My nephew Rob read last week’s blog. He liked it, but I was not clear enough on the concept of Holding Period and how that affects his choice of mix of stocks and bonds – your choice, too, if you are building your nest egg. The purpose of this post is to explain: What’s a Holding Period and How do I Use Holding Periods to get to a proper mix of stocks and bonds?

== For those in the Save and Invest phase ==

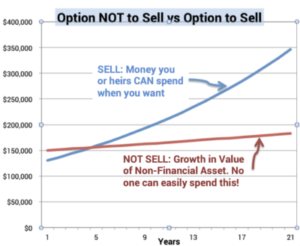

This blog is most useful for those, like Rob, in the Save and Invest phase of life – those building a nest egg. My point in this post is that it makes sense to think through when you will to sell an investment to get the cash you will spend. When you think it through, you have different time horizons. You decide your mix of stocks and bonds for those different time horizons. That’s how you get to your total mix of stocks and bonds.

Most folks just look at their portfolio as one big lump of money without regard to how long parts of it will sit untouched. They’re setting their mix of stocks and bonds for their one big lump. They fret about the ups and downs of the whole lump. This does not make sense to me. Why would I be concerned about what is happening in the stock market now for money that I will not need for spending for decades? Envision your portfolio as divided into groups of Holding Periods, each with a proper mix of stocks and bonds. That’s the way you get to your total mix of stocks and bonds. Also, when you think of your portfolio this way, you’re less alarmed when you see the total decline because you may have parts that have not fallen at all.

== It’s different for us retired folks ==

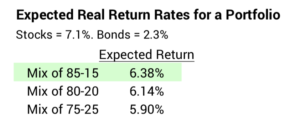

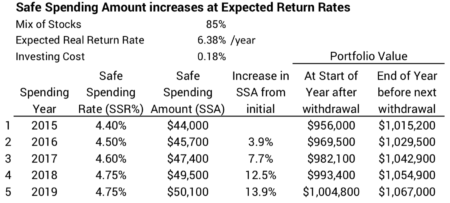

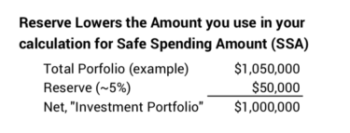

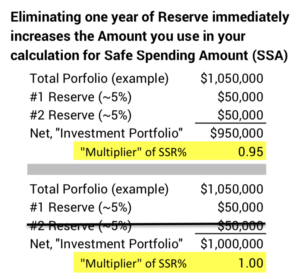

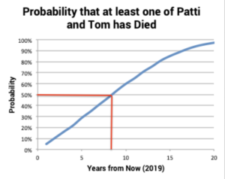

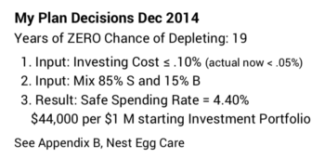

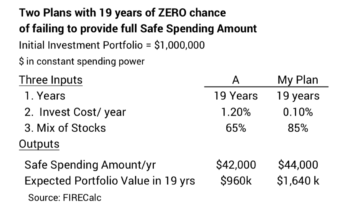

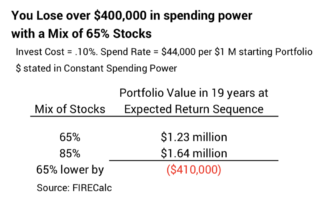

For those of us in the Spend and Invest phase of life, the practical matter is that a Retirement Withdrawal Calculator (RWC) tells us a lot more about what we should have as our mix of stocks and bonds. Rob’s building a nest egg. We retirees are trying to spend from it and not deplete it to an unacceptable level. Decisions for our retirement plan are more complex than for Rob: we have to get to a Safe Spending Rate (SSR%) and we only get that from an RWC (See Nest Egg Care). The thinking on Holding Periods is not precise enough to tell us what’s Safe to Spend, and that’s the biggest factor for safety of our retirement plan.

