We retirees with Traditional IRA accounts will record increasing taxable income over time. That’s due to RMD, a big component of taxable income for those over age 70½. At expected returns for stocks and bonds, your taxable ordinary income will DOUBLE in real terms over your lifetime. It will more than double if returns are better than expected or if you (ideally) live well beyond your life expectancy. This post explains why your RMD will double and describes what you do if you that would be a concern.

My quick summary: I don’t think this is a big concern. We’ll have more money and more reported income, but very few of us will be pushed into a marginal tax bracket that we would be passionate about avoiding.

I previously posted on this topic and cited how this doubling could push you to a tax bracket that would be painful. But after working through two examples in this post, I think the doubling of RMD is going to be a big concern only for the rarified few who have an UNUSUALLY large IRA. They may face a step-up in marginal tax rate that they would want to avoid by converting big $$$ of Traditional IRA to Roth.

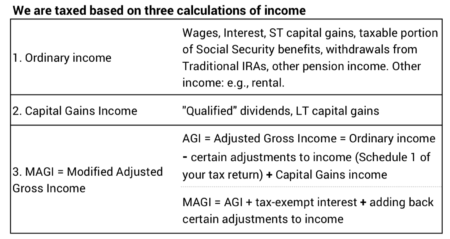

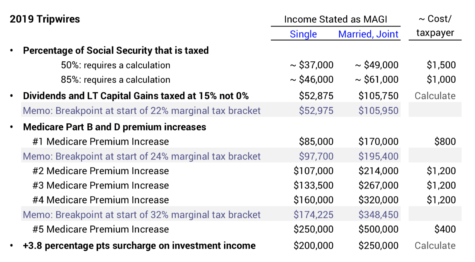

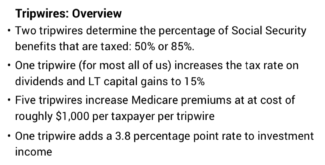

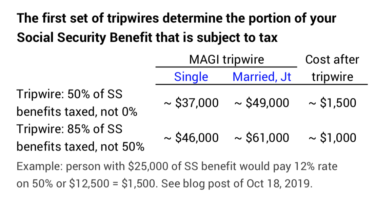

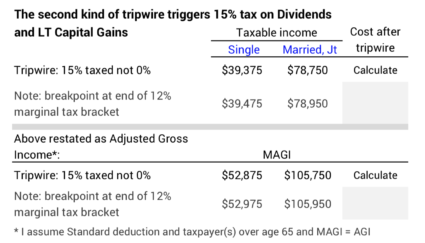

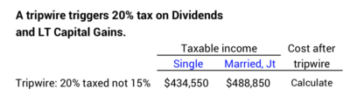

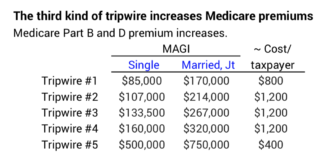

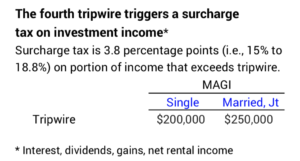

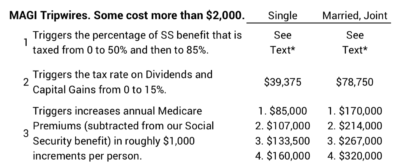

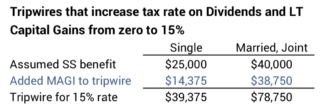

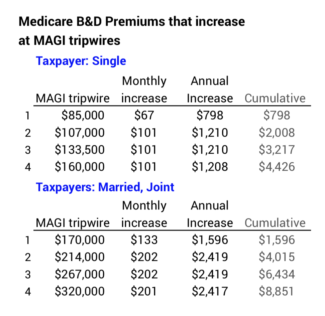

You still may want to convert some Traditional to Roth – I now think it’s more important to have that flexibility to avoid the tripwires of income that result in higher Medicare premiums – but it’s just not that big of an advantage for ordinary taxes. Let’s review and refresh on this.

