Can you pull the trigger to sell a sick actively-managed fund to then buy an index fund?

Posted on April 24, 2020

Let’s assume you followed last week’s post and found you have a couple of stock funds – or even stocks– in your taxable account that just aren’t performing. How do you decide to pull the trigger to sell and take the net proceeds and buy an index fund? You’ll pay tax now and have less to invest. But you’re pretty sure you’d make some of that up with higher future return from the index fund. The central question is, “How long does it take to make up the difference such that I’ll have more in the future?” The purpose of this post is to help you make this decision. In summary, you’ll find that it doesn’t take very long at all to come out ahead with the index fund. Pull that trigger.

Just to be clear. We’re talking about funds – or stocks – you have in your taxable account. It’s easy to pull the trigger in your retirement account: taxes don’t figure into the equation. If you are following the plan in Nest Egg Care (NEC), you sold all your actively managed funds and stocks a while back, and you just have two stock funds and two bond funds in your retirement accounts. (See Chapter 11, NEC.)

== Inertia not to act: fear of taxes ==

Most folks hang on to actively managed funds in their taxable accounts that they don’t really like because they HATE the idea of selling and paying capital gains taxes now. Hey, I HATE paying taxes, too.

Some folks I know think they should NEVER SELL a sick fund or stock. Their thought is to hang on for the rest of their life (or lives if a couple) to avoid paying capital gains taxes: when they die their heirs inherit the fund; their new cost basis is the value on your date of death. You avoid capital gains taxes in your lifetime(s); heirs don’t pay tax on your accumulated gain. NOTHING can be better than NEVER paying gains taxes! You must come out ahead on this, right? NO! This is faulty logic.

This is analogous to my friend Roy, who I mentioned in this post. His accountant advised him to hold on to his rental property until he dies so he and heirs never pay gains taxes. But he’d be much better OFF to sell now, pay the taxes, and put the net proceeds in a stock index fund. It’s basically the same logic for this case of selling a sick stock fund and buying an index fund.

== The critical assumption ==

The critical assumption is that you ultimately will sell the fund – or stock – you have sometime in your lifetime. Why? I assume you’ve decided to pay yourself your annual Safe Spending Amount (SSA; see NEC, Chapter 2). Your SSA is always greater than your RMD. You therefore annually will always sell securities from your taxable account to get cash for your spending; those sales are always lower in tax cost than the alternative of taking more from your retirement accounts.

The math works out that year after year you will take a bigger share from your taxable account than your retirement accounts. Over time you’re taking an even bigger share from your taxable account. Patti and I have seen this: much less of our total is in our taxable account than in our retirement accounts. When we are in our 80s, almost all our financial assets will be in retirement accounts. If we live to our life expectancies, we’ll have very little in out taxable account.

This assumption makes the focus on your future after-tax return. You pay taxes now when you sell or you will pay taxes later when you sell. You lose potential growth because of the taxes you pay now, but you make that up over time assuming your return rate is higher from the index fund you will buy. The question becomes, “How long is that time?”

== Should Jay sell FMIHX now? ==

Spoiler alert: YEP. And others.

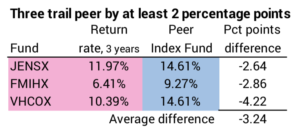

Last week I ranked nine of Jay’s actively managed funds in his taxable account. I show the three stinkers below. I need to pick one as an example. Two months ago, I picked on JENSX, so I’ll use FMIHX – FMI Large Cap Investor – as the example for this post. It’s not quite the worst, but if it makes sense to sell FMIHX, it likely will make sense to sell others.

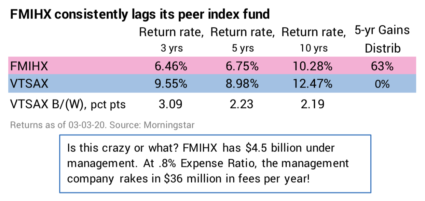

I can get more than just three years of results from the Morningstar site to double-check. The table below shows FMIHX has lagged for all time periods over the last decade. (I gathered this data in early March; I don’t have possible distortions from the recent decline.)

