What’s the effective capital gains tax rate? Isn’t it really more than 15%?

Posted on June 11, 2021

The capital gains tax rate is really is more than 15%, because the calculation of gain does not adjust your cost basis for inflation. When you pay tax on capital gains, you are paying tax on the real component of gain and on the inflation component of gain. How much are we hurt by paying tax on inflation? In this post I conclude that the federal tax rate on the real component of capital gains is about 19%. Over time, this effective rate declines.

== Ordinary tax brackets and inflation ==

You pay tax once on ordinary income – wages, interest and withdrawals from your traditional IRA as key examples – for your spending or for money that you save and invest in your taxable account. Income tax brackets adjust for inflation. If you earn the same real amount of dollars, you won’t be pushed into a higher marginal tax bracket; you aren’t paying more real tax just because of inflation.

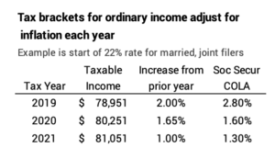

For example, the start of the 22% tax bracket for 2021 for married joint filers is about $81,050, and it was $80,250 for 2020. The IRS announces these changes to the start of tax brackets every November. The IRS uses a different method for inflation than used for Social Security’s Cost-of-Living-Adjustment for gross benefits, and the IRS’s percentage change for tax brackets is less.

== It didn’t used to be this way ==

I’m old enough to remember that the tax brackets for ordinary income did not adjust for inflation for many years: Patti and I would get pay increases that might not total to more than the percentage that inflation increased. But because tax brackets did not adjust for inflation, more of our income would be taxed at a higher marginal tax rate. Inflation, not real increases in our earnings, simply pushed more and more of our income into higher tax brackets.

The IRS took a greater percentage of income from all taxpayers prior to 1977 without real increases in their earnings, leaving them all with less real spending power. This is NOT A GOOD THING, and I think this decline in real spending power for families factored into this period of the most horrible sequence of stock returns in history.

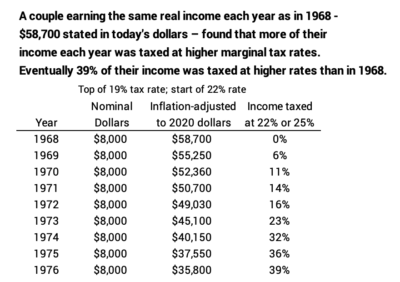

Here’s an example: A couple who earned the right at the top of the 19% tax bracket in 1968 and earned that same real amount for the next nine years found that about 40% of their income was taxed at 22% or 25% marginal rates in 1976. (See here for history of tax brackets.)

Here’s the detail: our couple had $8,000 in taxable income in 1968, right at the top of the 19% marginal tax bracket. I restate the $8,000 in 1968 to $58,700 spending power last December. Assume our couple earned that same real amount, $58,700 each year. The top of the 19% tax bracket did not adjust for inflation; it was really lower year after year. By 1976, the start of the top of the 19% bracket had fallen 39% in real spending power to $35,800 in today’s dollars – 45% of what it is today. Taxes were unfair and high!

== Capital gains don’t adjust for inflation ==

I’m sure you’ve got this: you paid income tax once to get the money that you invested in a mutual fund, ETF or stock. You pay tax on the gains when you sell for your spending. When you calculate your gain, amount you paid for an investment does not adjust for inflation. Your gain therefore includes two components: the real return component and the inflation component. You’re paying tax on both.

How much is the penalty of paying tax on inflation? Is it as bad as it was for wage earners in the late 60s and early 70s?

== My conclusion: you’re paying perhaps 19% not 15% ==

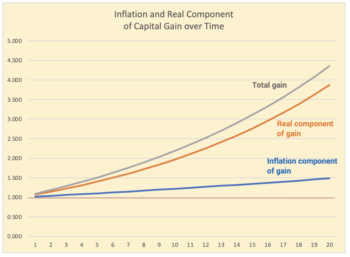

I think I’ve thought this through correctly. I use a simple example of a stock with no dividends, 7% real return from increase in price, and 2% inflation. I’ll assume those add to 9% nominal total return per year. That means 2/9 of your total gain is inflation; you are paying 29% more (2/7) than you would if there were no inflation or if your cost basis was adjusted for inflation. In effect, you are paying 19% rate on your real return.

The effect of inflation on your real tax rate is smaller with longer holding periods. You are paying less than 29% more over time. That’s because 2% inflation compounds more slowly than the 7% real. Inflation is a smaller portion of total gain. You are paying less than 19% tax rate on your real return over time.

I played with the inputs to the table to see how that 19% rate changes: lower inflation lowers the effective tax rate: inflation has averaged about 1.7% over the past ten years. If inflation is more than 2% in the future, the effective tax rate will be higher. If your real return rate is lower, inflation becomes a larger percentage of the total and the effective tax rate is higher. But as I play with the numbers, you have to assume extremes – lousy real returns or very high inflation, as examples – to move very far off the generalization that your effective federal tax rate on the real component of capital gains is roughly 19%.

Conclusion: The calculation of capital gains tax does not adjust your cost basis for inflation. You are paying tax on the real component of gain and an inflation component of gain. You are paying more than the 15% rate you’d pay if there was no inflation. I calculate in this post that you are paying roughly 19% on your real return.