I fiddled with my bonds. Should you?

Posted on September 17, 2021

For many years I fiddled annually with my stock portfolio. Decades ago, I would spend hours and hours trying to pick winning stocks. Years ago, I would spend hours trying to pick winning, actively managed stock mutual funds. I stopped all fiddling for the last seven years when I started our financial retirement plan: I concluded that fiddling was adding uncertainty to my future returns: we don’t want to add more uncertain to an already uncertain future. Stick with broad based, low cost index funds. But this past month I could not resist fiddling with the ~20% of my portfolio that is bonds. Patti and I now own three US bond funds, not just one that I’ve held for more than six years. The purpose of this post is to explain my thinking.

== Bonds are insurance ==

We all hold bonds as insurance against steep declines from stocks. (I’m a broken record in saying this, but most folks just don’t get this concept.)

You get the same basic insurance value with almost any mix of broadly diversified bond fund. This post shows that both Long-term bonds and Intermediate-term bonds outperformed stocks in their ten worst years by an average of 27 percentage points. Those Horrible Years for stocks are the years when you collect on your insurance: you will disproportionately sell – or even solely sell – bonds for your spending needs. You’re giving stocks time to recover before you must sell them for your spending.

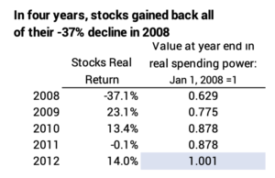

Patti and I hold 5% bonds as a Reserve and 15% in the balance that I call my Investment Portfolio (See Chapter 1, Nest Egg Care [NEC].) To simplify, I have about 20% bonds in total. Our spending rate is nearing 5% (We are older.) We have, at minimum, four years of spending as bonds. We could, if stocks cratered, live off bonds for at least four years, giving stocks four years to recover. (Patti and I could easily spend less than our current annual Safe Spending Amount [SSA; see Chapter 2, NEC] and extend those years. Our SSA now is +30% greater in real spending power than in 2015, the first spending year of our plan.)

Here’s the extreme example: Stocks declined by 37% real return in 2008. Obviously, you don’t want to sell stocks when they’ve declined that much. You would have sold your Reserve (bonds) at the end of 2008 for your spending in 2009. (Long-term bond returns were +25% real return in 2008!) At my mix, you’d have at least three more years of spending as bonds: you could sell only bonds at the end of 2009 for your spending in 2010; you could do the same at the end of 2010 and again in 2011 for your spending in 2012. Let’s assume that you’d be out of bonds, and at end of 2012 you would have to sell stocks for your spending in 2013. But by the end of 2012, stocks had clawed back all their decline. You would not have sold stocks at a value lower than their value in January 2008.

== Better returns? ==

I changed by view from this post. I decided to chase a slightly better returns from bonds:

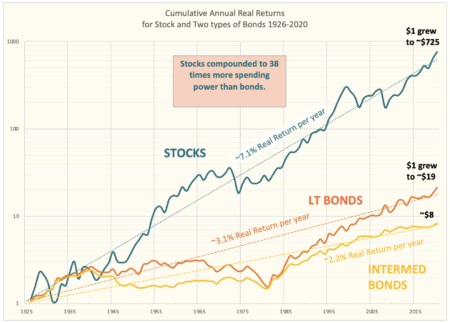

The expected return for Long-term bonds is 3.1% and it’s 2.2% for Intermediate-term bonds. My choice of total market bond fund, IUSB, and the average duration of all of its holdings (5.8 years for 9,747 different bonds!) means it’s really an Intermediate-term bond fund. Since all broadly-based bond funds have the same basic value as insurance, shouldn’t I invest more in Long-term bonds for the added expected return?

The 0.9 percentage point difference in returns cumulates to 7% more from Long-term than from Intermediate-term over the past 6.7 years. Had I invested in only Long-term bonds, I would have expected to have about 7% more bonds than I do now. That’s not peanuts for Patti and me. I should not dismiss that dollar difference for Patti and me or for those who will ultimately benefit from our portfolio.