== The benefit of converting Traditional to Roth ==

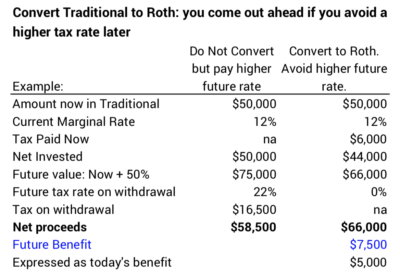

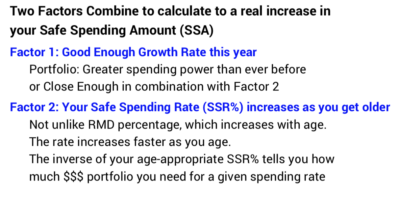

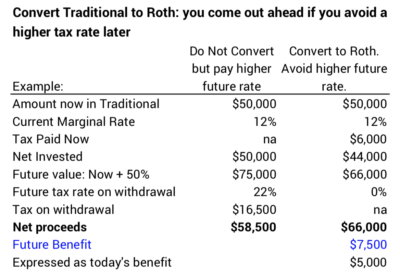

You accomplish two things when you convert $$$ Traditional IRA to Roth. 1) You are lowering the amount subject to future RMD. 2) You have locked in the current tax rate that you pay when you convert; you are ahead of the game when you withdraw from Roth for your spending and otherwise avoid a higher marginal tax.

You never really lose when you convert Traditional to Roth. You never stop the advantage of tax-free growth in your IRA. If your future tax rate is the same as today, Traditional and Roth result in same net benefit to you. I don’t see how it is possible that you’ll withdraw for spending when you are in a lower marginal tax bracket than you are in now – that’s the only case where you lose when you convert Traditional to Roth.

The math of converting makes sense. Our intuition and emotion fights the math: we have a hard time deciding that it makes sense to pay taxes now to avoid taxes in the future.

== Two marginal tax brackets we’d like to avoid ==

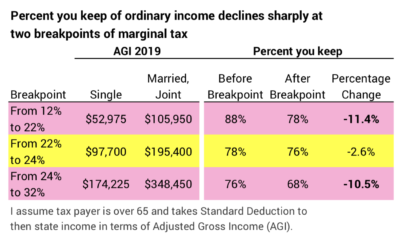

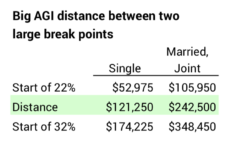

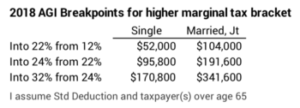

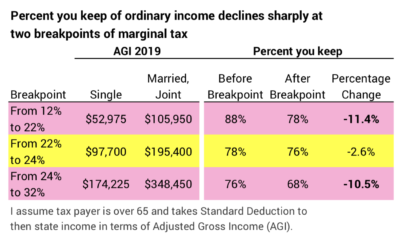

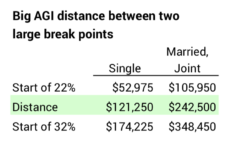

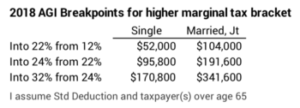

We retirees don’t want to waste money. We waste money if we pay taxes at a marginal tax rate that we possibly could otherwise avoid. We get to keep about 10% less of the income that’s taxed after these two breakpoints – $1,000 less per $10,000 of taxable income: 1) the step from 12% to 22% marginal tax bracket and 2) the step from 24% to 32% marginal tax bracket.

Folks facing these two breakpoints are obviously at very different levels of taxable income: roughly $240,000 difference in taxable income for married joint filers.

The step between the two – from 22% to 24% is one-fifth the damage of the other two. It costs us about $200 per $10,000 for the incremental income that falls into the 24% bracket. I would not be exercised about this if I were in this big range of income. I basically look at that long run of +$240,000 taxable income (married, joint) between the two big breakpoints as one very big tax bracket.

