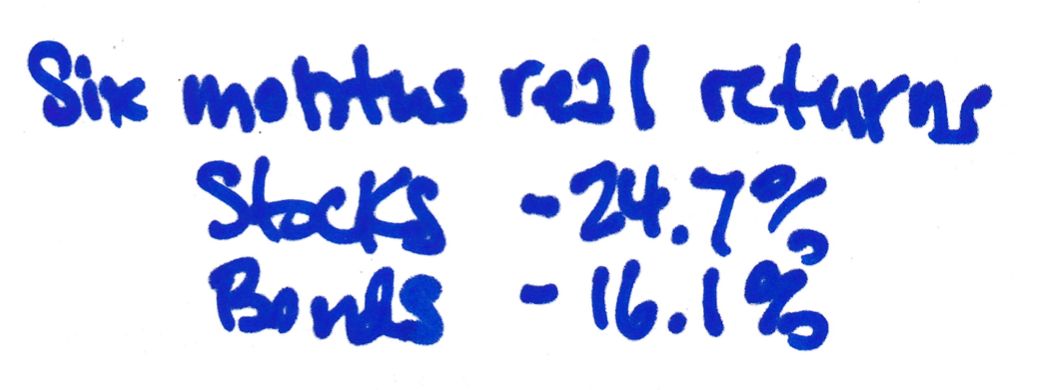

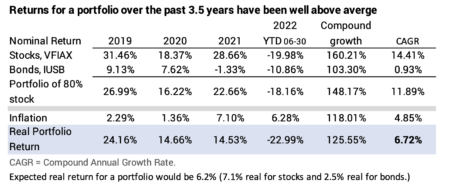

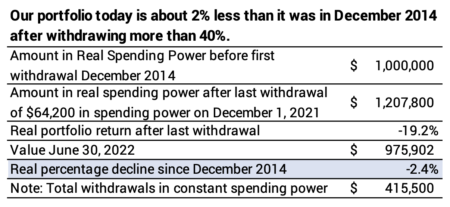

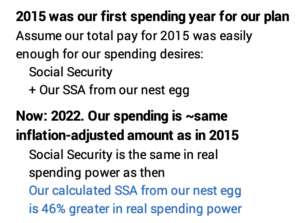

The last several posts described how you get to the number that is ENOUGH for your spending for the rest of your life or lives. See here, here, and here: after going through that math, I find that Patti and I are Happy Campers that I describe in Chapter 10, Nest Egg Care (NEC). We have MORE THAN ENOUGH portfolio value needed to support our desired spending for the rest of our lives. You may be Happy Campers now or maybe you will be in the future. In this post I recommend that you do not hold onto your MORE THAN ENOUGH for the rest of your lives, and I recommend how I think it should be invested.

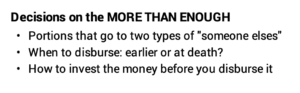

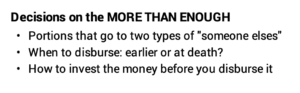

Here are the decisions . . .

1) What portion of MORE THAN ENOUGH should go to charities you like and what portion should go to your heirs? Patti and I have earmarked some for charities and some for heirs.

2) When will you disburse to them? Patti and I decided we’ll disburse our current MORE THAN ENOUGH over the next three to five years. Odds are that in five years we’ll calculate to another MORE THAN ENOUGH amount that we can donate or give.

3) How do you invest? The MORE THAN ENOUGH that you designate for heirs has to be invested 100% in stocks. I decided the MORE THAN ENOUGH that we designate for charities should be invested as 70% stocks and 30% bonds.

