A couple of weeks ago I mentioned this book, Dollars and Sense. I liked its thinking in Chapter 6. That chapter says that we are happier if we disconnect what we are buying from the action of actually paying for it. “We feel better [are happier] consuming anything that we have already paid for.” The authors’ example is of two couples that go on a vacation at a resort.

• One pays the all-inclusive price before the vacation. They ignore the posted prices for food, drink, and activities. Every day the simple thought is, “What’s the next fun thing to do today.” Whatever it is they want to do, they just do it.

• The other couple decides on pay-as-you-go. Multiple times each day they have to think about whether or not a specific item or activity is worth its price; they have to sign for each item or activity. At the end of the vacation they review the long list of charges, argue to correct a few, and then they have to pay. These folks have injected much more pain into the process of deciding what to spend and the process of spending. They are far less happy about their vacation.

We nest eggers are fundamentally happier than most retirees because we can view, in essence, our whole retirement as one big, prepaid vacation.

• We clearly understand the total we have at the start of our plan; we know we’ve invested it in a way that ensures we’ll be in the top six percent of all investors over time.

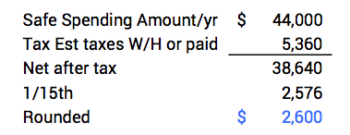

• We’ve decided what’s safe to spend each year. (See Parts 1 and 2, Nest Egg Care). That spending rate is set so we know we will never run out of money. We know our annual amount will never decline and will most likely increase. (Patti and I have increased by 20% over the last four years.)

• We put our Safe Spending Amount into cash and pay ourselves throughout the year so that we are free from worrying about small expenditures. We have “What’s the next fund thing to do?” foremost in our mind.

The purpose of this post is to explain my thinking of retirement as a prepaid vacation.

== We’re on an extensive cruise ==

We can view our whole retirement as an extensive, all-inclusive cruise. I’m going to say that we’re on The Nest Egg Care Cruise Line (The NEC Line). We step off land and join the cruise at the start of our retirement. This cruise truly is a once in a lifetime experience.

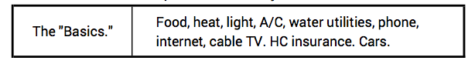

The NEC Line has a guide or manual (the Nest Egg Care workbook) that helps us divide the total pot of money we have at the start of the cruise into an appropriate annual amount (our annual Safe Spending Amount; see Chapter 2, Nest Egg Care). We’re more easily able to decide where we will stay on the ship: top-deck cabin for some, middle-deck cabin for others, and so forth.

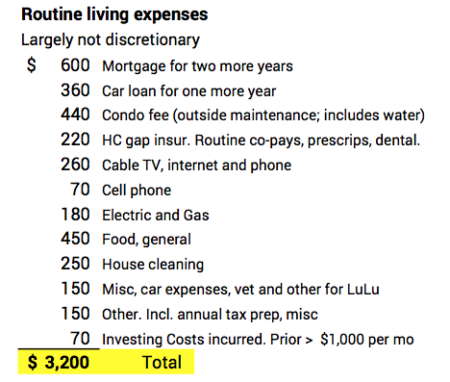

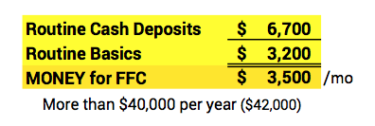

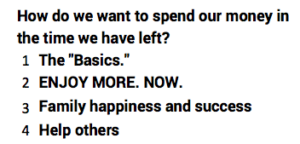

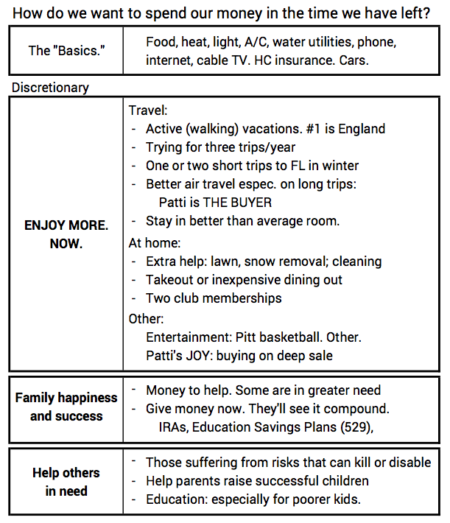

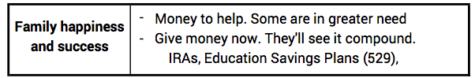

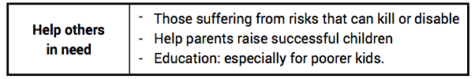

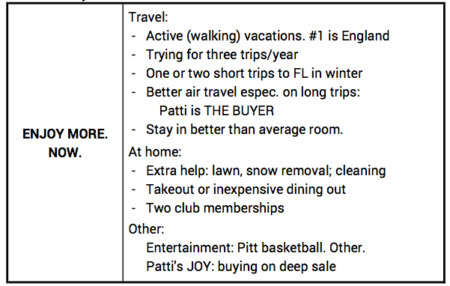

Our annual amount includes a complete package for those Basics and for an associated package for Fun, Family, and Community (FFC). The list of Fun activities is so long and far-ranging that we have to spend time picking what it is that we would enjoy the most.

