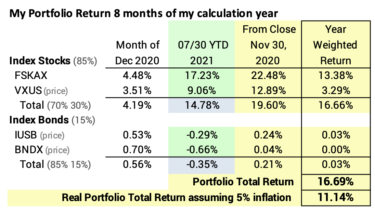

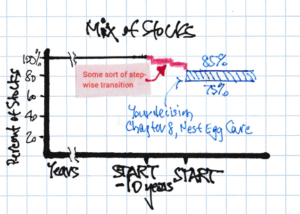

When Patti and I officially started our Nest Egg Care retirement plan in December 2014, I had no Roth IRA. All our retirement accounts were Traditional IRA, and most of our money was in retirement accounts. I posted here and here about the importance of Roth IRAs. I converted some of my Traditional IRA to Roth in 2018, 2019, and 2020. Our total in Roth is small relative to the total if our retirement accounts – less than 5% of our total – but I see Roth as a valuable tool to avoid taxes that I would otherwise pay. I described my thinking on using Roth just in May, but this post links more clearly to my tax planning of three weeks ago: it’s a clearer description of when to withdraw from Roth to get most bang for your buck – more tax dollars saved relative to the taxes you paid when you contributed to your Roth.

== Review: why convert Traditional to Roth? ==

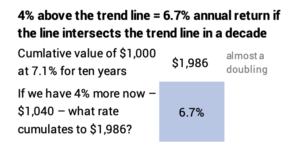

You incur no cost when you convert from Traditional IRA to Roth – Traditional or Roth result in the exact same after-tax dollars to spend in the future. Yes, you pay taxes at your marginal rate in the year you convert, but you are avoiding the same (or more) marginal taxes in a future year. Both have the same benefit of tax-free growth, and if you use Roth to save the same marginal taxes that you paid when you contribute, you wind up with the same after tax proceeds.

Roth gives you the opportunity to avoid higher marginal taxes that you would pay in the future had you not converted. You can get more than you paid.

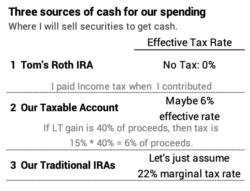

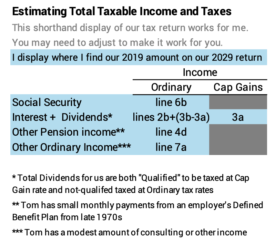

Example: each year I have to pick my sources for our Safe Spending Amount (SSA; Chapter 2, Nest Egg Care). I described this in the post three weeks ago. Our age-appropriate Safe Spending Rate (SSR%, also Chapter 2) is always greater than our RMD percentage. (Patti and are both subject to RMD.) Therefore, our SSA is always greater than RMD. Each year I withdraw more for our spending from our Traditional IRAs than our RMD total.

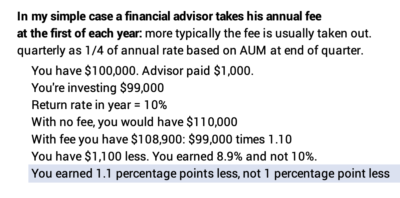

Let’s assume I paid 22% marginal tax on the amounts converted. I breakeven – I wind up with the SAME after-tax dollars to spend – if I use Roth to replace withdrawals from our traditional IRAs that would be taxed at 22%.

I come out AHEAD with Roth – I gain after-tax dollars to spend – if I can use my Roth for spending and avoid a tax that I would pay if I used another source for our spending. I potentially avoid two taxes by planning out our Adjusted Gross Income and taxable ordinary income, like I did three weeks ago.

• I gain after tax dollars if I can use Roth to get under a tripwire of total income – Adjusted Gross Income – that triggers an increase in Medicare Premiums. (I consider premium increases as added taxes.) This is clearly the most important use of Roth: I can save an incremental $1,700 by using, as an example, $10,000 of Roth: I get an immediate 17% incremental return.

Our Medicare Premiums are deducted from our Social Security benefits. $1 of income above the first tripwire costs us $1,700 and others tripwires cost much more. I need to estimate how close I am to a tripwire every year. Because the tripwires don’t automatically adjust with inflation; I’m being pushed closer to a tripwire with no real increase in taxable income. This is the first thing I looked at when I did my draft tax plan for 2021 three weeks ago. The tripwires are spaced about every $50,000 of total income for married, joint filers and about every $25,000 for single filers. This post shows the Medicare tripwires for 2021.

