I switched financial advisors this week. What was my thinking?

Posted on June 18, 2021

Several of my friends have separated from their financial advisors and became a self-reliant investor. It’s pretty simple for us nest eggers, since our total portfolio is only four index funds. I have never hired a financial advisor for our money. But I separated this week from an advisor I hired almost nine years ago for a Trust where I am trustee. In essence, I’m the Trust’s financial advisor now, and that’s the responsibility that the Trust agreement assigns to the trustee. The key advantage of the switch is that I won’t pay myself the advisory fee that I have been paying. The purpose of this post is to describe my thinking as to why I made that change: what appears now as a small, almost inconsequential advisor fee results in a MUCH SMALLER portfolio value over the very long run.

== Trust and trustee ==

Patti’s brother and his wife set up the Trust in 2006. It held option shares in a privately held company. He was CEO. I agreed that I would be trustee. It had no dollar assets. The option shares just sat there. The trust is a structured as a generation skipping trust, meaning the objective isn’t to provide money to the three children but to their children. The trust will have a very long life; it terminates on the death of the last of the three children. That’s likely more than 60 years from now: the youngest daughter is 24.

The company was sold in 2012, and the option shares turned into real money! I had to invest it. I was concerned that I might have a liability, and I wanted an advisor to provide some sort of check on my decisions. I hired a very good guy, Mike, who agreed with a low-cost index fund approach: he recommended a fairly complex portfolio that a study he cited said would outperform the market. Everyone wants to beat the market, and I bought into this in 2012. The Trust’s portfolio had a total of 13 moving parts – individual securities (ETFs). This splitting of the total market of stocks and bonds into many segments is fairly standard fare for advisors. I show the ten slices for stocks.

== Portfolio tilts and rebalancing ==

The US stock portfolio was weighted or tilted to value stocks and to mid- and small-cap stocks, for example. Over the past nine years, the exact opposite tilts would have returned more. No tilting would have returned more.

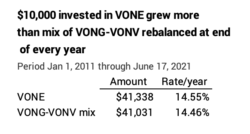

At least once a year, Mike would rebalance the portfolio to get close to the design percentages for each of the 13 securities. For example, the design mix of large-cap value (ETF = VONV) is 52% relative to 48% for large-cap growth (EFT = VONG). If VONG’s returns were greater than VONV’s, Mike would ask and I would agree that he should sell VONG and buy more VONV to bring the portfolio mix back to the original design mix. The thinking is that you want to sell when something has grown faster than its long-run average (“sell high”) to buy something that has grown slowly (“buy low”). That’s a lot of moving parts that one is trying to bring back to a design mix each year.

This approach sounds great, but in practice – ignoring the impact of paying taxes on capital gains incurred – that rebalancing tactic is no improvement over just holding the blend fund ETF = VONE that holds all the stocks held by VONV and VONG. I summarize the returns from a spreadsheet I made that tracks returns over the past +ten years. The Trust would have slightly more today if it just held VONE rather than the mix of VONV+VONG rebalanced at the end of every year.

== Capital gains taxes ==

The annual rebalancing meant that the trust incurred capital gains taxes every year: we were always selling some ETFs – and in some years a bunch of ETFs – and incurring gains just to rebalance. Those gains would be analogous to gains distributions that you can get from actively managed funds: you aren’t getting any more money from them; you are simply paying gains taxes now and not deferring the tax when you actually sell your holdings for your spending. Paying gains taxes earlier than you otherwise could lowers your ultimate after tax proceeds: I calculated in this post that this is not a big penalty – a small fraction of one percentage point per year – but it is a penalty that is not being offset from greater return.

== My liability as trustee and the fee ==

When I first thought about switching from Mike, I reread the trust agreement. I have NO personal liability as to how the money is invested or the fees charged! I think this is standard language in trusts like these: “No Trustee shall be liable for any mistake or error in the administration of the Trust which does not amount to gross negligence or willful misconduct.” I really did not need whatever I thought a financial advisor offered as liability protection.

Mike’s fee to be advisor was at the very low end of what most in the industry charge. I certainly can’t complain about the small percentage. To heck with the percentage. I kept looking at the increasing amount of the fee; it’s not a tax-deductible expense to the Trust.

Mike took on the trust account for a dollar fee that I presume made him happy in 2012. Over the +eight years, the Trust has more than doubled in value, and therefore Mike’s fee has more than doubled. Has the work effort doubled? No. Does he have some sort of greater financial responsibility now that merits a greater fee than then? I don’t think so.