== Cruise Currency and our Debit Card ==

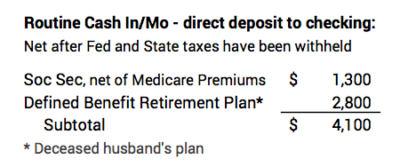

We have travelers from different countries on our ship. The ship doesn’t want to process spending in different currencies. It converts our dollars to units of Cruise Currency, for example. Social Security or other income is also converted to Cruise Currency. That’s what we spend on this ship, and it’s also good for all our spending in ports of call.

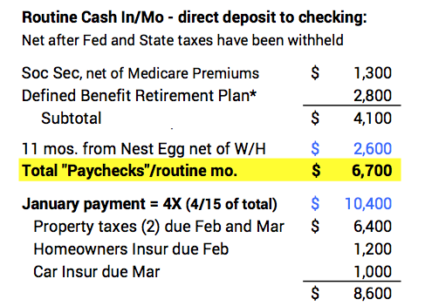

The NEC line subtracts our spending for the Basics each month and then issues the monthly balance for Fun, Family, and Community as a prepaid debit card. The NEC Line posts 4/15ths of the annual total in January and 1/15th in all other months for all passengers. We may have to do some juggling on timing of spending. We may spend more in a month to pay in advance for travel for a side trip at an upcoming port of call, for example. But since we get more than 25% of the annual total in January the balance of our account at the start of each subsequent month is always high.

When we want to do something fun, we just present the debit card. We never have to sign. Our Line doesn’t post the daily totals for our spending. We get the total amount we’ve spent on FFC for the month on the date than our new amount of Cruise Currency is added to our debit card. We get an electronic statement and can review the spending detail, but passengers find that using the card ensures our spending is accurate. We almost always see more added for FFC to our account than is subtracted.

The rule at NEC is that you DON’T get to keep any unspent Cruise Currency that’s available at the end of the year! You have to spend (or gift) it all in the year. Any left on December 31 is GONE.

This is quite a shift in thinking for new passengers. For years they’ve been in the mode to “Save, Save, and Invest for the Future”. They suppressed spending for Fun to have more in the future. Now’s the time to cash in: it’s “Spend (and gift) for More Fun NOW”: saving now doesn’t really result in more to spend on FFC later.

Passengers get used to this change in time. At the start of every year they enthusiastically discuss their plans to ENJOY NOW with their family and other passengers. Most spend for Fun to their heart’s content – within reason, obviously – for the first nine or so months of the year.

Then they shift to figure what might be available to gift to their family or to favored charities before the end of the year. Passengers report in customer satisfaction surveys that this is a most satisfying aspect of the NEC Line. (Cruise Currency for family and charities – landlubbers – is converted back to their currency.)

== Margie misses two keys ==

I keep thinking about Margie in last week’s post. This still bugs me. She has plenty of money for a fabulous cruise and lots of Fun, but she still worries about money – her spending – EVERY DAY. She’s put herself in the position to have to decide when she “needs” money; she goes through a tortuous process with her investment advisor to get money from her nest egg. She feels guilty every time she does that. This is NO WAY to spend one’s retirement.

Two key decisions would make all the difference in the world to her – dissolve the negative in her life (worry); get focused on the positive (spending for FFC). They’ll make all the difference in the world to you if you do both.

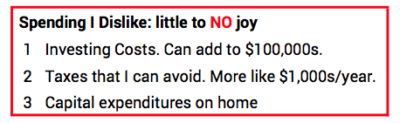

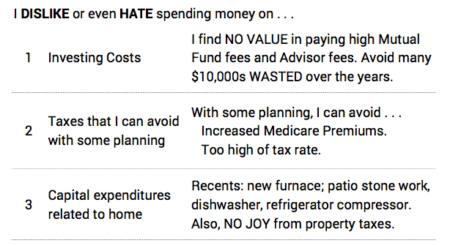

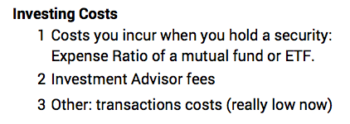

1. Figure out what’s safe to spend from her nest egg. It’s not hard to calculate this amount; I obviously know where to look to get the answer quickly (Appendix G, Nest Egg Care). (Note: this calculation assumes a lower Investing Cost than Margie incurs now.)

2. Pay herself a monthly amount– a direct transfer from her investment account to her checking account – in a pattern that means her checkbook is always – or almost always – flush with cash. I recommended 4/15th in January followed by 1/15th in all other months. That should do it.

Conclusion. We should think of our retirement as an extensive, all-expenses-paid cruise. We need to make a basic decision as to what’s safe to spend from our nest egg. The Nest Egg Care Cruise Line has a workbook that gets you to that decision. We also need to lessen the pain of spending money at this stage of life: don’t go through a thought process of whether or not you “need” money to spend: just pay out your total in the year in monthly amounts that keeps your checkbook balance healthy. Focus on what’s Fun to do. The sands of time are running.