What are the costs of holding Active funds?

Posted on March 10, 2023

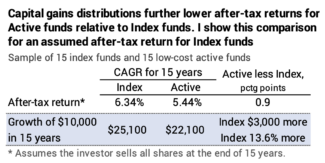

I liked this article, “Index Funds’ True Advantages.” The author took a sample of 15 Index Funds and 15 low-cost Active funds and compared them over 15 years. While this is a very small sample – much smaller than the universe of funds examined here – the comparison reinforced the two penalties from holding Active funds rather than Index funds. 1) The returns from Index funds are greater than Active funds by the difference in their costs: their expense ratio. 2) Active funds return less than Index funds on an after-tax basis because of early taxes paid on capital gains distributions. In the example, Investors lost about 1/2% of annual after-tax return from the two factors.

== Index funds return more because of their lower cost ==

As I mention in Chapter 6 Nest Egg Care, in a simple world of just Index funds and Active funds, the fundamental math says that, in aggregate, Index funds and Active funds earn the same market returns before costs That’s a zero-sum game.

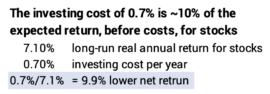

One has to subtract investing costs – at least a fund’s expense ratio and advisor fees, if any – from market returns to get the net to an investor. The simple story is that cost for Index funds is close to 0%, but the average for active funds is about 0.7% per year; the typical Active fund will return 0.7% less to its shareholders per year. At expected returns for stocks, these investors earn ~10% less return per year than Index fund investors.

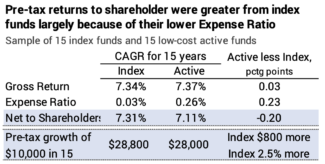

This is essentially what happened in the sample of 15 Index funds and 15 Active funds. The Active funds in the sample had VERY LOW expense ratio, about 1/3rd that of the average Active fund. Still, they could not overcome their added cost. Before expenses, the sample of Active fund returned slightly more than the index funds – 0.03% per year; that meant this sample of 15 beat other Active funds by a whisker. But expenses were 0.23% more per year. Index funds returned 0.20% more per year. On a pre-tax basis – if the funds were held in a retirement account – shareholders of Index funds would have about 3% more after 15 years.

== Capital gains distributions lower after-tax returns ==

A mutual fund passes its taxable gains from the sales of securities onto its shareholders as a Capital Gains Distribution. If the investor holds the fund in a taxable account, he pays the tax, not the fund. This discussion does not apply to a fund in a tax deferred account; there is no adverse effect of capital gains distributions.

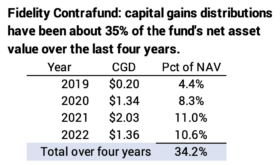

An Index fund basically buys and holds and RARELY has a gains distribution. An Active fund trades shares to reshape its portfolio in its attempt to outperform other Active funds. An Active fund might completely change or turnover 20% of its holdings in a year. Some Active funds issue Capital Gains Distributions annually. Fidelity Contrafund, the largest Active fund, has distributed nearly 35% of its Net Asset Value as Capital Gains Distributions over the last four years.

The fund’s shareholders receive no added cash, and the total value of their holding remains the same after the distribution. They get more shares, but the Net Asset Value per share declines. The shareholder’s cost basis increases by the amount of the distribution. When the shareholder finally sells to get cash for spending, the capital gain and tax are less. But the shareholder’s after-tax return is less than if they never had a capital gains distribution. They have lost some after-tax growth by paying taxes earlier than they otherwise would.

In this post, I calculated the amount lost in annual after-tax return is roughly 0.2% in annual return relative to an index fund. This is a good rule of thumb. The percentage varies by perhaps less than 0.1 percentage point depending on the amount and timing of distributions and the number of years you hold the fund before you sell it for your spending. (This penalty is roughly double for someone who holds on to an active fund in a taxable account to death and therefore would never incur a final capital gains tax.)

The 15/15 sample basically confirmed this rule of thumb. It found the total after-tax penalty from Active funds was 0.46% per year: that’s roughly 0.20% from lower pre-tax return from their greater costs and 0.26% from the effect of paying taxes too early on capital gains distributions.

== Maybe 15% more ==

If the average Active fund is 0.7% greater in cost and has 0.2% penalty from Capital Gains Distributions, the average Active fund in a taxable accout is earning 0.9 percentage point lower after-tax return. That difference accumulates to about 14% more from index funds in 15 years, and the difference is greater with more years.

Conclusion: Active funds have two costs to their shareholders. In aggregate the funds will return less to investors by their expense ratio, which averaged 0.7% in 2021. They also pass on capital gains distributions from their sales of securities onto shareholders; the gains are taxable without increasing the investor’s value; paying taxes earlier lowers the after-tax return by about 0.2% per year.

A recent article in Morningstar supports these two facts using the results of a small sample of 15 index funds and 15 active funds for 15 years. Active funds had 0.23% greater expense ratio and underperformed Index funds by 0.20% per year on a pre-tax basis. On an after-tax basis, which includes the effect of capital gains distributions, Active funds underperformed by 0.46% per year.

Index funds. Not Active funds. You’ll have more pre-tax in the future. You’ll have even more in a taxable account since you avoid the effect of lower return from paying taxes early from capital gains distributions. Sell your active funds in your taxable account for your spending before your index funds.