What’s it all about now that we are retired? Enjoying More, NOW and helping others to Enjoy More, NOW. Why would we spend money on something that subtracts from what we could ENJOY?

Every year at this time I ask the question when two bills roll in, “Why don’t I use my home equity line of credit to pay our property taxes and home owners insurance and therefore provide more for us to ENJOY?” My point of this post: you should also ask yourself this question. Here’s what’s running through my head.

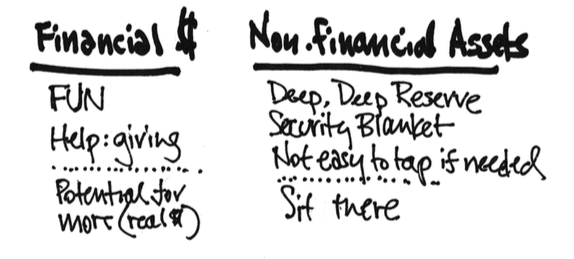

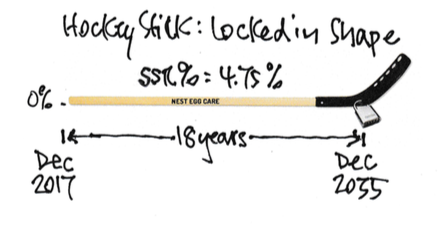

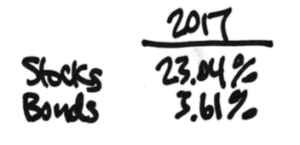

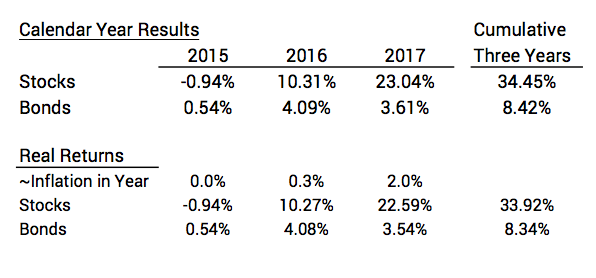

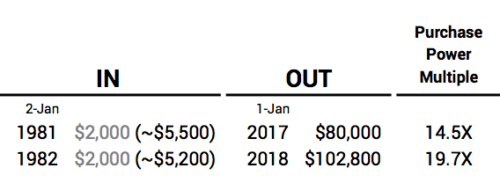

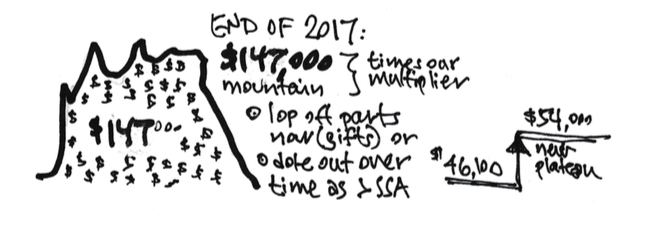

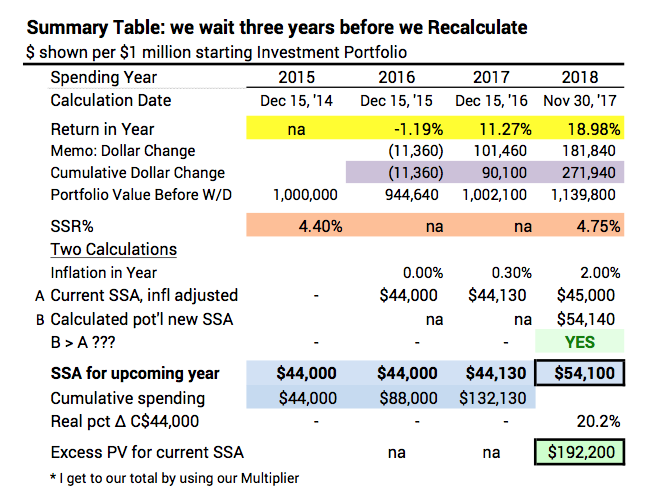

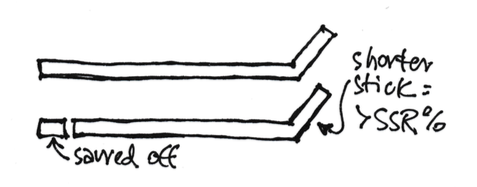

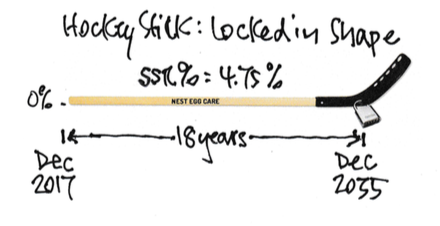

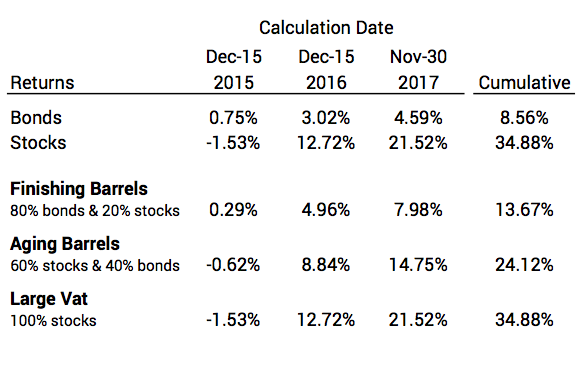

We retirees have financial assets and non-financial assets. Our financial assets are in our main fuel tank for our journey. We take out an annual amount – our Safe Spending Amount (SSA) – for our feeder tank for the upcoming year. Patti and I started our journey at 4.40% as our Safe Spending Rate (SSR%) for our spending for 2015. It’s now 4.75% for 2018. When we recalculated this past December, we also had more in our main tank than we did at the start. The multiplication worked out to a healthy increase in our SSA. Still, 4.75% is not a big flow rate. We need to put our SSA to maximum use.

Nest Eggers don’t count non-financial assets as part of our main fuel tank. Our non-financial assets are an important DEEP reserve apart from the formal financial reserve I recommend in Nest Egg Care. For Patti and me, our home is our large non-financial asset, and we love it. But its non-financial value isn’t on the same scale as our financial assets, which we clearly use (spend) to ENJOY.

Our non-financial assets basically just sit there. They’re likely to maintain their value with inflation (house yes; other no). Yes, our home in particular feels like a thick security blanket. But over the next 15 or more years we hope to be here, it’s +95% probable that our financial assets will grow faster than inflation. (At average return rates money invested in stocks will more than double in purchasing power.) Relatively speaking, our non-financial assets are a loser.

