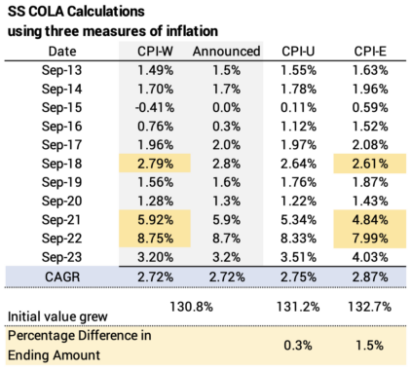

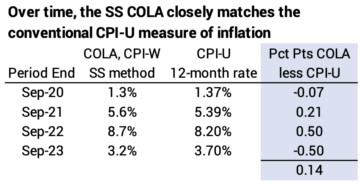

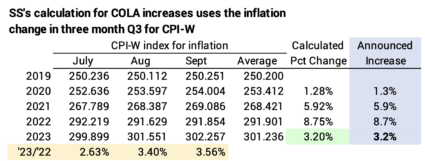

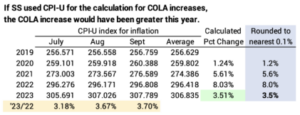

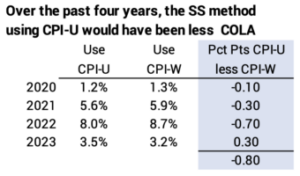

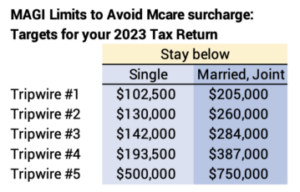

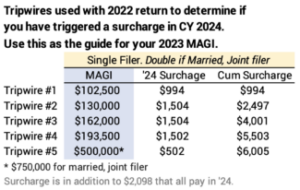

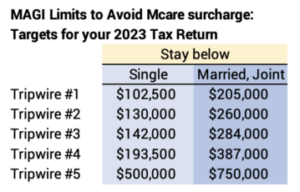

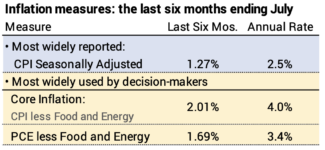

I did my initial plan for our Safe Spending Amount for calendar 2024 the first week of August. I finalize the plan this month, and I can do that now. I have the two items of new information since August: 1) the 3.2% COLA for Social Security and the Medicare Premium tripwires that I want to avoid for our 2023 tax return.

This isn’t new or revised information: it is OBVIOUS that Patti and I – you, too – adjust last year’s Safe Spending Amount (SSA; see Chapter 2, Nest Egg Care [NEC]) for 3.2% inflation. We are FAR AWAY from being able to calculate to a real increase for the upcoming year. Armed with this information, I know how much securities I need to sell in a few weeks to get our 2024 spending into cash and where to sell for lowest taxes.

Details:

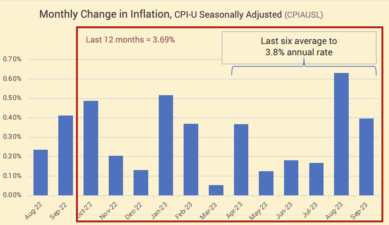

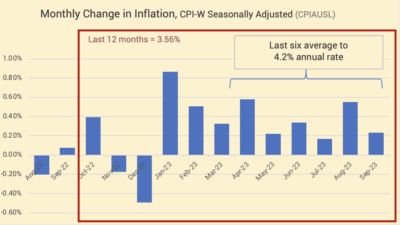

I keep track of the progress of our portfolio return throughout the year. I get the return data for our four funds from Morningstar. The last two months have been stinkers. My chart for the first 11 months of my 12-month year shows about -2% real return. That’s on top of the -18.4% real return for our portfolio last year.

== If we just thought about this year ==

We clearly won’t have the returns over the last year to calculate to a real increase in our SSA. It will simply adjust for inflation. Even though the first days of November have been terrific, I can conceive of the results by the end of November changing this basic story if I only had this year to consider.

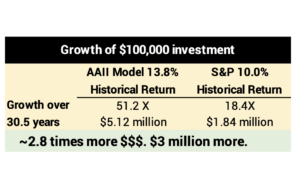

To earn a real increase in our SSA (I’m ignoring the fact that our Safe Spending Rate [SSR%, also Chapter 2] increases over time.), we need to earn back what we withdrew for spending in the year. Assume I withdraw $45,000 from our portfolio in December for our spending in the upcoming year. If returns that next year are such that I earn back more than $45,000 in real spending power, I am guaranteed to calculate to a greater SSA the next year. If I don’t earn back enough, I can only adjust for inflation – no real increase.

I could state this differently. Assume I withdraw 4.5% as our Safe Spending Rate. If I earn back a shade more than 4.5% real return. If I do that, I am guaranteed to calculate to a real increase in our SSA.

== We also have the prior year to overcome ==

It’s MUCH tougher this year, since we all have to overcome the prior year as well as for the withdrawal last year. Our portfolio declined by -18.4% real return last year. Our withdrawal stayed the same in real spending power. That worked out of 6.5% of our starting portfolio value. We would need for this year 32% real portfolio return to earn back the amount to get to our prior peak portfolio value in November 2021.

We all still have BIG HILL to climb to get back on track to see a real increase in our SSA.

== Where to sell to get our SSA into cash ==

I can decide where I will get the cash for our SSA this coming year.

$SSA is always greater than $RMD, so I always play with our tax return to decide where I will sell the added amount I need for our SSA that results in the lowest taxes. That’s a simple task if I just think about this year, but it is more complex if I think about taxes over time, especially when just one of us is alive.

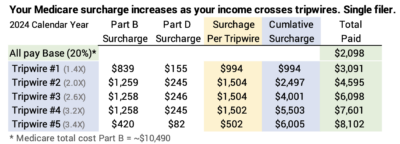

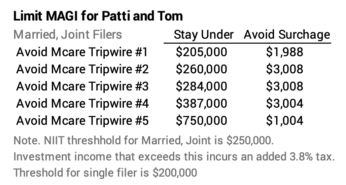

My tax planning for this year is fairly simple: our AGI – Adjusted Gross Income – will not be that close to a Medicare tripwire. I don’t need to jiggle – consider using my Roth – to get our cash to avoid a Medicare Tripwire. I hoard my Roth to be able to avoid a Medicare tripwire, and I don’t have to use it this year.

Overall, our taxes for 2023 will be lower than in 2022 because our RMD is less for 2023 than it was for 2022. This year I’m getting a greater portion of our SSA from sales of taxable securities that have a lower tax bite.

Conclusion: I finalize my tax plan for each year in November. It will be very similar to my first draft that I prepared the first week of August, but now I have the final details. Our SSA gross sales of securities that I’ll essentially withdraw from our portfolio is last year’s SSA + 3.2% for inflation. RMD is a significant part, but not all our SSA. I’ll sell the balance I need to add to our SSA from our taxable account. I can project our AGI and know that we won’t be close to a Medicare tripwire that we could otherwise avoid.