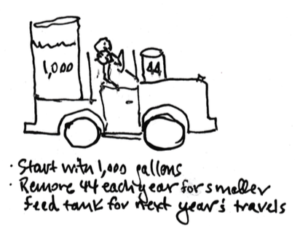

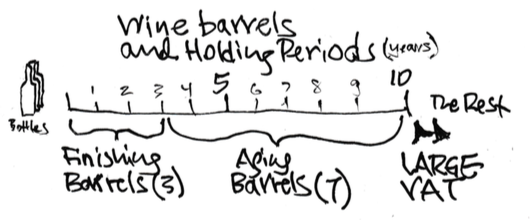

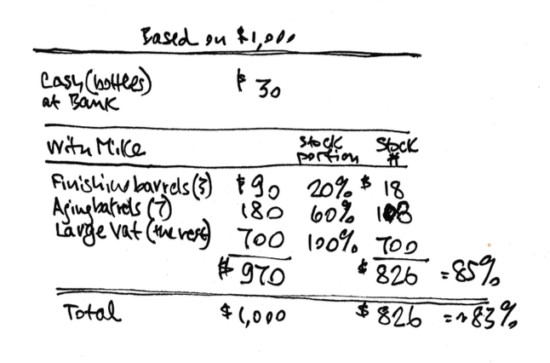

I first developed a cash flow plan that forecast year-by-year cash needs that I then put into four groups. I was somewhat conservative in my estimate of cash needs, overestimating how much I would actually need to spend each year (primarily taxes and distributions for educational expenses). I grouped my years of cash flow needs. Some people might call these groups “buckets.” I chose to use the analogy of “wine bottles and barrels” instead. Here’s the arrangement of the bottles and barrels.

Bottles: wine that is bottled from the finishing barrels each December. It’s the cash the Trust will spend in the upcoming year.

Finishing barrels (3) hold three-years of cash needs – holding periods of one through three years. (A holding period is the length of time you hold onto an investment before you sell it for spending.)

Aging barrels (7) hold cash needs for seven years – holding periods of four through ten years.

A Large Vat holds the remainder. The first drop of wine from the Vat would be consumed not before ten years.

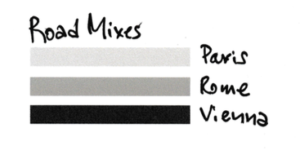

Mike and I both agreed that the following made perfect sense in terms of investment structure. We both agreed that this was a conservative plan plan given the holding periods for the barrels.

• Bottles: cash in the Trust’s checking account

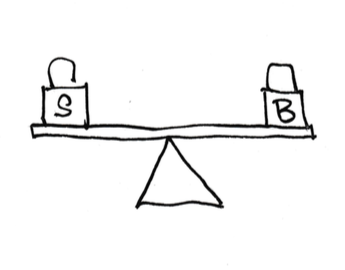

• Finishing barrels in one account with Mike at 80% Bonds and 20% Stocks

• Aging barrels in one account with Mike at 40% Bonds and 60% Stocks

• Large Vat in one account with Mike at 100% Stocks

I next multiplied my cash forecast by the mixes for each group of wine barrels. That total multiplication added up to 85% Stocks and 15% Bonds in the accounts with Mike. Made perfect sense.

Mike and I met to sign the final paperwork to set up the account. He had one required form for me to sign that asked two questions as best as I remember:

1. What would you do if stock returns were below 0% next year? This was a multiple-choice question with answers ranging from Sell All Stocks to Do Nothing.

Of course I marked “Do Nothing.” I knew real stock returns have been below 0% about one-third of all years, so this this seemed like a strange question to me. My average holding period for the total invested is probably 30 years. It’s 100% probable that stocks will outperform bonds over that period, so I’d be foolish to sell Stocks if the return falls below 0% for one year. That seemed like a really silly question to me.

2. I then had to mark how I classified myself as an investor. The choices ranged from Conservative to Aggressive. I marked Conservative. (As Trustee, I’d be crazy to mark anything else.)

Mike said, “You can’t mark that box.”

“But, Mike, we’ve been all through this. My cash needs are really low relative to the amount of money that is there. I’ve probably overestimated my cash needs. Heck, I don’t even think I withdraw the dividends that will be earned in any year. This pool of money can only grow over time; it will never run out. I’m being conservative to overly conservative in the way I’ve forecasted cash flows and the way we’ve structured the three accounts. Don’t you agree?”

“Yep, I agree, but you have to put your checkmark in the Aggressive box. (I think he would have said Wildly Aggressive if that existed.) My compliance officer and the regulators would not permit me to have you invested in 85% stocks if you don’t check the Aggressive box.”

So, I erased my checkmark and placed it in the Aggressive box. It made no sense to me.

If I had not thought it through, I would have simply checked the Conservative box and just taken the advice from the pro. With an advisor other than Mike, I might have been convinced that 85% stocks was too Aggressive and Risky, exposing me to undesireable liability. I would have (incorrectly) lowered the mix of stocks significantly.

Why is this? The label financial folks are geared to judge a portfolio is in relation to one-year variability of returns, and for one-year periods stock return rates are more variable than for bonds (but the opposite is true for long holding periods). If I bought into that thinking, I would wind up with an investment mix that made no sense for the Trust’s long, long time horizon.

Conclusion: When we’re retired our financial plan has similar components to this story.

We have a long investment horizon. We clearly don’t have 70 years, but we typically are planning for a retirement period that may last decades.

We have different investment horizons or holding periods for when we will actually sell securities from our portfolio to get cash to spend. Those holding periods will range from one year to maybe 20 years or more.

Our investment piece of the puzzle is related to our spending rate piece of the puzzle. For example, a lower spending rate means a greater portion of stocks will be in the Large Vat. That’s going to work out to a greater overall portion of stocks.

When you use Nest Egg Care to make your decisions for your financial retirement plan, I think you’ll agree that your plan for spending and for mix of stocks and bonds will shout “Conservative” to you. I definitely think of our plan that way. But that plan could very well be labeled “Aggressive” – implying you are imprudent and overly risky for an intelligent, sensible retiree. You’ll most likely have to shut your ears to those who only look at one piece of the puzzle.