== The last several weeks ==

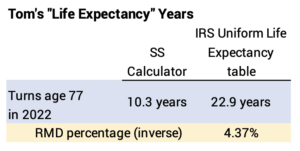

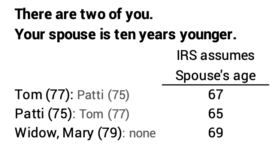

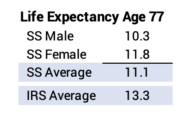

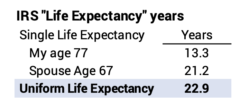

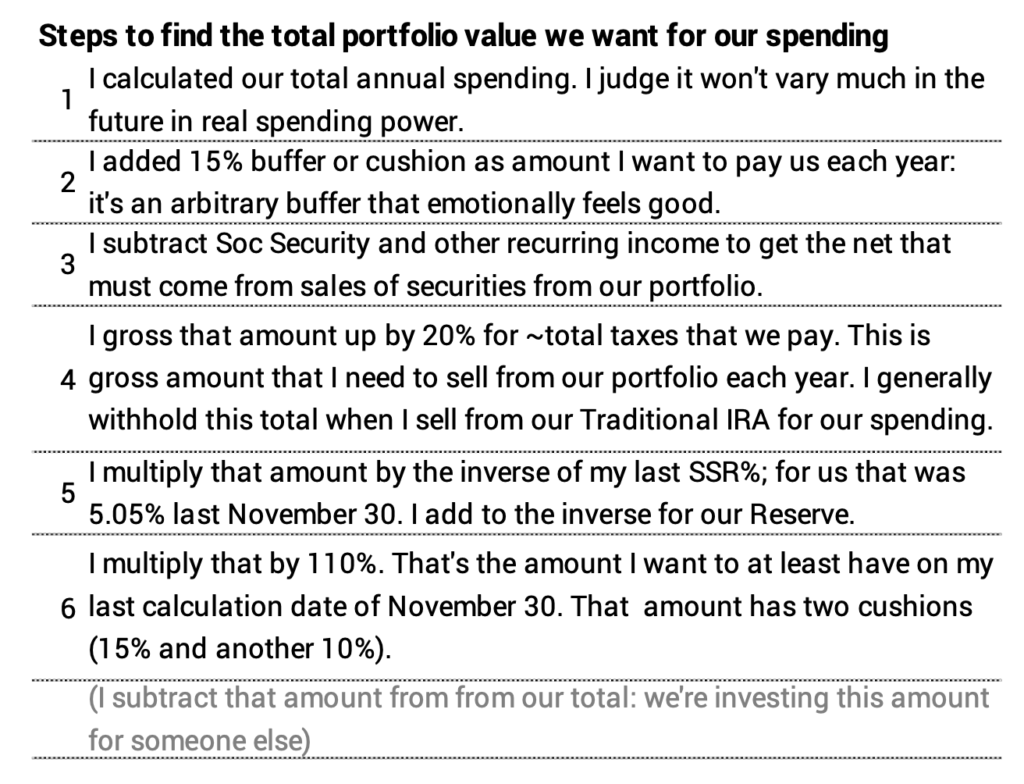

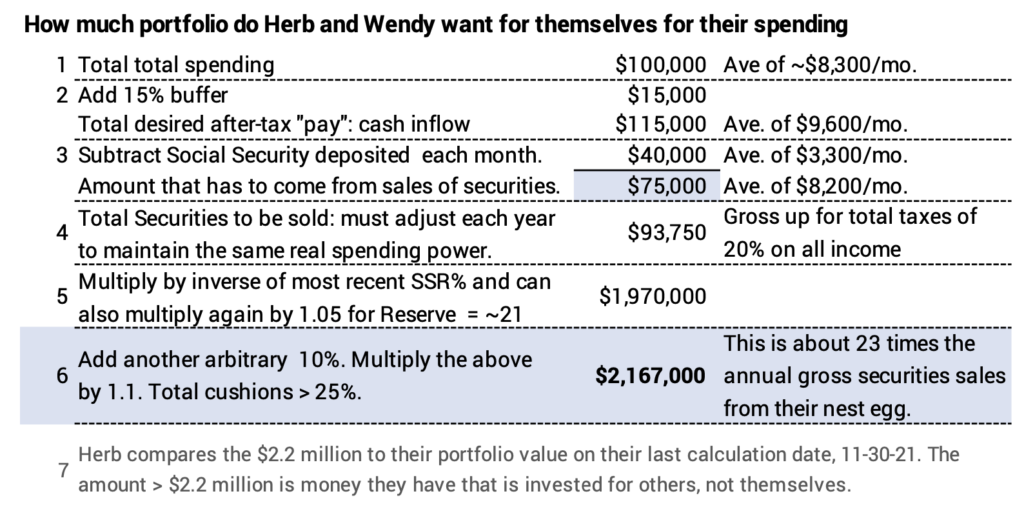

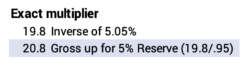

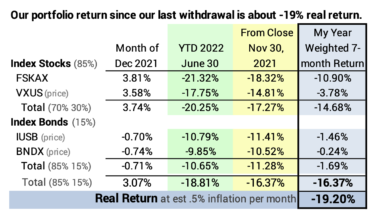

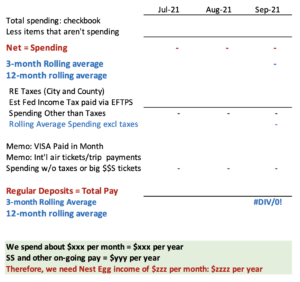

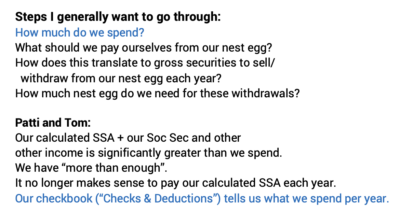

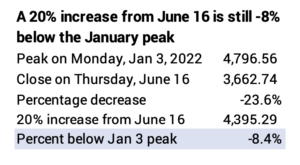

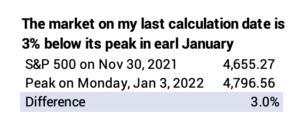

I figured out how much Patti and I spend in a year. I judged it won’t increase significantly in inflation-adjusted dollars for the rest of our lives. I calculated how much we need in portfolio value – ENOUGH for the rest of our lives – basically by using the inverse of our most recent Safe Spending Rate (SSR%. See Chapters 2 and 10, NEC). (I added in two cushions to the calculation.) The total we had on our last calculation date – last November 30 – was greater than ENOUGH. That “excess” is the MORE THAN ENOUGH that I address in this post.

== Where is the MORE THAN ENOUGH? ==

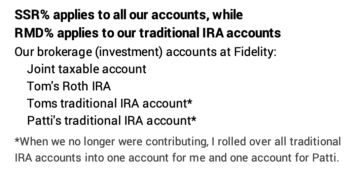

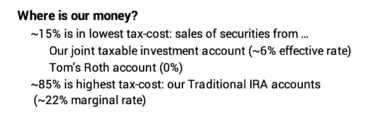

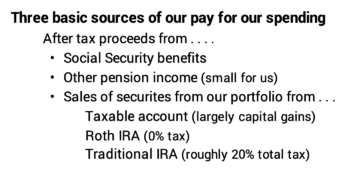

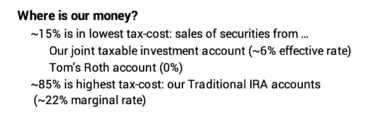

The MORE THAN ENOUGH for Patti and me sits in our Traditional IRAs. NONE of it sits in the 15% of our total that is in our taxable investment account or in my Roth IRA; the money in these two are low-tax sources for our spending in our lifetimes: those are the prime sources I tap for our spending after we’ve made our RMD distributions.

