I read this article this week, “6 Portfolio To-Do’s for Retirees at Midyear”. I don’t do ANY of the six. This post describes what I don’t do mid-year and why.

Here are the steps in the article:

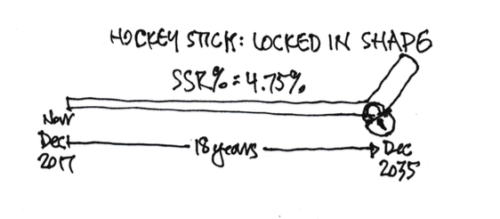

1. Check your year-to-date spending rate. I don’t need to check this. I already know where Patti and I stand, almost on a daily basis. I calculated our Safe Spending Amount (SSA) last December. Our spending rate now is 4.75% up from 4.40% at the start of our plan (January 1, 2015). Our 2018 SSA is $54,000 relative to $1 million Investment Portfolio at our start. (The terrific returns in 2017 gave most of the boost from our initial $44,000.)

Since we pay ourselves 1/12th the annual total (direct deposit from our Fidelity account into checking), all I really need to look at is our checking account: Have I had to advance a paycheck because we’ve run out of money in a month? (No.) Do I get close to zero at the end of every month? (No.) Am I building cash this time of year that tells us we should work harder to spend to ENJOY or start thinking about gifts at the end of the year? (Yes)

The article says a retiree starting their plan should use 4% as his or her spending rate. Nest Egg Care (NEC), Chapter 2 is far more precise. The percentage changes with age: for once it’s better when you are older. That 4% rate applied to our Investment Portfolio would have been 10% too low for Patti and me at the start of our plan and would be about 20% too low now.