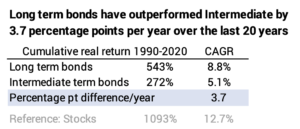

Those long run averages from 1926 both have ~45 year stretches of 0% real return. Maybe the comparison of returns shouldn’t be from 1926 to the present. Maybe I should compare returns after the nadir for bonds in the mid 1980s. I can draw a line point-to-point over the last 20 years on the graph above – from 1990 through 2020 – and see that the lines are steeper than those long-run averages. That means the annual return rates have been greater than the averages from 1926. I find that Long-term bonds have outpaced Intermediate-term bonds by an average of 3.7 percentage points per year over the past 20 years. If I assume those return rates over the past 6.7 years, I’d have about 26% more in bonds than I do now. Now were reaching a serious dollar difference.

Finally, I can compare returns for a specific Long-term bond index fund and IUSB over the past 6.7 years. I pick VCLT from the short list I displayed in this post: the ETF for Vanguard’s index funds of Long-term Corporate bonds. (Its expense ratio is .05%, a shade less than that for IUSB.) If I had solely been in VCLT, my return would have been +5% more per year on average, and I’d have about 40% more in bonds than I do now. I certainly can’t dismiss that!

No one knows what the future will bring. Prices of bonds move in the opposite direction to interest rates. Long-term bonds are more sensitive to increasing interest rates than intermediate term bonds: prices of bonds will fall more than intermediate bonds. Interest rates will increase with inflation, and inflation has increased. Is this the exact worst time to hold Long-term bonds? I don’t know. I said the heck with thinking about timing, and decided to sell some IUSB in our retirement accounts to avoid any tax consequences to hold VCLT. In essence, I’m adding more Long-term corporate bonds than IUSB already owns. Patti and I now have VCLT as 20% of our bond holdings.

== Is FBND better than IUSB? ==

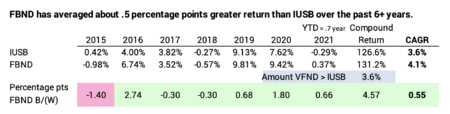

I generally DISLIKE actively managed funds. Morningstar lists funds that it judges are in the same category of “Core-Plus” total market bond funds. FBND is one I find in that prior post that has bettered IUSB over the past few years. FBND started just about the time that IUSB started, in mid-to late 2014. Its expense ratio is 0.36% compared to 0.06% for IUSB. That’s a 0.30% mountain it must climb every year just to match IUSB, but it’s beaten IUSB by an average of .5 percentage points per year over the last 6.7 years.

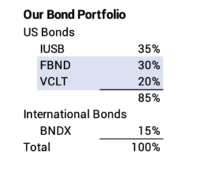

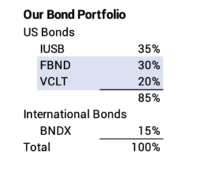

I decided to sell some IUSB, again in our retirement accounts, to buy FBND. Our total bond portfolio looks roughly like this now:

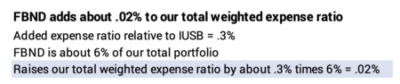

My plan is to stick with FBND for at least three years. FBND has the highest expense ratio of any fund I own, but since I own so little relative to the total (about 6% of the total), I still will have a total weighted expense ratio of less than .07%.

Conclusion: I’ve been very good about not fiddling with our portfolio. I did not make a change in more than six years. But I fiddled and added two bond funds (ETFs) to my portfolio. I added the index fund VCLT for a greater weight of Long-term bonds than I get from my Total bond fund, IUSB. I added FBND as a direct alternative to IUSB, since it has performed better over the past six or seven years. In my view, these changes do not harm the safety of my portfolio, but they may add a bit of return over time. The power of compounding tells me means that a slightly better return could add a relatively significant dollar amount over time.