I think about the effect of compound growth and fees over the lifetime of the Trust. The Rule of 72 tells us the portfolio – based on its mix of stocks and bonds – will double in today’s spending power roughly every 12 years, and therefore Mike’s fee is doubling in real spending power every 12 years. The trust will exist for 60 more years or five doublings from now – a factor of 32. Mike has one doubling of fee under his belt. Does it make sense for Mike (or his firm, since the trust will outlive me and Mike) to be eventually be paid 64 times the spending power the original fee? No.

== The right way to look at it ==

Looking at the fee is not the right way to look at it. It isn’t the amount of the fees; it’s fact that fees lower the net return rate for the portfolio. The compounding of a slightly smaller net return rate spells a big difference in portfolio value. The question is: does a small difference in return rate from the advisor fee have a significant impact on portfolio value over time? Spoiler alert: it’s HUGE given the long life of the trust.

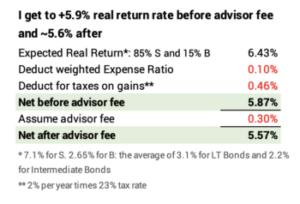

I first have to get to the expected after-tax return rate difference: it works out that I need to compare portfolio growth at ~5.9% real return per year vs. ~5.6%.

Given the mix of stocks and bonds, the expected return rate for the portfolio is ~6.4%. The ETFs have a weighted expense ratio of .1%. (That’s higher than the .04% for my portfolio, because the small segments are more costly to manage.) I’ll deduct another .5% for the annual taxes the trust will pay on dividends and interest: my simple estimate is 2% dividend rate and 23% tax rate. I get to ~5.9% return rate. Now I’ll subtract a REALLY LOW advisor fee of just .3% to get ~5.6%. I now can compare the effect of two return rates.

== It’s A BIG DIFFERENCE over the life of the Trust ==

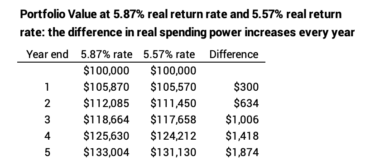

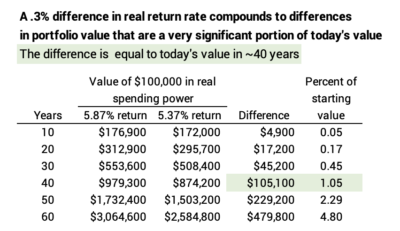

The difference in portfolio value from .3% difference return rates is almost inconsequential for many years. If the portfolio had $100,000 at the start of this year, the difference in value at the end of the year – assuming the expected return rates – is just $300 in today’s spending power: this isn’t worth worrying about. At five years the difference is $1,900; still no big deal. If the start was $100,000, I can easily overlook the cumulative $2,000 difference in value.

The difference in portfolio value keeps growing to MUCH MORE than the $2,000. In 40 years when the when the children are roughly retirement age – their children might be in their 30s – the difference in portfolio value equals today’s value in spending power. If the Trust has $100,000 today, that means there would be $100,000 less in real spending power from the advisor fee. In 50 years, it’s twice that. It’s more than four times in 60 years. It’s a HUGE difference.

= My discussion with Mike ==

I called Mike. I wanted to visit him at his office and tell him face-to-face, but he said he really wasn’t going into the office and wouldn’t go in for a while. I erred in telling him what I was thinking of doing without the preliminary of telling him what a good guy he has been over the last nine years. He was not happy with my decision, and placed a mild guilt trip on me. “Your account is one of the very best performing accounts I have. It is by far the best performing portfolio relative to other trust accounts that I have with banks as trustees.” Yep, I’m sure all that is true. But that’s not the point. The difference is portfolio value without his fee is HUGE. And my calculation ignores the effect of added gains taxes from all the rebalancing.

I think we parted on somewhat friendly terms. I followed up with a nice email of thanks after I opened the account for the trust at Fidelity. (That was a simple. The whole process to transfer all the holdings will take about five business days.)

Conclusion: If we think we are a self-reliant investor, we can invest without the aid and expense of a financial advisor. I recently decided not to use a financial advisor for a trust where I am trustee. This post discussed the basic reasons: but the simple reason is that the impact of what anyone would agree is a small advisor fee has a very outsized effect on future portfolio value. Without the fee, the trust will grow – in today’s spending power – to several added multiples of its current value.