• I come out AHEAD when I use Roth if we (or Patti or I) would ever be in the 24% marginal tax bracket. I paid 22% marginal tax, and I come out ahead if I can avoid falling into the 24% marginal tax bracket. This is an incremental 2% benefit, but I should take advantage of it assuming I will still have enough remaining to avoid a tripwire for increased Medicare premiums.

== Roth is more important when there is one of us ==

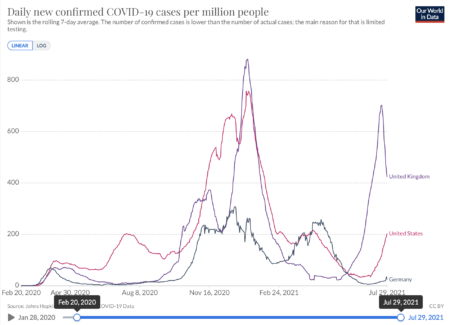

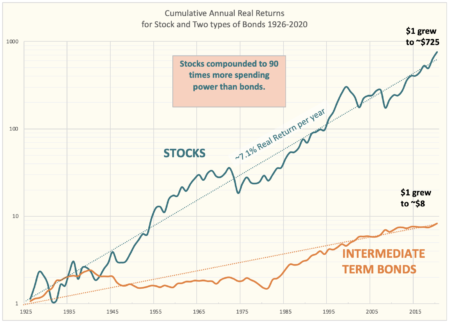

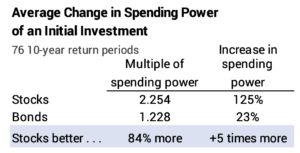

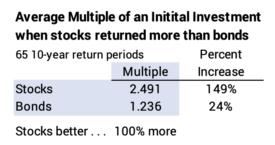

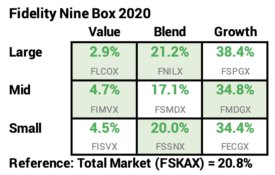

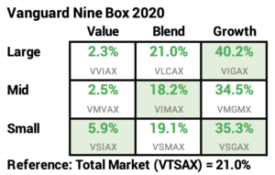

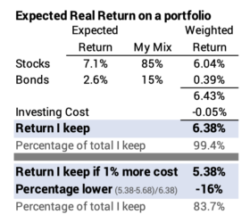

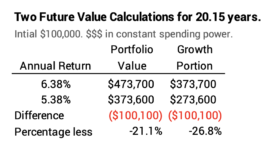

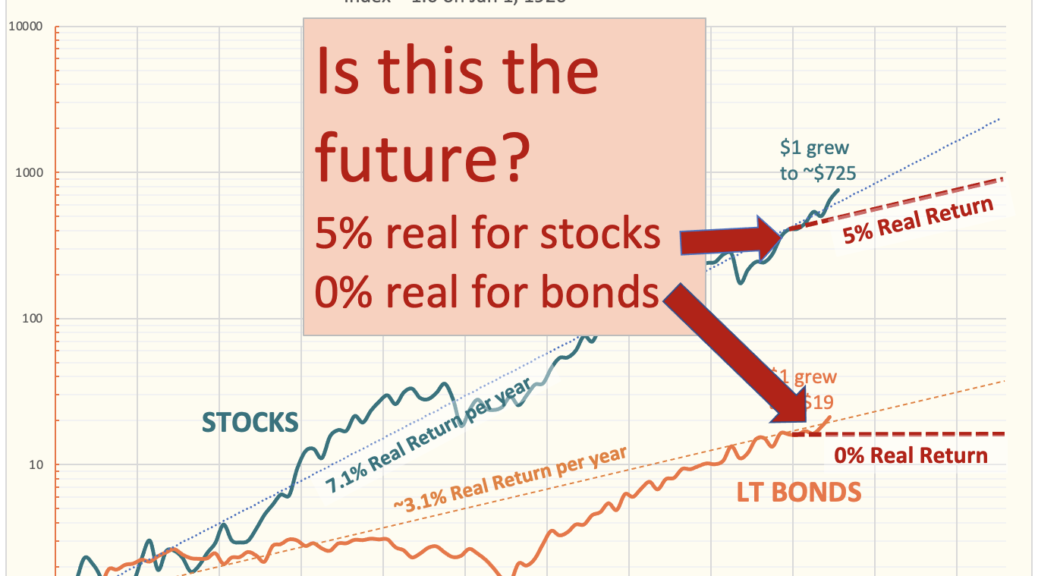

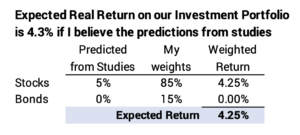

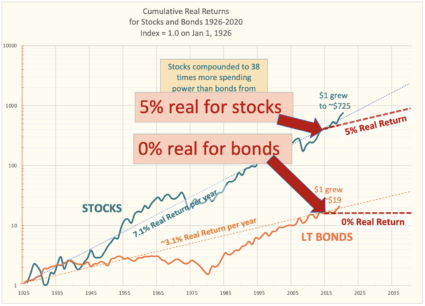

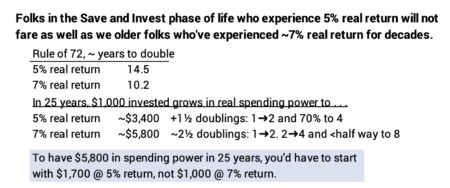

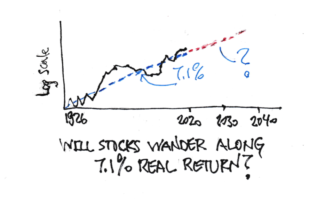

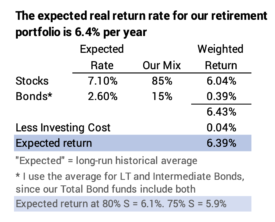

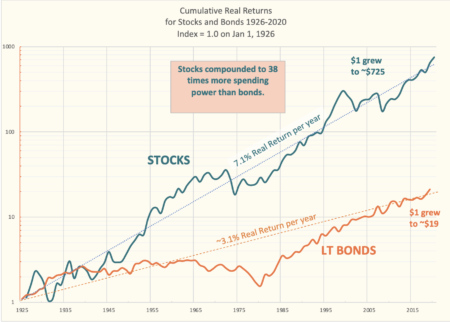

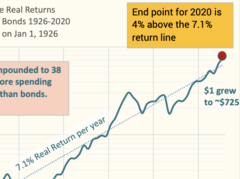

Taxes change when it’s just a single taxpayer and no longer joint, married taxpayers. It’s highly probable that the taxable income of the survivor of the two of us will crawl into the 24% marginal