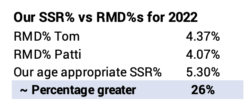

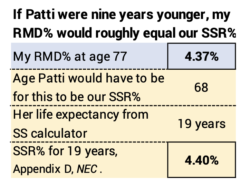

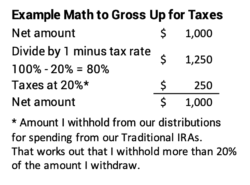

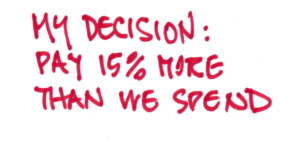

I’m very careful about using our low-tax-cost sources for our spending. Our SSR% is always greater than our RMD%; our SSA is always greater than our RMD. (SSA = Safe Spending Amount; see Chapter 2, NEC.) Each December I sell securities for our spending for the upcoming year from our taxable account, and I primarily sell from my smaller Roth account if it helps to avoid higher Medicare premiums.

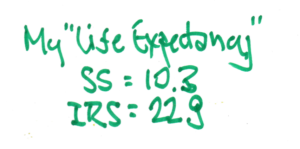

Since our SSR% is always greater our RMD%, I proportionately sell more securities from my low tax-cost sources. Over time, our low-tax-cost sources are a shrinking percentage of our total. That pattern will continue as I work to minimize the taxes that Patti and I pay in our lifetimes. If we live long enough, those two low-cost sourcesn, now at 15% of our total, could get close to 0% of our total. All of our spending then will be from sales of securities from our traditional IRAs; our total tax rate will be higher then, but I’m thinking that’s when we’ll be in our 90s and our spending needs may be far less – knock on wood that we are still around and healthy.

== Who is it for? ==

The MORE THAN ENOUGH isn’t for Patti and me. It’s for someone else. There are two possible “someone elses”: charities or people – our heirs; Patti and I decided on portions for each. Once you’ve decided the MORE THAN ENOUGH for those two, you then have to decide when you give the MORE THAN ENOUGH to them.

