Blog reader Bill is starting out on his plan. He’s figured out what he can pay himself from his financial nest egg and asks, “We now have a long string of years without a major market decline. Are we ripe for one? Should I start out spending less than my calculated SSA?” Good question! I wrestled with that question four – almost five – years ago when I started my plan. And that thought crosses my mind in early December when I Recalculate for next year’s Safe Spending Amount (SSA). (See Nest Egg Care (NEC), Chapter 9.) This post expands on my basic answer: I don’t think we are close to conditions that would lead to a huge market decline that sinks your portfolio. But if it makes you feel better and safer, increase your Reserve (See Chapter 7, NEC); that has the same effect as lowering your SSA – your paychecks from your nest egg.

Here are some basic reminders.

== Your plan always assumes the worst ==

The key planning assumption for NEC is that we retirees will face the MOST HORRIBLE of financial returns in history essentially starting TOMORROW. This most horrible sequence of returns will have a devastating effect on our portfolio, but we can take actions that assure zero chance of depleting our portfolio for many, many years.

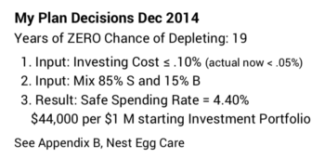

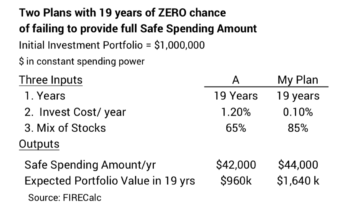

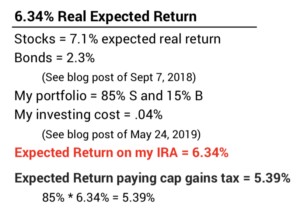

The key action we take is to have a low Safe Spending Rate (SSR%) and that results in a low Safe Spending Amount (SSA). (Maybe we could debate: is being a low cost investor more important than this action or just a prerequisite?) I found the SSR% for Patti and me at the start of our plan – for 19 years with zero chance for depletion of our portfolio – was 4.40%. (See Chapter 2, NEC.) That equates to LESS THAN 0% real annual return over 19 years. If we had assumed 0%, our spending rate would be 1/19 or 5.25%.

The fact that our SSR% is based on less than zero cumulative return reflects the ugly annual declines in returns within the long sequences of 0% cumulative return for stocks (18 years) and for bonds (48 years!).

== The worst is REALLY BAD. And rare. ==

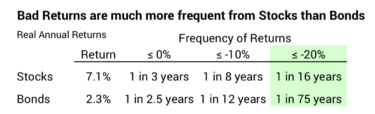

The worst sequences of returns that sinks your portfolio – basically for any mix of stocks and bonds – includes a few years of SHARP, NEGATIVE stock returns that eat up roughly 45% of the spending power of your stock portfolio. This damaging decline from stocks has to hit you in within the first five or six years of your retirement to have its most devastating effect. That’s when a large percentage decline eats the most dollars relative to your starting portfolio value. When you combine the effect of withdrawing for spending, it gets really hard to replace those dollar losses even when returns improve. Bonds have not been golden: they’ve cratered and eaten 41% of spending power over a five-year period.

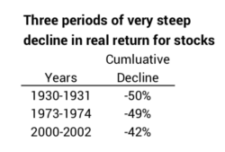

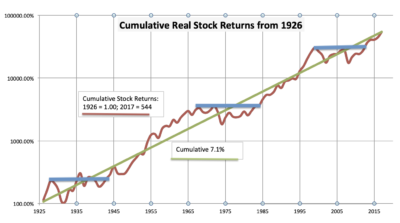

We’ve had VERY UGLY real declines for stocks three times in the 92 years since 1926 – that equates to a 1-in-30 year event. (It’s a 1-in-50 year event had I considered the return data from 1871.) Those steep declines don’t have to hit us right at that start of our retirement to really hurt us, meaning the chance that we’ll suffer a major decline in our portfolio within a few years from the start of our formal retirement plan is greater than 1-in-30. It’s still fairly rare. You can see more scary periods of historical returns for stocks here and read about the worst sequence that drives our spending rate to a low level here. That sequence has the two-year -49% real decline from stocks and the five-year -41% real decline from bonds! Wow.

== Your Reserve buys a layer of Safety ==

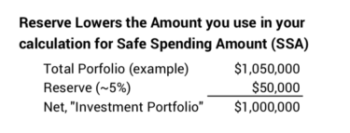

Nest Egg Care adds a layer of safety to your plan by asking you to take 5% off the top of your total portfolio – roughly one year of spending. (See Chapter 7, NEC.) In effect, you stick that Reserve under a mattress and try not to think it even exists. You base your calculation for your Safe Spending Amount (SSA) on the net, which I call your Investment Portfolio. The 5% Reserve lowers the dollar value you’re using to get to your SSA and that lowers your SSA by 5%.

Hopefully you will never have the need to tap your Reserve, but you will use it for your spending when we hit an annual return or several years of return that are really scary. We are not selling securities – especially stocks – from our Investment Portfolio. We’re giving ourselves a shot for stocks to rebound, side-stepping severe damage to our portfolio.

==== Do I think MOST HORRIBLE is near? ====

No, I don’t.

• Statistically a bad 1-in-10 year event is a real decline of -17% or greater. We’ve not had a year like that for more than ten years. But that does not mean the chance of a really bad year is increasing. Our last year like that was 2008, and it was much worse than -17%; 2002 was another year; we have to stretch back 27 years to 1974 to find the next prior year.