bracket. And the 32% marginal bracket is not out of the question for some retirees if the survivor lives long enough and if returns for stock and bonds track close to their expected return rates. See here.

Why are taxes higher? The marginal tax brackets for the survivor – single taxpayer – are half that for married, joint filers. Yet, the single tax payer will record the same real increases greater portfolio value as if both were alive; that leads to greater real amount of spending power subject to RMD; and RMD percentages increase with age.

This gets hairy, and each of us needs to figure out if we want to spend the time to keep track of this. I do like to keep track, since I think over time I’ll “make” $1,000s by spending a few hours each year to make best use of my Roth.

== An example ==

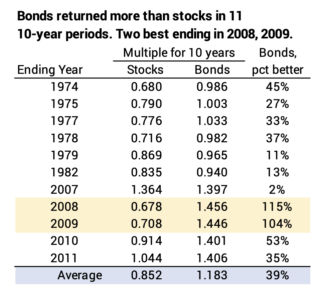

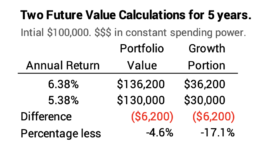

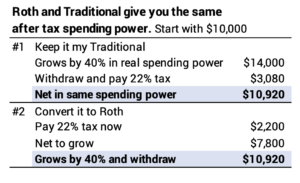

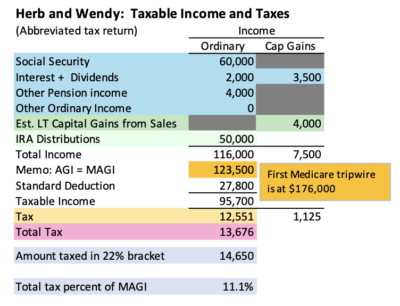

Here’s an example of how taxes and Medicare tripwires can change: assume a couple, Herb and Wendy, have total ordinary taxable income of ~$105,000. They pay total tax of $14,700. About $15,000 of ordinary taxable income is taxed in the marginal 22% bracket. They aren’t close to a Medicare tripwire that would increase the premium.