== Charities ==

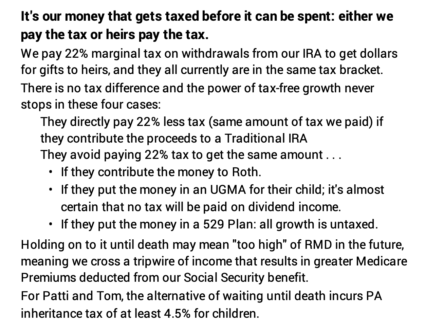

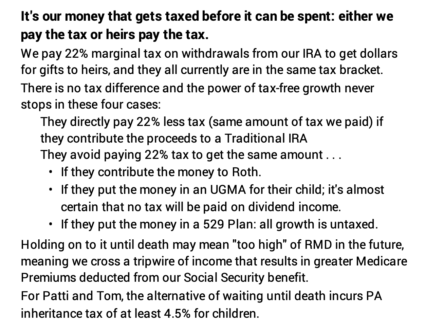

When do we donate the money to charities? I think the decision is clear: donate it now or over several years; Patti and I decided we’d donate the amount over the next three to five years. I see no logic that says you should hold onto this money until death. If you defer these donations, your RMD could grow to the point where you cross income tripwires that result in greater Medicare premiums – the amount deducted from your gross Social Security benefit. That’s not smart.

Always use QCD directly from your Traditional IRAs. You always get the full benefit of tax deductibility of donations, and you avoid any issues of crossing the tripwires that can cost $1,000 or more.

Patti and I spent the time over the last four or five years to pick charities we really like. We focus most of our donations on four. I plan to pay out the allocated MORE THAN ENOUGH over the next three to five years.

How should I invest the portion of the MORE THAN ENOUGH I earmark for charities? I called the four charities. They have their reserves invested, roughly, at 70% stocks and 30% bonds. That’s the way I have invested the money that will flow to them. I don’t have that money sitting in an account identified as “MORE THAN ENOUGH for charities”, so I can’t directly track my percentages, but I will be close. (I could set up an account for that, though.)

== People ==

In general, leaving money in from your traditional IRAs to be disbursed to heirs or others is not the most efficient way to get your money to them. Our wills govern the disbursement of 1) the money in our taxable investment account and 2) the proceeds of the sale of our major non-financial asset, our home. Those are the two best sources of money to leave them because they escape taxes on capital gains. Our will names specific amounts we want to leave to people; the amount adds to a bit less than the net proceeds from the sale of our home. We didn’t include any proceeds from our taxable investment account in that math: again, I don’t view the money in our taxable investment account as something we plan to give them or that we should try to conserve for them.

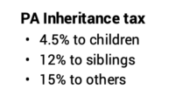

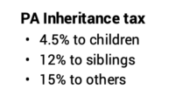

When do we give the money? Patti and I decided to give the MORE THAN ENOUGH allocated to heirs or others while we are alive; we’ll do that over the next five years. It makes no sense to hold on to it. I view that there is no tax penalty by giving it to them now, and, because of the state we live in, Patti and I have a clear tax advantage to give to them now. Our biggest incentive to give now is to avoid Pennsylvania’s inheritance tax.

Even without PA inheritance tax, I see no financial reason to hold on to the MORE THAN ENOUGH for heirs. I see no tax penalty for giving to them now. Our simple assumption is that heirs getting money now will invest the amount we give them to directly be more financially secure. It really makes sense if the money we give them goes from our retirement account to their retirement account, and we’ve encouraged that for all gifts that we’ve made: the tax-free compounding of growth does not stop; it only stops when they sell securities for their spending.

If they spend it, it will be on something that makes them happier now, and we are fine with that. We have NO concerns that they will spend on something that we would judge as irresponsible or frivolous.

Our heirs will primarily invest the gifts we give now in the same way as we invest because I think we’ve educated them on how to be a successful, self-reliant investor: invest solely index funds; 100% stocks to at least ten years before they retire (and none are close to that mark); and the two types of stock funds that Patti and I hold. It will grow by the exact same rate that it would grow if Patti and I held it.

How should I invest the portion of the MORE THAN ENOUGH I earmark for heirs? I have that invested as 100% stocks, which is the way they would invest it if they had it now. Again, I don’t have this amount in an account identified as “MORE THAN ENOUGH for heirs”. (I could set up an account for that, though.)

Conclusion: Patti and I are Happy Campers that I describe in Chapter 10, Nest Egg Care. We have MORE THAN ENOUGH portfolio value than we need for our spending since stock returns for our first eight years significantly increased our annual Safe Spending Amount. If you have MORE THAN ENOUGH – or have MORE in the future – you need to decide who gets the MORE: charities or heirs. One has to decide when to give it to them: Patti and I decided to disburse to both over the next three to five years. Over that period, you have to decide how to invest the MORE THAN ENOUGH. The amount for heirs has to be 100% stocks. Patti and I decided we’d invest the amount for charities at 70% stocks and 30% bonds.