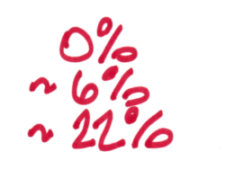

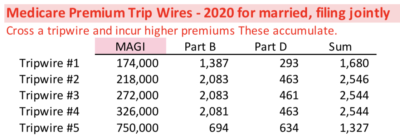

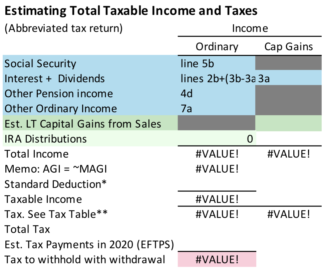

The purpose of this post is to explain how your Social Security (SS) benefit is taxed. The percentage taxed ranges from 0% to 85%. How is the exact percentage calculated? When I google the question, I find the descriptions are VERY CONFUSING. It’s important to understand how your SS benefit is taxed year if you are subject to RMD. You can forego your RMD this year because of the CARES Act. Forgoing RMD obviously lowers taxable income this year, but it may also lower the percentage of your Social Security benefit that is taxable. Lower taxes on top of lower – really delayed –taxes.

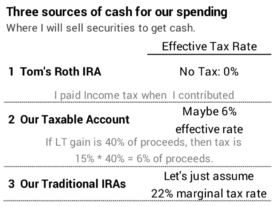

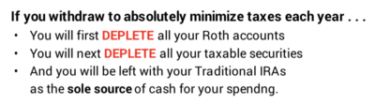

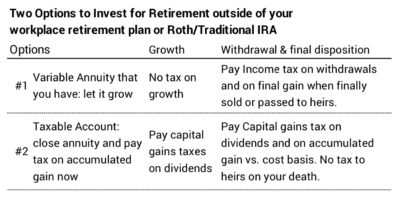

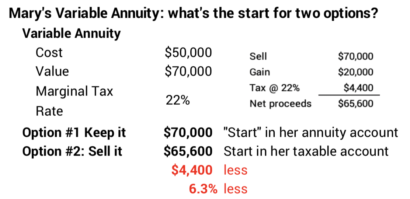

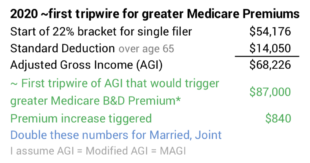

And some can drive taxes even lower. They might be able to “manage” income – perhaps postpone sales of securities that delay capital gains taxes – to drive total Taxable Income (Adjusted Gross Income less the Standard Deduction) below ~ $40,000: that would lower capital gains tax to 0%. I wrote on this topic last year, but this post focuses on a clearer description of how SS benefits are taxed.

== Gory details but simple in concept ==

The details of how your Social Security (SS) benefit is taxed are in IRS publication 915, but it was Very Hard for me to fight through that and its worksheet to understand what’s going on. Here’s the basic concept:

The percentage of your Social Security benefit(s) that is taxed is determined by the amount of income you have in addition to your SS benefit. Low or relatively low amount of Other Income = none of your SS benefit is taxed. Moderate to more than moderate Other Income relative to your SS benefit = up to 85% is taxable income. High amount of Other income = 85% of your benefit is taxable income.

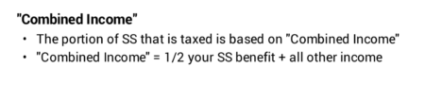

== “Combined Income” ==

The amount of your SS benefit that is taxable depends on your “Combined Income”. This is a special term just for this calculation. Combined Income = ½ of your SS benefit + all Other Income. All Other Income for this definition is wages, interest income (taxable and tax exempt), IRA distributions, other retirement income, dividends and capital gains. See the IRS publication and worksheet for special tweaks.

== 1. Base Threshold.

2. $9,000 or $12,000 more.

3. The balance. ==

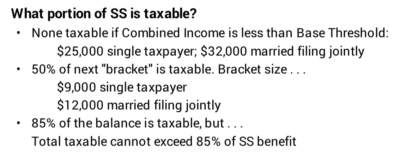

You can think of this as three tax brackets with a cap on the total percentage of your SS benefit that is taxable.

1. If your Combined Income is below a Base Threshold amount, none of your SS benefit is taxable. The Base Threshold amount is $25,000 for a single taxpayer and $32,000 for married, filing jointly.