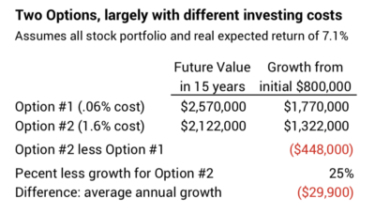

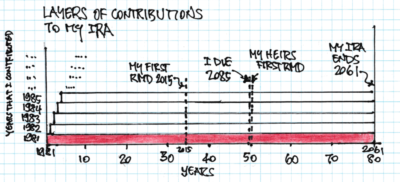

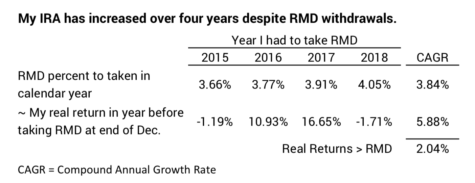

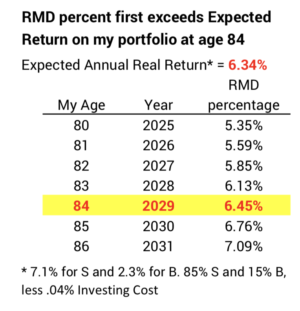

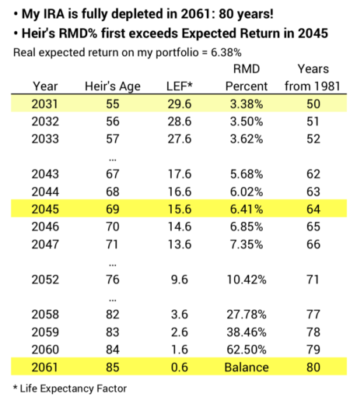

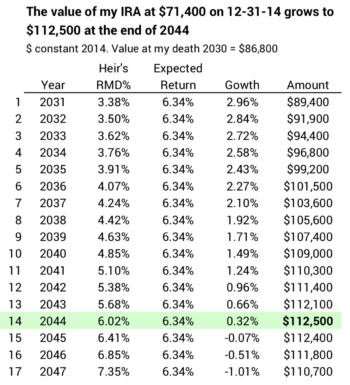

An RWC also tells us how mix (and Investing Cost) affects our portfolio over time. I picked mix for us at the start of our plan and will keep the one I picked for the rest of our lives. Each December, however, I like to recast or envision our portfolio by three Holding Periods. I see the parts are behaving exactly as one would expect.

== What’s a Holding Period ==

A Holding Period is the length of time that you hold onto an investment before you sell it for spending. The most obvious example is the contribution Rob will make – ideally – to his Retirement Account this year – his 401k at work and perhaps also to his Roth or Traditional IRA. Rob is 25. He will not sell securities from his Retirement Account for at least 35 years. Rob’s contribution this year – let’s assume $6,000 – will compound and grow for 35 years. That’s his holding period for this year’s investment. He actually could open an account just for this year’s contribution and nickname it. (This would fit in the nickname space on my Fidelity portfolio page.)

He could open a new account in his master Retirement Account every year and similarly nickname each. It would be clear: each year’s contribution would have at least a 35-year Holding Period. This can get cumbersome, but you get the idea.

Here’s a different one: Rob thinks about his future spending needs and thinks he will spend $20,000 for a new car three years from now. He could actually open an account at his brokerage house – it wouldn’t be part of his Retirement Accounts – and nickname it, “For my new car in summer 2022.” He has some saved now and puts that in this account. He’ll add to that to get to the $20,000. This means the amount he has now has a Holding Period of three years. The amount he adds next month will have a holding period of 35 months. Next is 34 months. And so on. Let’s group all those into one 0-to-3 year Holding Period.

== Long Holding Periods and Mix ==

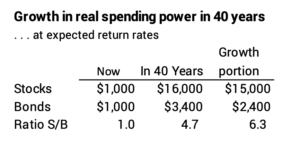

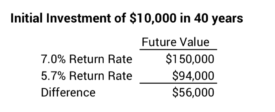

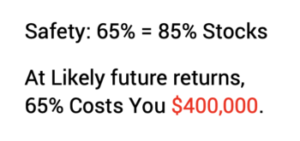

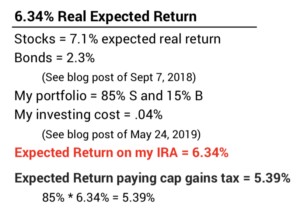

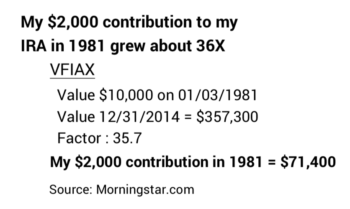

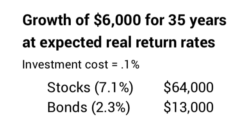

The mix of stocks and bonds for a 35-year Holding Period is really obvious. Over that long of period, nothing will beat stocks. Bonds won’t come close. At expected returns, stocks will pound bonds. Stocks at 7.1% will compound to roughly 11X in spending power. Bonds at 2.3% will compound to roughly 2X.

Both stocks and bonds are variable in returns. Both have had long periods of returns well below their expected return rates. For a 35-year Holding Period, though, bond returns never have surpassed stock returns. The conclusion is clear. Rob’s investment this year into his Retirement Acccount has to be 100% stocks and 0% bonds. His investment next year – with the plan for another 35-year holding period – has to be 100% stocks. The sum of the two is 100% stocks. This pattern repeats for MANY years.

Actually, Holding Periods less than 35 years should be 100% stocks. We whittle the 35 years down in two steps.