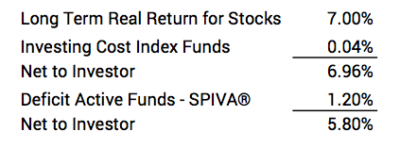

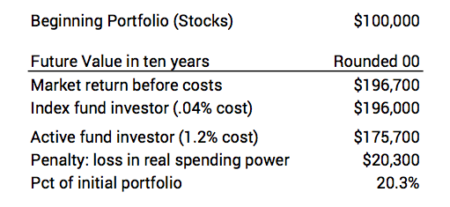

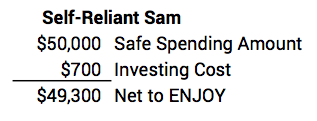

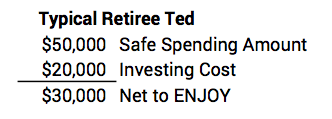

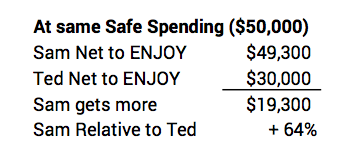

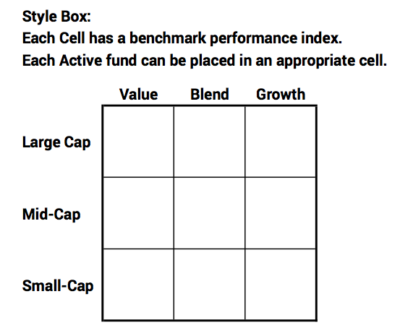

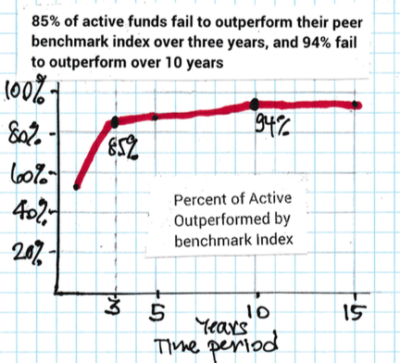

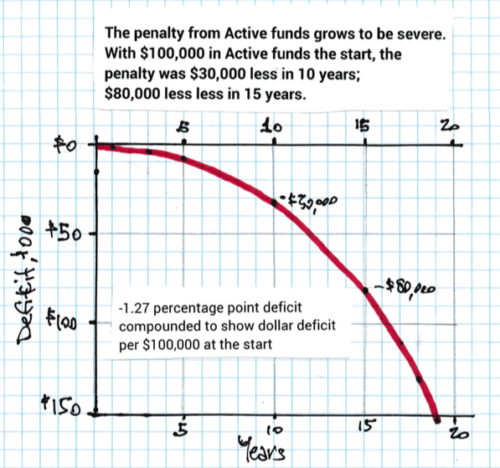

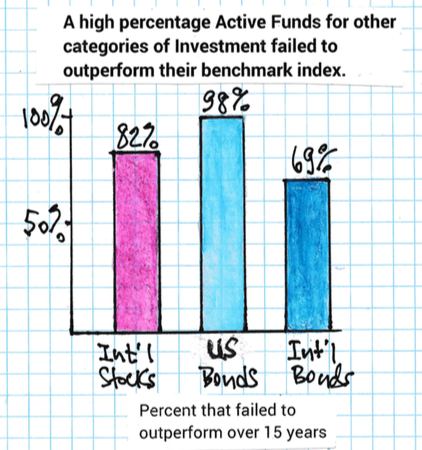

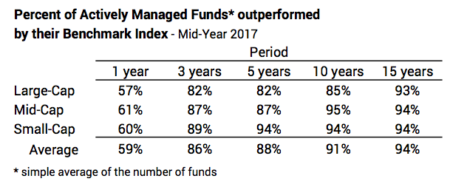

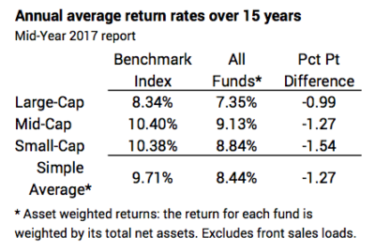

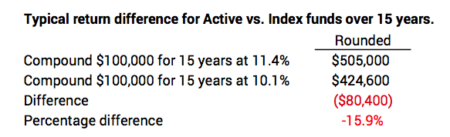

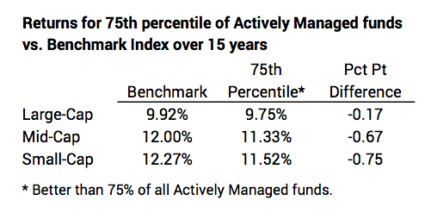

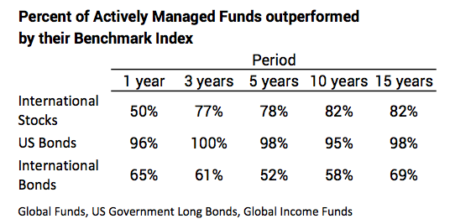

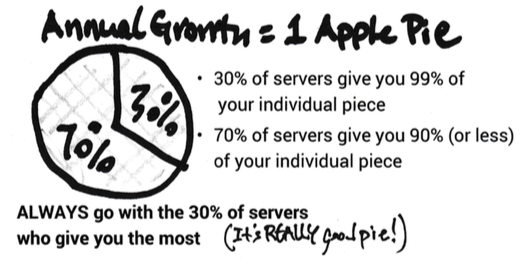

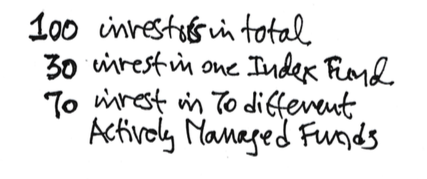

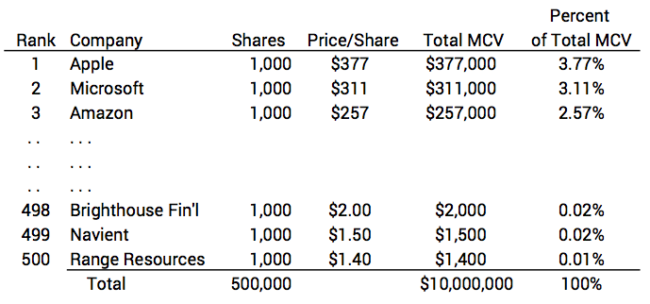

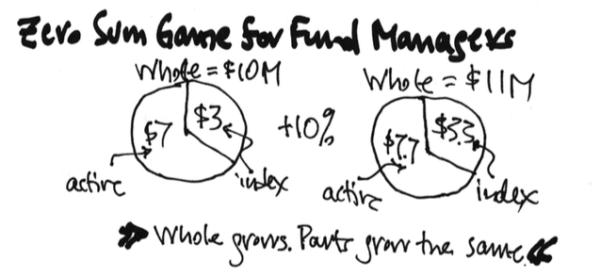

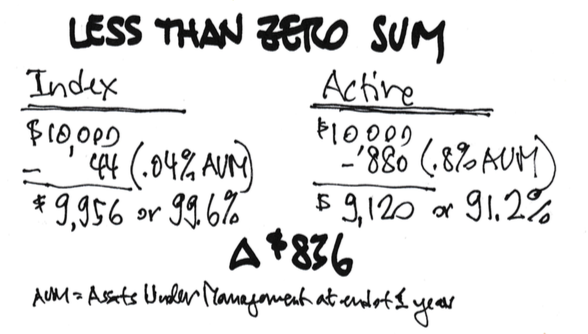

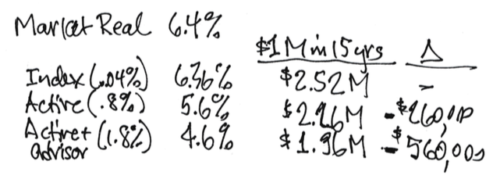

2. Check the asset allocation of your portfolio. The article says allocation of stocks and bonds is the second most important decision after spending rate. It’s really a distant third. Clearly your decision on Investing Cost is a very close second to Spending Rate to maintain long-term health of your portfolio. (I could argue that it’s the essential starting point of any retirement plan. You find out that in NEC, Part 2.) I set our stock and bond mix at the start of our plan, and that allocation does not change.

The article also says that a retiree should have two years of spending in cash. NEC recommends a 5% Reserve or basically one year of spending, but Patti and I chose two years in Reserves (Part 2), and I invest that in a Short Term Bond fund. (And I’m now including the value of 529 Plans that we “own” as part of our Reserve.)