== Might you cross into a painful bracket? ==

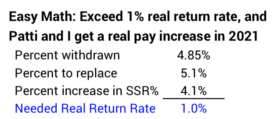

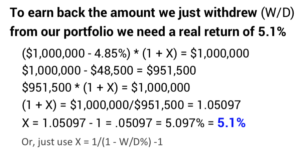

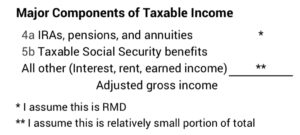

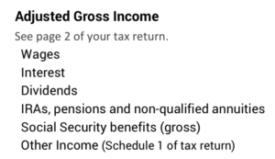

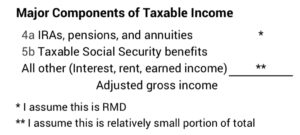

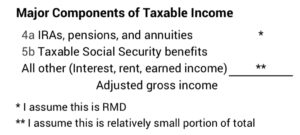

You need a simple forecast of future income to answer this question. I think the math is simple but it requires that we think in real, inflation-adjusted returns. I’m assuming you – like Patti and me – have (or will have when you are retired) two big components of ordinary income and All Other is generally in the noise level and won’t change in real terms over time. It’s simpler if we think about just three factors in this math: Social Security income, IRA income (RMD), and the marginal tax breakpoints.

== Two of the three never budge ==

1. Social Security benefits stay at the same real spending power. [Social Security announced 1.6% Cost of Living Adjustment for 2020 in October.]

2. The breakpoints for marginal taxes under current tax law also stay the same. [The IRS recently announced 2020 breakpoints for marginal taxes that also adjusted for 1.6% inflation.]