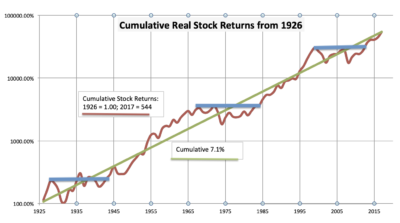

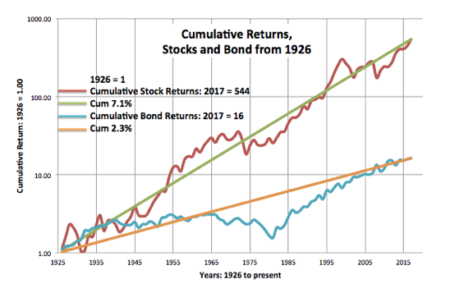

1. We can first cut the years Rob should be 100% stocks in half. At about 17 years – 17-year Holding Period – stocks are LESS variable in return rate than bonds.* You get a sense of this from this graph: historically bonds have departed much farther below their long-term average return line than stocks.

To restate, for a Holding Period of ≥17 years stocks are 3X better in expected annual return and are less variable in annual return rate than bonds. That’s a clear mark: Holding Period ≥17 years HAS to be 100% stocks.

2. Now we get to a judgment on your choice – your bet – for mix of stocks vs. bonds based on less obvious probabilities. I conclude that Holding Periods of 10-years or more should be 100% stocks. The future chances that bonds will outperform stocks for a 10-year holding period is very small. And the amount that bonds may outperform is small. All the other times – when bonds don’t outperform – stocks will compound to much greater value than bonds.

Stocks don’t always outperform bonds over ten-year Holding Periods. Historically bonds have outperformed stocks over ten years about 20% of the time. But most all these occasions occurred in periods from the 1980s when inflation fell from its high of 13% to about 2%. Bond prices move opposite to the direction of interest rates. Prices of bonds rose dramatically with that dramatic fall in interest rates. You see that effect in the graph above: the steep increase in bond returns starting in about 1980. Today interest rates can’t fall like that and prices can’t rise like that in the future. The chance that bonds outperform stocks over a 10-year Holding Period in the future is a lot less than 20%. (Also see NEC, End Notes Part 2.)

== Short Holding Periods and Mix ==

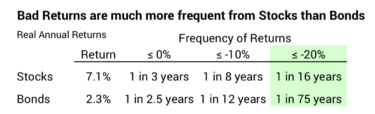

The mix for a 0 to 3 year Holding Period is a bit more complex. Stocks are much more variable than bonds for one-year return periods. for example, a bad 1-in-10- year event for stocks is -16% or worse real return. When stocks have a negative return like that, bond returns have been much better. Rob wants that money for the car to be there in three years, so he would tend to conclude, “Easy: I want 100% cash and bonds for that.”

That’s a good choice, but not exactly the best choice. A good thing happens when you mix a little bit of stocks in with the cash and bonds: you get less variation in return and you get greater expected return. You get less variation because the peaks and troughs of the real returns for the two don’t align. Enough of the upswings of stocks cancel enough of the downswings of bonds and vice versa to result in a smoother, more predictable total ride. And it’s a better ride because that bit of stocks increases the expected return to more than you would get from bonds only. More predictable return and better return. You have to like that. The math guys work the details on how peaks and troughs offset and tell us a really good mix for this Holding Period works out to be 80% bonds and 20% stocks. I buy that.

== In between ==

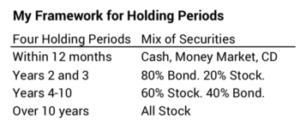

If a Holding Period of 0 to 3 years is 80% bond and 20% stock and a holding period of ten years and longer is 100% stock, what comes in between?

You basically want a transition that goes from 80% bond to 0% bond from years four to ten. Sketch that out on a graph, and it averages out to 60% stock and 40% bond over that period. The math guys also say that 60% stock and 40% bond mix is good for this band of Holding Period.

== My matrix and look =

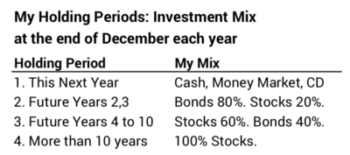

Each December 15 I recast my portfolio into these three Holding Periods with those mixes. (I keep spending for the upcoming year in cash.)

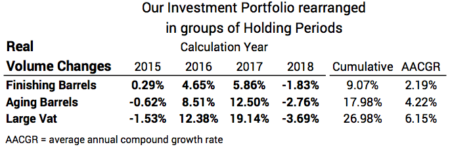

I know my stock and bond returns by the way I’ve organized our accounts. For a mix of 80% bond and 20% stocks I should see lower returns over time but less variation in return. For my Holding Periods that are 100% stocks I should see greater returns over time but much more variation. And the in between should be, well, in between. That’s what has happened over the four years I’ve been doing this.

Conclusion: When your are building your nest egg, think about Holding Periods: how long you will hold onto an investment before you sell it for spending. Estimate your spending needs into Holding Periods. Each period should have a proper mix of stocks and bonds. I like this as Holding Periods: A) upcoming year (basically all cash), B) following years 2 and 3, C) years 4-10, and D) over 10. When you do this, you will get to a proper total mix of stocks and bonds.

* See Chapter 6, Stocks for the Long Run. Jeremy Siegel. This is an excellent discussion of “Risk, Returns, and Portfolio Allocation”.