How will the SECURE Act affect your financial retirement plan?

Posted on February 7, 2020

The SECURE Act, passed in December, brought changes to retirement plans –– and more will come in 2021. This post discusses the SECURE Act and what I think it may mean for you. Next week I’ll describe lower RMD percentages that start in 2021.

== SECURE Act passed December 2019 ==

You can find summaries of this Act. Two are here and here. I highlight two key changes that affect retirees or those nearly retired.*

1. You don’t have to start taking withdrawals until the year you turn 72 (up from 70½).

2. Heirs after your death – with some exceptions – have to withdraw from their inherited IRA within ten years; that could have easily been over 30 or more years before. A key exception is a surviving spouse: SECURE did not change the RMD period or percentages.

How significant are these two?

== Two years of no RMD ==

What’s the benefit of not taking RMD at age 70½? This does not apply to Patti and me. We both take RMD now, but those younger may see a benefit from not taking RMD for two years.

• The first benefit is lower immediate taxes on the amount you withdraw from your nest egg for spending. If you don’t withdraw from your IRAs or 401ks for two years you’ll withdraw from your taxable assets. You always have the incentive to withdraw more from your taxable assets than from your IRAs. That’s due to the difference in effective capital gains tax rates and income tax rates. In this example your effective capital gains tax is about 1/3 that of income tax. You net 19% more to spend when you get your cash from the sale of securities in your taxable account.

This advantage of lower taxes on withdrawals from your nest egg dissipates as you get older. You will shift to a greater portion of your withdrawals coming from your IRAs.

– Your Safe Spending Rate (SSR%; see Chapter 2, Nest Egg Care) is always more than your RMD percentage. When you start out on your retirement plan, you withdraw your total SSR% and Safe Spending Amount (SSA) but you (generally) don’t withdraw more than RMD from your retirement plans. You therefore are always disproportionately withdrawing from your taxable account.

– You’re lowering your taxable assets, your lowest tax-cost source for cash for spending faster than you are lowering your IRAs. Year by year you inch toward the point where your retirement assets are a much greater part of your total. (Patti and I are that point now.) Then you’ll withdraw disproportionately from your retirement assets. The total tax bite out of your total withdrawal with be greater; your net to spend for a given withdrawal will be less than before.

That’s not a problem in my mind. Patti and I have seen a 22% real increase in our SSA over the past five years and even with modest returns this year we’ll see another real increase for spending in 2021. (All nest eggers have seen a significant real increase in their SSA.) Even after paying a greater percentage in taxes when we’re in our late 70s or 80s, we’ll have a greater net to spend than when we started our plan in 2015. And Patti and I both think we will spend less when we are in our 80s.

• You have a second benefit. As I mentioned in this post, when you keep money in your IRA you get a tax-free ride on the growth of your investment: you’re avoiding capital gains tax on the growth of your investment. You’ll have greater portfolio value later. That’s a good thing.

How much is this benefit? It’s good but not spectacular: $10,000 that has a 6% expected real return rate (a combination of 7.1% for stocks and 2.3% for bonds) would grow by about $8,000 in a decade. You keep all of that tax-free growth when you then withdraw from your IRA for your spending.

If that $10,000 was in a taxable account you’d be paying 15% federal capital gains tax. A simple way to look at this is to assume that capital gains tax is 15% of $600 of annual grown. That’s $90. While this simple example doesn’t count the effect of compound growth, I think that $90 close enough to get the picture. You come out ahead by $90 per year for each $10,000 you choose to leave in your IRA. That’s nice, but certainly does not change your financial future in any significant way.

== It’s possible to wipe out the benefit of tax-free growth ==

That math that calculates the benefit of tax-free growth assumes the marginal rate you would pay if you withdrew now is the same one that you’ll pay when you withdraw in the future. That may not be the case. I describe the possibility of being taxed at a higher marginal tax rate in this post: at expected return rates for stocks and bonds, your RMD will increase over time and will double in real spending power in about a dozen years relative to a withdrawal at age 70½. You are always being pushed toward a higher marginal tax bracket.

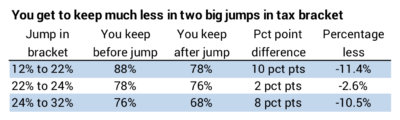

That doubling could put a portion of your total income in a much higher marginal tax rate than the one you experience at age 70½. You get to keep far less when you cross two big jumps in marginal tax in our current tax code: 12% to 22% and 24% to 32%. The higher bracket takes about a 10% bite out of the net you get to keep than the lower bracket. Cross one of those jump points and you start to lose all or more than all the benefit of tax-free growth.

It’s a bit of work to figure out if you might cross a jump point. (The post describes steps to figure this out.) This is particularly worth figuring out if you are a married couple with sizeable Traditional IRA (over $2.5 million) when you first start to take RMD. The example in the post showed a married couple would never get close to the 32% tax bracket, but when one dies 20% of the income of the surviving spouse would be taxed at 32%.

== The impact of ten-year rule on heirs ==

The ten-year rule on withdrawals for heirs will have an impact on the after-tax benefit they receive: withdrawals may put them in a much higher marginal tax bracket than they would otherwise experience for the prior “stretch IRAs” that could run for decades. Some writers have gone nuts about this, describing this as “a confiscatory death tax”. I discussed this issue last summer in this post. I don’t see this as a big issue:

• The “stretch IRA” rules were not rational in my mind. The thought that my Traditional IRA contribution in 1981 could have some part compound tax-free for decades – even eight decades – after I die is almost ridiculous. I don’t think folks thought that through when they wrote the legislation that set those rules for an inherited IRA.

• I argue that the “stretch IRA” similarly pushes your heirs to higher marginal tax rates for the same reasons that you are pushed toward a higher marginal tax bracket. RMDs will increase in real terms. That “confiscatory death tax” is a red herring. Heirs very well could pay in the same high marginal tax bracket under the “stretch IRA” as under the 10-year rule.

• If Patti and I left money from our IRAs to our heirs (We don’t plan to leave all of our IRAs to them; we think it’s better is to leave our IRAs, never taxed, to charity.), we’d want them to enjoy it earlier in life and not leave most of it untouched for their retirement decades later. We’d like them to take it out within ten-years or less to improve their lives sooner rather than over perhaps 45-years.

Conclusion: The SECURE Act, passed this past December, changed the rules for retirement plans. The two most significant changes for retirees or those soon to retire are 1) Required minimum Distributions (RMDs) begin in the year you turn 72, not 70½; and 2) inherited IRA distributions generally must now be taken within 10 years. I personally don’t see that much advantage to waiting to take distributions from your IRA. I don’t get upset about this.

* I ignore one change that seems insignificant to me: you can now contribute to a traditional IRA beyond age 70½. This just aligns Traditional IRAs with Roth or 401ks; you could always contribute to those two beyond age 70½ if you were still working. Note: there is no special advantage to contributing to a Traditional IRA relative to a Roth IRA; if the tax brackets at time of contribution and at the time of withdrawal are the same, Traditional and Roth result in the same after-tax dollars to you.)