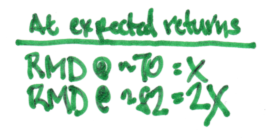

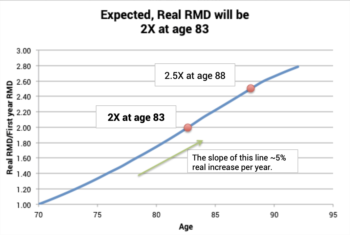

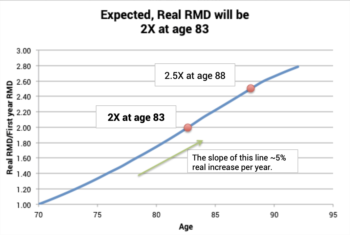

== Your RMD will double ==

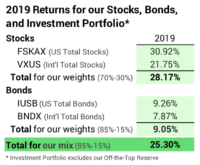

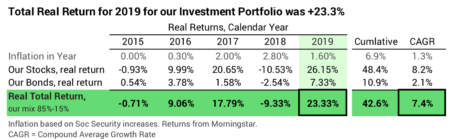

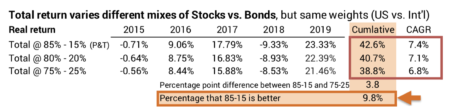

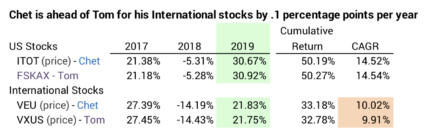

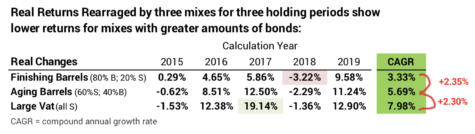

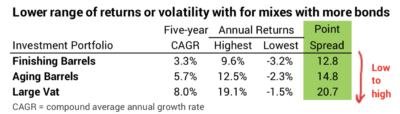

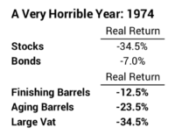

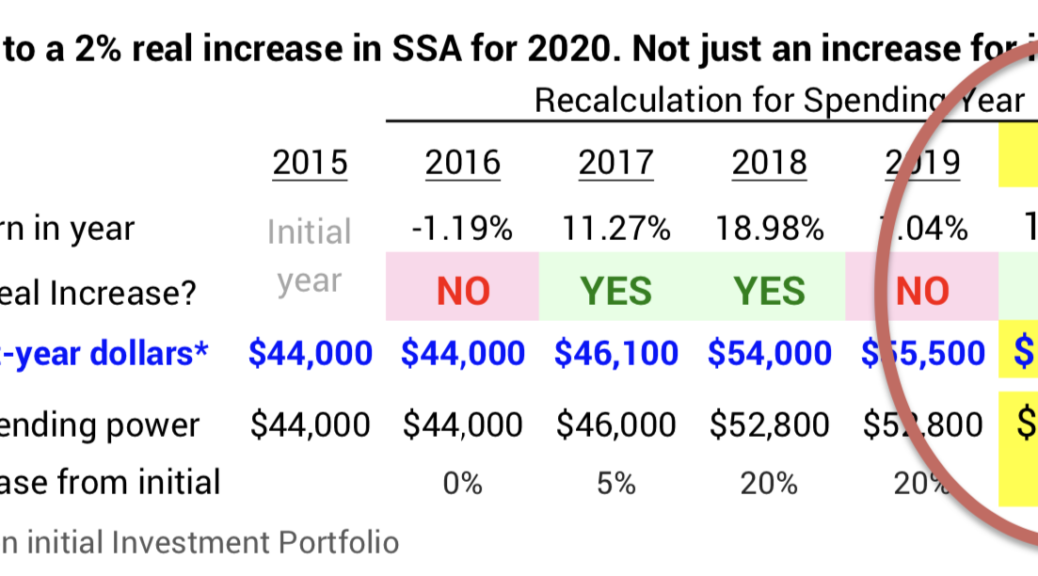

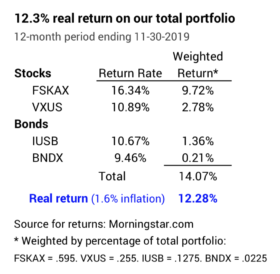

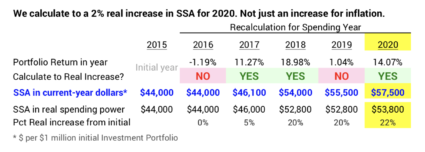

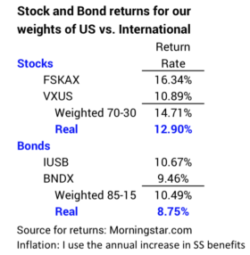

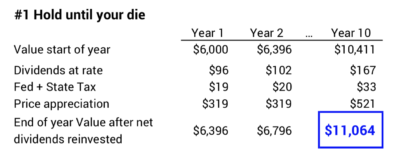

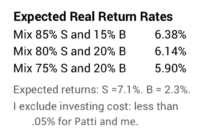

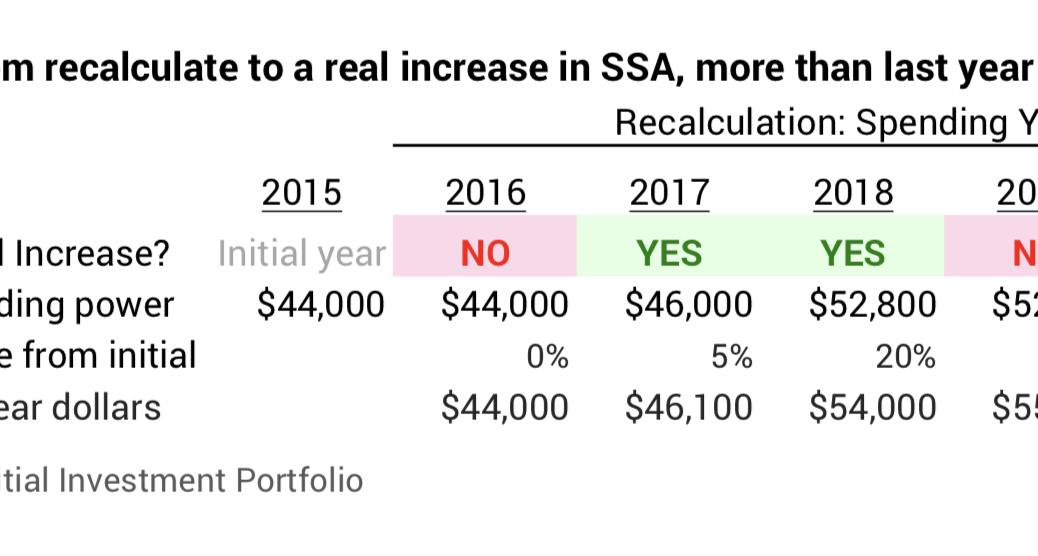

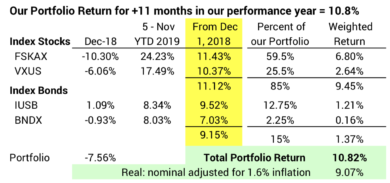

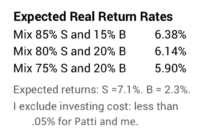

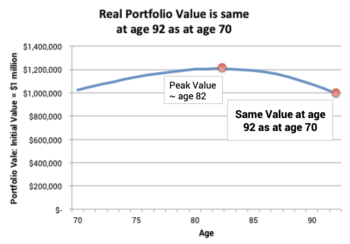

By your early 80s, your expected, real RMD will most likely DOUBLE the amount you will take in your first year. I went into some detail in the post I cited above. For the graph below, I used real expected returns for stocks (7.1%) and bonds (2.3%) and the mix of stocks and bonds that Patti and I selected: 85% stocks. A graph of results using a mix of 75% would look similar.

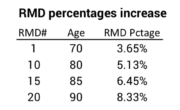

RMD increases in real terms from the combination of two factors: increasing RMD percentage and real increases in portfolio value.

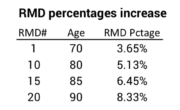

• My first year RMD percentage was 3.65%. When I am 80 it will be about 50% greater (5.35%). The RMD percentage will be more than double when (if!) I am 87.

• IRA portfolios will continue to grow at expected return rates because the return rate is greater than the RMD percentage for many years. The expected return rate on our portfolio is 6.38%. My RMD percentage first exceeds 6.38% at age 85.

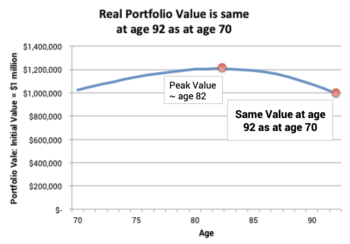

Real IRA portfolio value peaks in my early 80s and then declines. I have the same real portfolio value at age 92 as at age 70. A graph that uses a lower portfolio expected return rate – a lower mix of stocks than Patti and I have – looks similar.