3. Take a closer look at your cash. Again, I don’t need to do this. The only cash we have (Money Market or Checking) is the unspent balance of our 2018 SSA.

The article says one might want to increase cash because money market rates are increasing. This makes no sense to me. Rates are increasing because inflation is increasing. I’d guess the real return on Money Market is below 0%.

The article suggests “opportunistic” retirees might want to boost cash so they could bargain hunt if stocks or bonds fall. That makes no sense to me. We retirees should not be betting that we can boost returns by timing market moves. I don’t think anyone can do that successfully over what we all hope is a decades long retirement period.

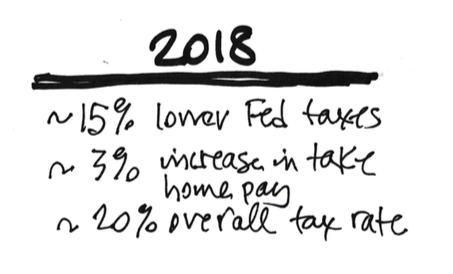

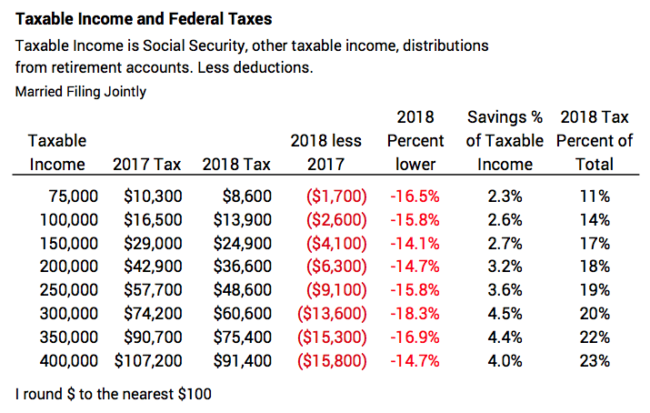

4. Take a fresh look at IRA conversions. The conversion is Traditional IRA to Roth IRA. For most all of us we’d be considering how much we might save in taxes by incurring a 22% tax rate now (Traditional) for the conversion to, maybe, avoid 24% tax rate later (Roth). The tax brackets are pretty wide. I suspect the marginal rate for most of us is 22%, starting at $77,400 for married filers; that marginal rate runs to $165,000 before the 24% rate kicks in. You’ve got to be at the edge of one bracket to even give this a thought. Predicting your future taxable income is really tough. (The change in value of your retirement accounts and Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) will be the biggest consideration.) Predicting how much of your RMD income might tip you into a higher marginal bracket is tough. The two-percentage-point difference is small. Converting would make zero sense for all but a rare few of us.

5. Develop an action plan for your RMD. I don’t need to figure that out now, since my process steps and calendar were set when Patti and I started our plan. (See Chapter 13 Nest Egg Care.) Our process is to take RMD the first week of December. We calculate our Safe Spending Amount (SSA) for the upcoming year. SSA certainly is greater than RMD, not just for Patti and me but for all retirees. So all retirees are going to take their RMD, but need to sell more securites to get to thier SSA. Largely because the lower tax bite on capital gains, most all will sell securities in their Taxable Account to get to their total SSA for the upcoming year.

The article gives some advice to those who don’t spend their RMD. Why wouldn’t you spend (or gift) all your RMD and more? Why so little? Pay yourself your full SSA!!! Spend and gift it ALL in the year.

6. Revisit your Charitable Giving Strategy. We don’t rethink our strategy. That’s set. In October we have to figure out if we will spend our full 2018 SSA by the end of the year. If not, we will gift to those we love and donate the balance to charities we really like.

We really like gifts to 529 College Savings Plans. For donations, our process is to first donate as Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) from my IRA account. (I’m over 70½ and can do that; Patti hit 70½ this year.) It never hurts (and could help) by donating directly from your Retirement accounts (see Chapters 10 and 13). Our retirement accounts are at Fidelity, and it’s pretty painless to execute the QCDs.

If I donate from our taxable account, I always donate my most highly appreciated securities to our account at the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund (FCGF) – a donor advised fund. (Others, like Vanguard or Schwab, have similar funds.) And then I ask it to make the donations to those on the list I’ve given them. This is a big time saver for me. Fidelity makes it very easy to find the securities in our taxable account with the lowest cost basis and move them over to FCGF (Donating securities with lowest cost basis give best tax advantage.)

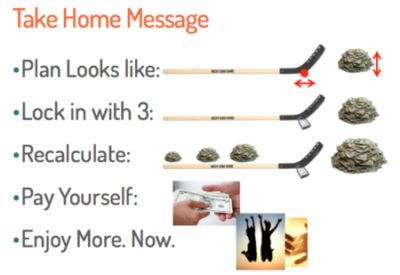

Conclusion. If you set up your plan and process as suggested in Nest Egg Care, you really have very little to do during the year. You certainly do not have 6 Midyear To-Do’s. Your real work is concentrated over a few days after your calculation date. The work for Patti and me starts right after November 30.