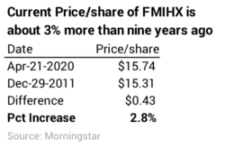

Morningstar also reports that FMIHX has had very high capital gains distributions. (You find that on the Performance page; you have to click on “Distributions” right next to “Returns”.) I talked about this penalty two weeks ago. I calculated about a .2 percentage point penalty in return per year for a typical actively managed fund. But FMIHX is not typical. It’s had unusually large capital gains distributions. They have been so large that the current price of FMIHX less than 3% more than it was in December 2011. That means Jay has paid a lot of gains taxes over the years, and his current cost basis must close to the current price. Jay records little gain if he sells now and will pay very little gains taxes.

== Jay’s inputs to the decision ===

Jay has to find one fact and make one assumption to make his decision of whether or not to sell FMIHX and take the net proceeds to buy its peer index fund. He plugs two basic numbers in the spreadsheet you can download here, and he will find how long it takes to come out ahead with the index fund.

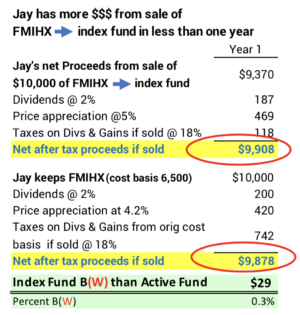

1. Jay needs to find his cost basis/share. Jay’s held FMIHX for over a decade. His cost basis is less than the current price. For this example I’ll assume that Jay’s cost basis is 65% of the current price. Because of the gains distributions, I’d guess it’s at least 90% though.

2. Jay needs to plug in his assumption of the deficit in return if he sticks with FMIHX. I look at past performance and could easily conclude that FMIHX will continue to under-perform its peer index fund by two percentage points per year.

I’ll be very generous to FMIHX: I’ll assume its future performance lags its peer index fund by .8% per year, which is just about the difference in its expense ratio between the two. That means I’m not penalizing FMIHX for its consistently poor record of stock-picking. I’ll also set its future capital gains distribution to zero percent. These assumptions seem ridiculously conservative to me.

Here are the summary results from the spreadsheet with those two inputs and tax rates Jay pays: Jay comes out ahead on this transaction in less than one year! And the advantage of holding the index fund grows year after year. The improvement in growth outweighs the penalty of paying taxes earlier. Jay, SELL FMIHX NOW and buy a Total Market Index fund like VTSAX or FSKAX* or an ETF like VTI or ITOT. Also sell the other two sick funds – JENSX and VCHOX. (*Patti and I own FSKAX.)

== Rules of Thumb ==

When you input different assumptions in the spreadsheet, you will find different break-even periods. Unless your cost basis is very low, I conclude the time to break-even from the index funds is short. I suggest these rules of thumb:

• If you think your active fund will under-perform its peer index fund by one percentage point per year, sell it NOW and buy the peer index fund.

• If you think your active fund will under-perform by one-half percentage point per year, you have little reason to keep it. I would sell TWEIX and FCNTX, for example. (See last week’s post for their expense ratio and performance.)

I would alter this advice for three actions you may prefer. 1) If you know you will be selling from your taxable account for your spending in the next year or so, just wait and sell the stinkers first. 2) Gift these funds to an person who does not pay capital gains taxes; that’s someone who is in the 12% marginal tax bracket; have them sell it and buy the index fund. 3) Donate these shares to charity; you don’t pay gains taxes; depending on other itemized deductions, you may some or most of the full market value of the donation as a deduction from income. It’s simpler for you and the ultimate charity or charities if you first donate to a Donor Advised Fund. I think the largest of these are at Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard.

Conclusion: You need to find one fact and make one assumption to decide to sell an actively managed fund in your taxable account and then buy an index fund with net proceeds. You need to know your cost basis/share as a percentage of the current price/share. You need to estimate the deficit in future return from your current fund relative to its peer index fund. This post provides a spreadsheet to help you find when you would come out ahead with an index fund. Generally, the time is very short. It was less than one year in the example used in this post.