== Use your 2018 tax return to get a snapshot ==

You want to know how much of your future income might be in a tax bracket that you would otherwise like to avoid.

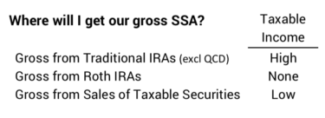

1. Pull out your 2018 tax return and simplify the entries to three. The first two items of ordinary income – IRAs and Social Security – are far bigger than All Other ordinary income for Patti and me. Remember that dividends and long-term capital gains income are taxed differently – 15% rate for Patti and me.

I assume you (or you and your spouse) received Social Security benefits in 2018, so that won’t change in real terms over time. If you are not subject to RMD, you’ll have to estimate your first year RMD. You need to estimate your IRA value for your first RMD. I’d use your current value and its expected return rate from now until then: ~6% rate. I’d use 3.7% of that estimate for your first RMD. Those two assumptions are close enough for this task.

2. Understand the tax bracket you are in and how close you are to the next marginal tax bracket.

3. Recast your return for what it will look like in the future. Double your first-year RMD, but don’t change the other two. (If you have already taken several RMDs, eyeball on the graph where you are to judge the expected increase: it will be less than double.) You have a new total. Now calculate how much of your income is taxed in the bracket that you would like to avoid. Calculate 10% of that: that’s the potential you could save in a future year if you could avoid that tax bracket. Is this an amount that concerns you?

My guess is that you will fall into one of three categories.

1. You are in a 12% bracket now and cross into a 22% bracket, but the potential dollar impact is not huge, and you just don’t have that much capacity to save on taxes: you have too little capacity to convert Traditional to IRA. This is Case 1 below.

2. You are near or in the 22% or 24% tax bracket and are miles away from the 32% tax bracket. It looks like you’ll never hit the 32% bracket. This is Case 2 below.