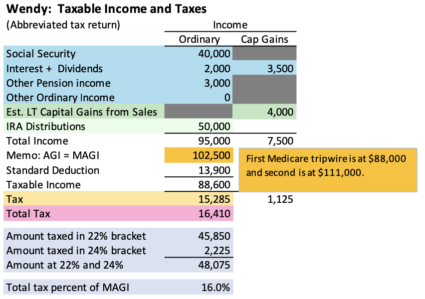

Let’s assume Herb dies. Wendy will have lower total income: she’ll lose the lower Social Security benefit, as an example. She would have about $20,000 less taxable ordinary income in this example, but would pay $16,400 in tax – about 25% more than if Herb was still alive. About $50,000 of income is taxed at the 22% or 24% marginal tax rate. She also would cross a Medicare tripwire that would cost $860.

This PDF shows greater detail than these two images.

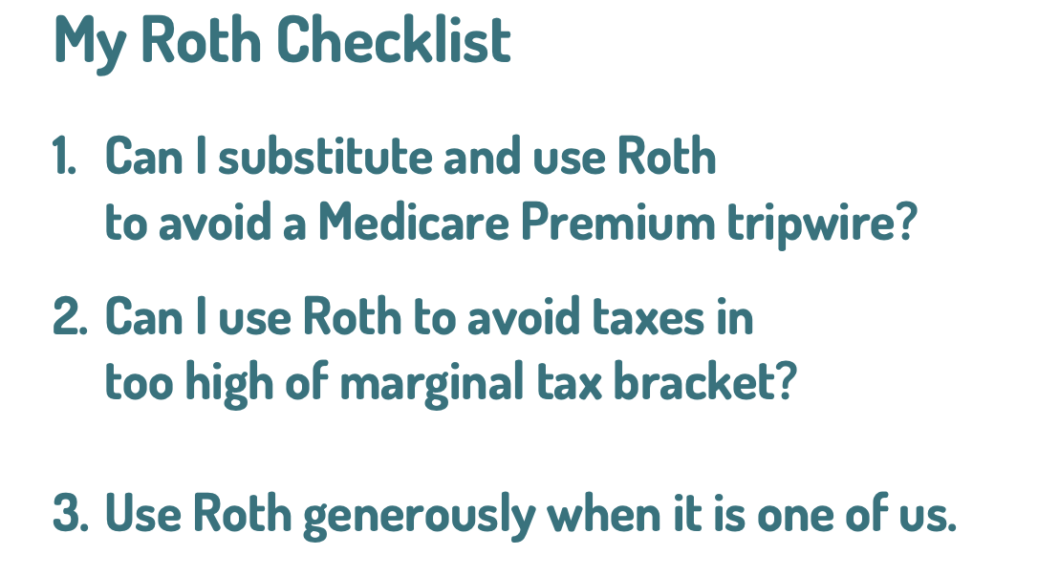

== My annual checklist and story to Patti ==

It’s important to use your Roth wisely. Here is my checklist when I do my draft tax plan each August. I redo this in the first week of December, when I know exactly the tax implications of our SSA for the upcoming year. I will be much closer to our full year tax return. I ask these two questions:

1. Can I substitute Roth for Traditional this tax year to drop our Adjusted Gross Income to avoid a Medicare tripwire?

2. Can I substitute Roth for Traditional this tax year to avoid paying tax in the 24% tax bracket?

My story to Patti is this: after I’ve died, use Roth generously. Try to complete a tax plan (or have someone help) to at least avoid a Medicare tripwire EACH YEAR. Any Roth that you use if you cross into the ≥24% tax bracket is a good use of Roth.

Conclusion: I recommend you convert some Traditional IRA to Roth, being careful not to cross into a higher tax bracket when you convert. Conversion costs you noting in terms of future after-tax dollars to spend. Roth, however, gives you opportunities to avoid future taxes that you do not need to pay. You need to spend some time each year to sort this out, but the two opportunities are to 1) use your Roth for spending and not another source that records taxable income that crosses a tripwire that increases your Medicare Premiums; and 2) it is very likely that the survivor of a couple will be pushed into a higher marginal tax bracket; use Roth generously when that happens.