• I think it’s the economy that will drive the next steep decline: recession, depression, or out of control inflation. We combined several recessions and very high inflation averaging over 7% per year for the 15 years starting in 1969 – that’s the start of the Most Horrible sequence of return that we use to set our SSR%. I don’t see any conditions that suggest we are close to those conditions. Do you?

• The other concern is an over-heated market or over-priced stocks. All three of the years that kicked off declines (1930, 1969, 2000) came after a period of very high stock returns. You can see those run-ups as deviations well above the long-term trend line in the graph below. They even look like bubbles. When I look at the pattern of stock returns now, I don’t see a deviation – a bubble above the long-term trend line.

== We make decisions based on emotion ==

We make decisions by emotion and not by logic. We’re human! I can completely understand that if Nest Egg Care tells me a spending rate is safe then by gosh I’m going to do something to make it even safer. It’s just too important. I can do two things that are logical for greater safety:

#1) Lower my spending rate. Bill’s absolutely right. That’s the number one lever to increase safety by far. Lower spending BY JUST A LITTLE means a longer shaft length of your hockey stick – the years with zero chance of depleting your portfolio. (See Chapter 2, NEC.)

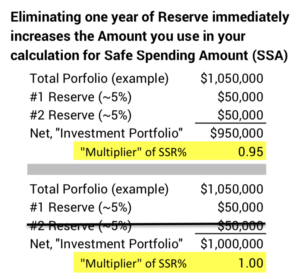

That’s essentially what Patti and I did at the start of our plan. (See NEC, The Patti and Tom File at the end of Part 2.) Patti wanted two – no three – years of spending in Reserve. We negotiated: I put two years into Reserve. That lowered our SSA by another 5%. That is what I would recommend to you: increase your Reserve. That means you are lowering your SSA. I like this approach better than just spending less than your calculated SSA. You don’t want to get into the habit of “Saving” part of your calculated SSA. That simply means you aren’t enjoying (and giving) as much as you should.

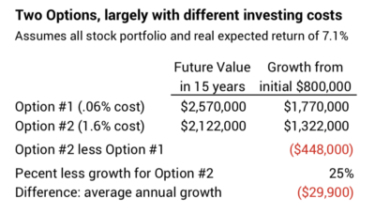

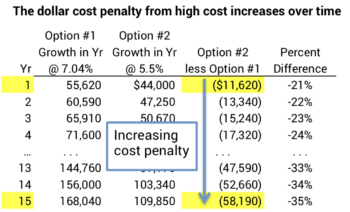

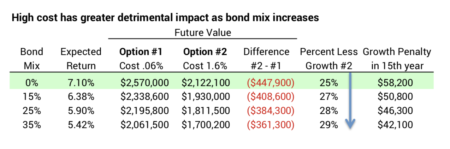

#2) Lower my Investing Cost to less than that assumed in Nest Egg Care (NEC) – .18%. Lower cost is always a good move, but lowering to less than .18% is a small lever: it does not come close to #1 in lengthening the shaft of your hockey stick. Our Investing Cost is less than one-fourth that assumed in NEC. That took no work: fund companies have continually lowered their Expense Ratio for the funds Patti and I own.

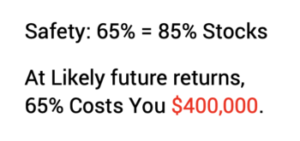

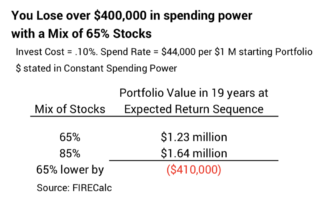

Those two ARE the options. It is not logical in my mind to have a low mix of stocks. Or to throw other kinds of investments than stocks and bonds into your mix; those actions aren’t buying you added safety that you otherwise would get from #1 and #2. Anything less than 75% stocks makes NO SENSE to me. Nothing about less than 75% stocks is “more conservative” in my mind. See Chapter 8, NEC.

== Drop that extra Reserve? ==

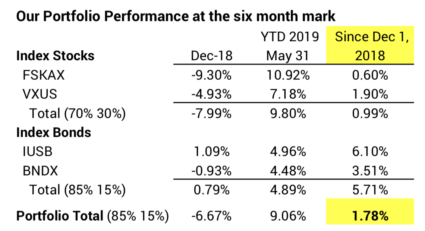

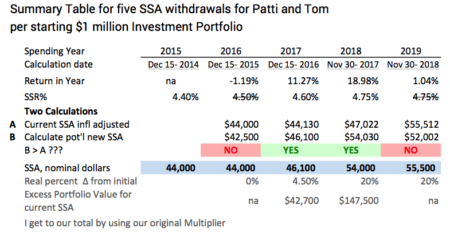

Over time Bill will Recalculate (Part 3, NEC), hopefully, to a greater real SSA. Then he can rethink the need for that extra Reserve. Patti and I started at SSA of $44,000 per $1 million of Investment Portfolio. Now our SSA is 20% greater in real spending power. I have not lowered that original two-year Reserve, though. Doing that would immediately boost our SSA by 5% because it would immediately increase our Investment Portfolio. But I have no big urge to do that. No urge to explain why I want to lower the Reserve to Patti. Maybe I’ll do that the next time I Recalculate to the next real increase in SSA. Maybe not.

Conclusion. We all worry that we aren’t being conservative enough for our financial retirement plan. I assert that the Safe Spending Amount (SSA) that you get from Nest Egg Care is darn conservative. But it’s human nature to be more conservative than what someone else recommends. If you want to be more conservative, increase your off-the-top Reserve – the amount that is not part of the math to get to your SSA. In effect you are lowering your SSA. That has the effect of adding years of zero chance of depleting your portfolio.