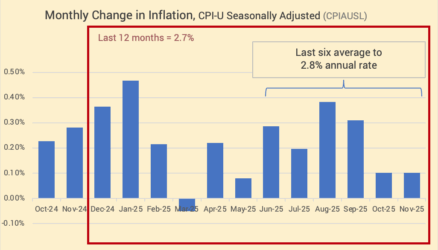

Popular press reports and indicators of value like the Shiller’s analysis of P/E ratios say the US stock market is way overvalued. Some experts are predicting a crash due to massive government debt, over-hyped AI expectations, Trump’s tariffs and trouble in the lending markets. We aren’t even getting a good picture of how our economy is doing with the government shutdown.

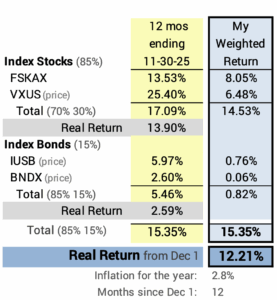

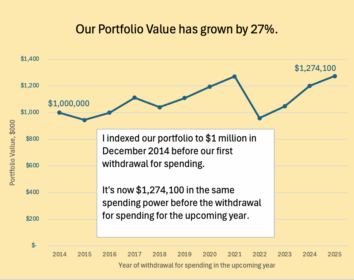

The market has boomed the last three years: US stocks are up more than 66% from the -18% real decline in 2022. You have more money now than you’ve ever had in your life. What should you do?

== Here’s what I did ==

I’m sticking with the plan. If a storm comes, I will ride it out. I have no risk of depleting our portfolio. But I took some “profits” now.

1. I sold securities at the start of this week for our QCD donations that are part of our RMD and tax plan. In the past, I’ve sold for QCD on December 1. I thought it prudent to sell now. I can cut the QCD checks now. I can mark that off my checklist of December tasks.

2. I “pre-rebalanced” our portfolio. I dislike that rebalancing task each December. In most years, when stocks far outpace bonds, I only sell stocks for our spending and then I sell more stocks to buy more bonds to get to 15% bonds. I grind my teeth on that second sale (or exchange from stocks to bonds). We’ll all be faced with two sales of stocks again this year, since stocks most likely will be far greater in return than bonds.

I calculated our mix over the weekend and found that I’ve been sloppy: I did not get enough in bonds last December. That error “cost us” (Patti and me) more portfolio value than we would otherwise have (Oh, the Shame), but we don’t have the proper level of insurance. This was a good time to clean up my sloppiness and hit my design mix of 15% bonds. (I may have to tweak in December.)

(I did not grind my teeth when I did this! Maybe I should consider separating this step from my sales in December for our spending for the upcoming year.)

= Four years ==

My design mix of 85% stocks and 15% bonds means I don’t have to sell a significant amount of stocks for more than four years. I’ll sell about 5% from our portfolio this December and have that in money market for our spending in 2026. The 15% that I have now in bonds is three years of spending: I can avoid selling stocks in December 2026, 2027 and 2028.

My first sale of stocks would be December 2029, and I wouldn’t have to sell that much then. I could sell the amount that I would sell stocks to withhold for taxes for 2030 and transfer the rest of our RMD as shares from our traditional IRAs to our taxable account. I would sell shares throughout 2030 for the monthly “paychecks” – transfers from our Fidelity brokerage account to our checking account. (I used this tactic for our spending in 2024.)

== Is that enough? It’s a judgment call. ==

Four years is a good cushion in my mind. I wouldn’t want fewer years. The worst would be a repeat of 2000, 2001, and 2002 in mind: US stocks declined 42% in real spending power those three years. Those three years burst the “Dot-com bubble” of the late 1990s.

If I sold in December 1999 for spending in 2000 and then had 15% in bonds, I would have been able to delay selling stocks until December 2004 and pushed most sales into 2005. Stocks rebounded in 2024 with +23% real return. That didn’t get all the way back, but that delay in selling would have been much less damaging to our portfolio.

== What I did not do ==

I did not consider permanently changing my design mix of S vs. B. That’s not a good way to lower the chances of depleting a portfolio. The far better tactic is to spend a little less from your portfolio.

The probability of depleting a portfolio for a given constant-dollar spending amount looks like a hockey stick: your spending rate locks in the number of years of Zero Chance of depletion (the shaft of the hockey stick); you have a rising probability of depleting the years after that point (the blade of the hockey stick). (See Chapter 2, Nest Egg Care [NEC]).

You extend the length of the shaft when you are retired – gain more Zero-Chance years – by spending a bit less. Not by lowering your mix of stocks. (See Chapter 8, NEC.)

Selling just 5% less – that would be 4.75% and not 5% in our case – at 85% S has the same effect on shaft length and blade angle as shifting mix to 60% S. (Graph 8-1 in NEC). But, boy, that can be costly: the table below shows you give up $500,000 in future portfolio value (assuming $1 million start) in 20 or so years if you ride a normal and not Most Harmful sequence of returns. You would always choose to spend $2,200 less per year for 20 years in return for expected result of $500,000.

== Good stewardship for our heirs ==

At our age (I’m 80), we’re not investing just for ourselves. We’re at least partially investing for our heirs. They should be 100% in stocks at their age. Good stewards of the amount they will inherit will have a high mix of stocks but just spend a little less than they could from a lower mix of stocks.

Conclusion. The pundits think the stock market is way over valued and primed for a big correction. They may be right. What should you do?

I plan to stick with the basic plan. I’m basically going to ride out whatever comes as I have for all my life. I sold stocks now for our QCD that is part of our tax plan for 2025. I “pre-rebalanced” our portfolio to make sure I had my target of 15% in bonds now. When I sell in December for our spending for 2026, I’ll have four years in money market or bonds. I like that.

I definitely am not going to change my design mix – e.g., lower it to 60% stocks – because I’m older or because I think that is a way to lower the chances of outliving our portfolio. A greater mix of bonds is a weak lever to lengthen the number years of Zero Chance of depletion year. A greater mix of bonds means you’ll have MUCH LOWER portfolio value when the future sequence of returns is other than worst case. The lever for more Zero-Chance years is to spend a little less.