3. You are one of the fortunate few with a VERY LARGE Traditional IRA and can see you will have a significant amount taxed at 32%. You do have capacity to convert – you are not near 32% now, and the savings in total tax dollars saved is significant. You are lucky to have this problem!

== Two Cases ==

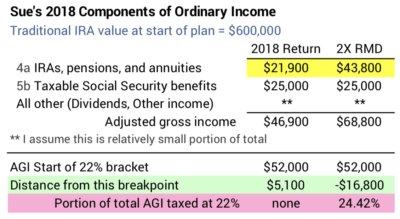

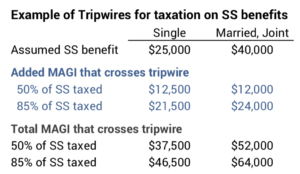

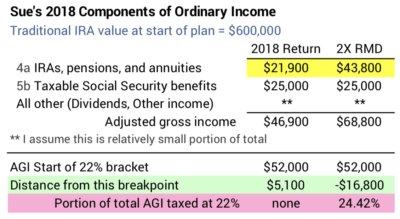

Case 1: Sue is single. She recorded her first RMD in 2018 on $600,000 in her IRA as of 12-31-2017. She is in the 12% bracket and not far from 22% tax bracket. She can see that when RMD doubles almost $17,000 of her total ordinary income is taxed at the 22% rate. That’s about $1,700 more in tax than if she stayed in the 12% bracket. She’d sure like to keep that $1,700 for herself.

What can she do? Sue now is $5,000 from the 22% tax bracket. That’s her capacity to convert Traditional to Roth this year. That’s not a lot of capacity, but each time sheet converts she gets to keep 11% more of each amount she converts – that’s the effect of paying 10% now to avoid 22% later.

The math says Sue will save $550 if she converts $5,000 from Traditional to Roth, but she has to pay added tax of $600 (12% times $5,000) this year. The computational, logical part of her brain should decide this is the right thing to do. But the intuitive, emotional part of Sue’s brain is going push back – hard – on this. My guess is Sue won’t convert. It’s too tough to decide to pay more more tax now to avoid paying much less tax later.

========

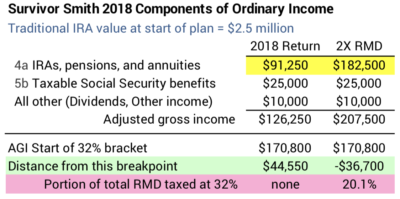

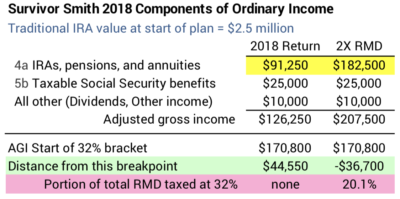

Case 2: The Smiths (Married, Joint filers) also both recorded their first RMDs in 2018 on a total of $2.5 million in their IRAs as of 12-31-2017. They are in the 22% bracket and some distance from the 24% bracket. They can see that when RMD doubles they’ll cross into the 24% bracket, but not by much. They would still be far from the start of 32% bracket. This is a weak case to convert Traditional to Roth as long as both Smiths are alive.

This is very different when one of the Smiths dies, because for a single filer the 32% tax bracket starts at half the taxable income for married, joint filer. In this example I lower Social Security benefits and keep all other income the same. Now 20% of RMD is taxed at the 32% bracket. The surviving Smith and heirs would be better off to pay more tax in the 22% and 24% tax bracket – converting Traditional to Roth – to avoid the big bite at the 32% bracket later.

Conclusion: At expected return rates, your RMD will double in real terms over your lifetime. This will push you toward a higher marginal tax bracket. You’d like to avoid two breakpoints of marginal tax rates in our current tax law: the breakpoint from 12% to 22% and the breakpoint from 24% to 32%. This posts suggests that very few of us will be pushed toward those breakpoints and also have capacity to avoid them. Married couples need to look harder at this issue, since the breakpoints high marginal tax rates are half that for married, joint files. You lock in your current tax bracket by converting Traditional IRA to Roth.