Every year at about this time I get my property taxes and homeowners insurance bills, and I stare at them. I ask, “Why am I using my FUN money to pay these NOT-FUN bills?” They’re adding no real value to our home. I’m not repairing something that should be repaired. I’m not improving the quality of living in it.

This NON-FUN expenditure can be a real drain on FUN money. I mention my friend Alice in Nest Egg Care. Let’s assume her nest egg (after the formal off-the-top reserve) was $900,000 at the end of 2017 and her SSR% is 5.3% for 2018. She will pay herself about $48,000 as her SSA in 2018.

What’s that mean? She has Social Security (maybe $30,000 net for the year) and the $48,000. Total $78,000. Let’s assume income taxes (definitely a NOT FUN expenditure) are $12,000. Net to ENJOY = $66,000.

Now let’s assume she has to spend $8,000 for NOT FUN on property taxes (high here in Pittsburgh) and on homeowners insurance. That $8,000 is more than 12% of her net to ENJOY.

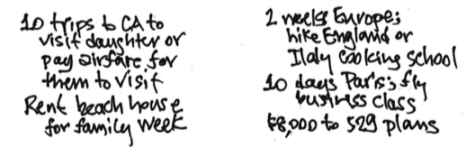

I’d think really hard about this option: pay the $8,000 out of her home equity line of credit at interest only. That would be about $25/month. (Yes, no longer tax deductible.) She’d never miss that. But how much enjoyment could $8,000 buy in 2018? Here are some options:

Alice could think, “I’d really like to rent a beach house this summer to spend a week with my son, his, wife and my two grandchildren. The whole vacation will cost $8,000, but I’ll defer. I’ll pay that $8,000 instead for for property taxes and insurance.” She could think that way every year in the future. That does not make sense to me. Enjoy NOW. Rent the beach house. Spend that special time with your family. Pay the $25/month.

Knock on wood: we all will find we aren’t riding a WORST case of future financial returns. Recalculation will show (as it did for Patti and me in 2016 and 2017) that Alice has More-Than-Enough (again) for her current spending. She can chose to repay the $8,000 or increase her SSA: the $25/month will disappear or really be trivial. That week at the beach house: priceless.

Conclusion: We Nest Eggers work hard to Enjoy More NOW for the the time left in our journey. The annual amount we spend to Enjoy comes from our financial assets and Social Security. (Some of us may have other income.) Most all of us have significant non-financial assets. Our home is a large one that consumes cash (property taxes and home owners insurance) that doesn’t really add to its value. Is the better alternative to pay those taxes/insurance by using your home equity line of credit? That would mean more joy from your Safe Spending Amount. It’s your decision: I’d lean to Enjoy More NOW.