2. 50% of the next amount of Combined Income, up to $9,000 more for single taxpayer and up to $12,000 more for married filing jointly, is taxable income. For example, for a single taxpayer, that’s up to a total of $4,500 taxable income for this bracket.

3. 85% of Combined Income greater than the top of the prior bracket is taxable. But the total taxable amount cannot exceed 85% of the full Social Security benefit.

== My generalizations ==

Here are my rough generalizations after playing with the spreadsheet here that you can download and use to figure out how much of your SS benefit will be taxed:

• Folks who have Other Income that is not more than ~60% of their full SS benefit have no taxable SS benefit;

• Folks who have Other Income that is ~160% of their full SS benefit will max out at 85% of the benefit as taxable income.

• Folks in between will see an increasing percentage that is taxable rising from 0% to 85%.

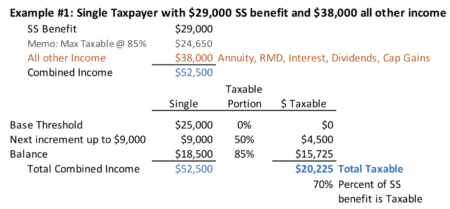

== Example #1 ==

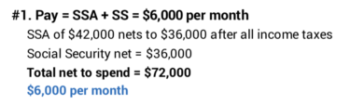

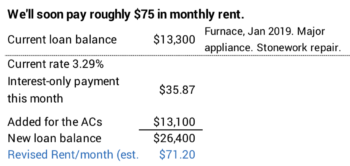

In this example, Joyce, single taxpayer, has SS benefit of $29,000 and all other income of $38,000. (Other Income is about 130% of her SS benefit; she should fit in the “in between” category.) I assume in this example that $25,000 of the $38,000 is distribution from her IRA. The result is that 70% of Joyce’s SS benefit is taxable income: $20,225.

== What about 2020 and no RMD? ==

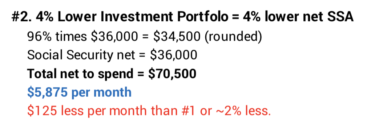

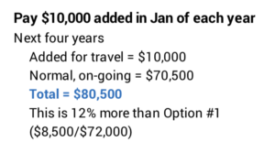

In 2020, Joyce is not required take RMD because of the CARES Act. But she wants $25,000 of gross proceeds from sales of securities for her spending in the upcoming year.

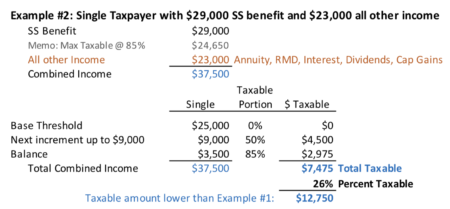

She decides not to take RMD but to sell taxable securities for $25,000 gross proceeds. Let’s assume 40% gain or $10,000 of capital gain income. That’s $15,000 less Other Income for the calculation of how much SS benefit is taxable income.

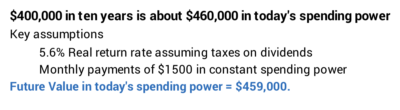

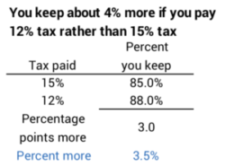

Example #2 shows the effect. The taxable amount of SS benefit drops to ~$7,500. ~$13,000 less than Example #1. At 12% marginal tax bracket, this is likely ~$1,500 lower tax.

And some may be able to get an added tax benefit. The lower total Taxable Income – lower in total by the $28,000 in the example above: $15,000 from substituting capital gains for RMD income; $13,000 from lower SS taxable income – would mean that none of Joyce’s $10,000 capital gain is taxed. Her total Taxable Income (Adjusted Gross Income less her Standard Deduction) would have to be less than ~$40,000 to get to 0% tax on capital gains. I described how this might work in last year’s post.

Conclusion: The taxable portion of Social Security benefits range from 0% to 85%. I I found it difficult to understand how that percentage is calculated. I tried to make the explanation clear in this post. I also provide a spreadsheet you can use understand how much of your benefit its taxable. It’s more important for older retirees who may chose not to take RMD to understand how Social Security is taxed this year. They could lower the percentage of taxable Social Security benefits and total income taxes by a meaningful amount.