Should you invest in a Variable Annuity to help build your nest egg?

Posted on July 24, 2020

Variable Annuities are popular. Investors poured over $240 billion into them in 2019. I opened a variable annuity account at Fidelity maybe 15 or 20 years ago as added way to save for retirement. I’m not remembering my thought process, but I’d guess that I had contributed the max to our IRAs and had more I wanted to save for retirement. I was attracted to deferral of taxes on the growth that you get from a variable annuity; I’d only pay tax when I withdrew for spending. That tax deferral sounds appealing, but is it? The purpose of this post is to explain why I think you should NOT invest in a variable annuity to build your nest egg for retirement.

== Never as good as a Traditional or Roth IRA ==

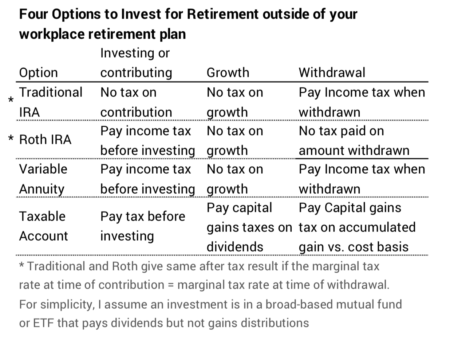

Where do you invest for retirement? You have four basic options outside of your workplace retirement plan. You’re down to two options once you’ve maxed out on the amount you can contribute to your Traditional or Roth IRA: 1) open a variable annuity account and invest in one of the mutual funds it offers; 2) keep the amount your taxable account, invest in a broad-based mutual fund or ETF (See Chapter 11, Nest Egg Care) and pay capital gains taxes on the annual dividends and accumulated gains.

A variable annuity is somewhat similar to a Roth IRA, but clearly not as good. (I’ll use Roth as a comparison but Roth and Traditional IRAs give you the same after-tax dollars assuming the tax bracket at the time of investment or contribution is the same at the time of withdrawal.) You’re investing after-tax dollars, just like Roth. Like Roth, you don’t pay any taxes on the growth. But unlike Roth, you pay income tax on the growth when you sell and withdraw for your spending. This means a variable annuity will never match the results of your IRA – you won’t have the same after-tax results.

== Better than investing in a taxable account? ==

But the question is – once you’ve met your limits to invest in your IRA – is a variable annuity better than investing in essentially the same mutual fund your taxable account? The basic answer is “No.” Here are the two basic options and tax considerations:

Case #1: You have high enough income now that you pay 15% tax on dividends (and gains distributions) from your mutual funds. That means, basically, that you are in the 22% tax bracket; that’s the approximate threshold where gains taxes change from 0% to 15%.

When retired, you believe you will have enough ordinary retirement income – e.g., Social Security, income from defined benefit retirement plans, and your withdrawals from your Traditional IRA – that you will be in the 22% tax bracket. (In 2020, the 22% marginal tax bracket starts at Adjusted Gross Income of $107,650. Half this for single files over age 65.)

Conclusion: it makes NO SENSE to invest in the variable annuity. You do NOT want to defer paying 15% taxes to eventually pay 22% tax. The added benefit in growth from deferring payment of capital gains taxes can’t make up that difference.

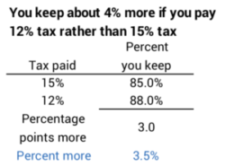

Case #2: You have high enough income now to pay 15% tax on capital gains, but you are convinced that in retirement your ordinary income will NOT cross into the 22% tax bracket. You’re convinced that you’ll be in the 12% bracket for many years. (You will be well below the threshold stated above.)

If you invest in a variable annuity, you’re otherwise avoiding 15% tax on gains and eventually you’ll pay 12% on the growth. This starts to make sense: you get to keep about 4% more of the growth in this case. A variable annuity may be attractive.

== We’re not done yet: higher costs ==

You pay added fees for the privilege of deferring taxes on growth in a variable annuity. These costs are a direct reduction in the return you get. What are the added costs?

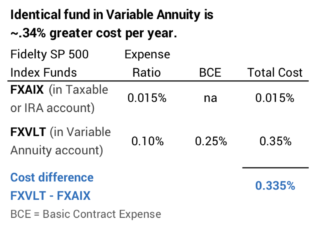

You pay a Base Contract Expense on the value of your variable annuity in addition to the Expense Ratio of the fund that you invest in. (This article describes this expense as Insurance Charges.) Think of this as a fee that simply allows you to defer taxes on growth, because that it all it really does. The fee goes to an insurance company or perhaps an insurance subsidiary of the firm offering the variable annuity: Fidelity, Vanguard, or Schwab would be examples. Why is an insurance company involved and why is this a true added cost? I don’t know. That’s just the way the authorizing legislation set it up.

The Base Contract Expense varies widely. Morningstar reports that this fee averages 1.10% of portfolio value but ranges from 0.10% to 2.10%. This fee at Fidelity is .25%; it’s .27% at Vanguard; 0.60% at Schwab.

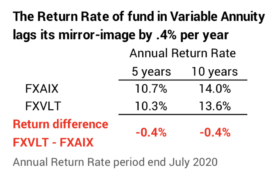

In some cases, you pay a greater Expense Ratio for the fund you own in your variable annuity account. Here’s an example: the same fund – or mirror-image fund at Fidelity – in the variable annuity has a total annual expense about .35% greater per year than the same fund in your IRA or taxable account. You’d expect the fund in your variable annuity to return .35% less year after year. This is the case in this example.

This added .35% expense lowers your expected your growth rate by about 5%. I divide the .35% added cost by the expected real return rate for stocks of 7.1%). This hit on growth is exactly why I closed out my variable annuity: it was easy for me to see that the accumulated growth in my variable annuity was far less than for the exact same fund in my IRA: I’d pay the same income tax rate when I withdrew from either one, but the fund in my variable annuity was growing far slower: I’d net far less.

== Back to Case #2: it doesn’t win ==

You’ve gone backwards on Case 2 now that we added in the effect of higher costs for the variable annuity. You got a tax advantage that meant you got to keep 4% more, but you gave up 5% of growth per year. You’re behind the game. You can see on this pdf that the relative small difference in costs wipes out the advantage of lower tax rate (12% on withdrawals and a final sale) as compared to 15% taxes on dividends and at the final sale. There’s no advantage to a variable annuity. It’s simpler and you’d be better off to keep the amount in our taxable account than with the variable annuity.

Conclusion: Once you’ve maxed out on your contributions to retirement accounts, you may still want to invest for retirement. You have two options: 1) just keep the amount in your taxable account, invest in a mutual fund, and pay tax on the dividends through the years; 2) open a variable annuity account, invest in similar fund, but defer all taxes until you withdraw: you’ll pay income taxes then. As I work through the options and cost differences between the two, I find no logical reason as to why you’d want to invest in a variable annuity. It’s better – and simpler – to just keep the amount in your taxable account.